The Wounds of Language

War leaves wounds on people, land, even language. Yu Miri, winner of the Akutagawa Prize and U.S. National Book Award for Translated Literature, contemplates the impact of the invasion of Ukraine.

Transcript

At the beginning of the invasion,

the Russian army attacked the

Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant.

No one paid any attention then,

but the people in this area

were besieged, psychologically,

and suffered from

hyperventilation and insomnia.

"Yu Miri

Playwright and Novelist

Living in Fukushima

Born in 1968"

I mean, in Fukushima, those who live

near the nuclear power plant know that

they're most vulnerable to emergencies,

be it natural disaster or war.

"Yu moved to Fukushima after the 2011

Great East Japan Earthquake and opened a book cafe"

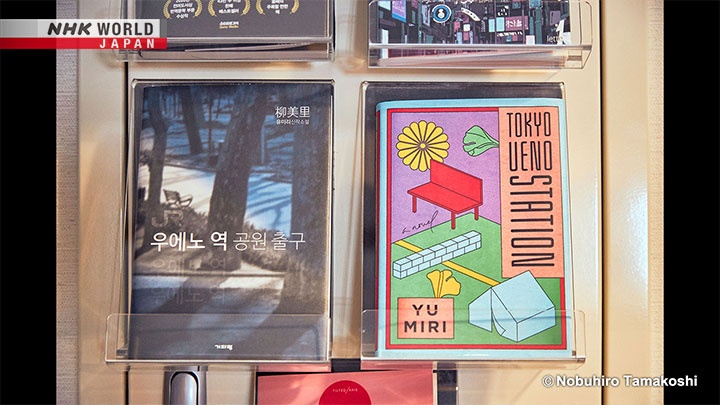

Two different covers,

British and American.

Interesting, aren't they?

"Tokyo Ueno Station (trans. Morgan Giles)

Winner of The National Book Award for

Translated Literature in 2020 (U.S.) "

"A 30-year-old man leaves Fukushima for

Tokyo in 1963, a year before the Tokyo

Olympics, to work in construction"

"He returns home at the age of 60, and in

2000, after the death of his wife, he

arrives in Tokyo once more"

"While searching for 'the way home,'

he spends his nights in Ueno Park, unhoused"

In my thirties, I did overtime every night.

As I walked to the station, I'd be overcome by the waves of salaryman on the way back from work,

and I'd wonder if they had families waiting for them at home,

and on nights after it rained, I walked in my muddy boots over the wet asphalt,

shimmering with reflections of neon signs, and then I could smell the rain-

The calendar separates today from yesterday and tomorrow,

but in life, there is no distinguishing past, present, and future.

We all have an enormity of time, too big for one person to deal with,

and we live, and we die-

"February 24, 2022

Russian invasion of Ukraine"

"What Japanese artists think"

"Yu finds something in common between

Fukushima and Ukraine"

"Yonomori Park

Photo: Yu Miri

Within 7 km from the Fukushima Daiichi

Nuclear Power Plant"

"A month after the nuclear disaster,

Yu visited Fukushima, 300 km north of

her home in Kamakura"

I'd never seen sakura trees

blooming so fully before.

The trees seemed to be straining

under the weight of the blossoms.

I left Kamakura in the morning,

passed the checkpoint, and when

I reached the park, the headlights

of my car pierced the darkness.

Then, many dogs appeared, pets that had

been let loose by the fleeing residents.

They must have thought their owners

had come back for them.

Among the images of

the Russian invasion, I saw

debris-covered cats and dogs wandering

about the shells of bombed-out houses.

That reminded me of Fukushima

soon after the disaster.

"As of July 2022, entry restrictions for the

Yonomori Park area are relaxed"

That phonebook's out of date, surely.

It's not working.

Normally, there'd be signs of life

as you pass by these houses.

You might hear the TV, or smell

the aroma of miso soup or pasta sauce.

It's life that marks the flow of time.

So in that sense,

time has stopped here.

That's what happens when people are

forced to flee, abandoning connections,

whether it's earthquakes, tsunamis,

nuclear plant accidents or war.

"Yu moved to Odaka, 16 km from the nuclear plant,"

"and opened a bookstore in 2018, adding a cafe in 2020"

"Her motivation came from hearing the

stories of survivors, --the interviews she did

for a local emergency radio station"

I felt I wasn't qualified to give even

a sympathetic response to their accounts

of their extreme experiences,

of time itself overwhelming them.

Someone who used to live with

his son's family said that

they would never come back

to a home near the nuclear plant.

Now he's living alone, feeling desperate,

as he overlooks a swing that he made

for his grandchild in the garden.

Others are in despair over the

utterly changed state of the town.

Their agonies come from everyday life.

I felt that I can't even listen to them

unless I live that same life,

that I'd be able to give my response

only after feeling the same pain.

So that's why I'm here.

"She's preparing yet another supportive

space for the locals"

This is going to be a theater.

"Theater & Cinema

La MaMa ODAKA"

There was no cinema between Iwaki

and Sendai since even before the earthquake.

I organized a theater company

when I was eighteen.

I've focused on writing novels for

twenty-five years, but now

I'm getting back into theater.

"Yu is planning to screen films and create

performances with locals"

I got a loan from a bank and

did some crowdfunding,

but it's still not enough.

"She hopes the space will bring comfort to

survivors and vitality to the town's youth"

"Yu was invited to the Lahti International

Writers' Reunion (LIWRE) in 2022"

"LIWRE started in 1963, in the midst of the Cold War,

to bridge the Eastern and Western literary worlds"

"Yu met a Ukrainian and a Russian writer"

I met Iryna Tetera, a Ukrainian writer

from Crimea who speaks Russian.

She said that Russia has been trying

to justify their invasion of Ukraine

as an attempt to save

Russian speakers from persecution,

and that was why she abandoned

the Russian language.

But her parents don't speak Ukrainian,

so there is a rupture in her family.

Her language had been usurped, wounded.

That's how she put it.

I also met Mikhail Durnenkov,

a Russian playwright.

We were asked to read our works

in our native language.

I thought he'd read in Russian,

but he used English instead.

I guess he'd listened

to Iryna Tetera's speech,

and sealed off his Russian.

Both writers have children who will

grow up speaking a different language

from their parents' native tongue.

Language, too, has been

severely wounded in this war.

The wounds could be traumatic

for generations to come.

Although I was born and raised in Japan,

I travel with a Korean passport.

"She has faced difficulty of life

and themed life and death in

her controversial works"

"Ever since I failed to kill myself at fourteen,

I have been keenly aware of the

incomplete life I'm living.

From Jisatsu (Suicide)

Bungeishunju"

When the Korean peninsula was under

Japan's colonial rule, they spoke Japanese

because Korean was forbidden.

Then, during the Korean War,

my parents came to Japan as refugees,

so Japanese is my native language.

My language has a historical scar too.

War damages everything--

people, land, even language.

This war is dragging on,

and so will the postwar recovery.

I wonder what will happen to

the wounded languages then.

Will the wounds heal?

I gathered from their expressions

that both writers had been hurt.

Those who experience linguistic dilemmas

have a heightened sensibility to language,

which isn't a bad thing, I think.

It will shine for us someday

and light the way forward.