Transforming Limitations Into Motivation: Nicolas Huchet / Founder of My Human Kit

We feature an engineer who is changing the world for people with disabilities like himself by making the blueprints of myoelectric prosthetic hands accessible to everybody on the Internet for free.

Transcript

Direct Talk

For the past 10 years,

Nicolas Huchet has been undertaking

an unprecedented "Industrial Revolution"

through his innovative approaches.

His unique destiny begins at the age of 18

when he accidentally lost his right hand.

Using digital Fab Lab technology,

a team of enthusiasts, and a 3D printer,

he manufactures his own prosthesis,

the Bionico Hand.

Through this process, he pioneers

a new concept of creating objects,

unique and accessible to all.

His discovery experiences phenomenal success,

taking him around the world,

and into the spotlight.

Today, I realize that

if I hadn't lost my hand,

I would be less happy.

In the field of prosthetics,

it's an industrial revolution

that blends high-tech and low-tech,

meeting a significant demand.

Immediate sharing of open-source plans

enables rapid evolution

and proposes a new economic model,

paving the way for autonomy.

Nicolas establishes the organization

My Human Kit

and its Humanlab, a participatory Fab Lab

dedicated to disabilities.

Those affected are

at the heart of the projects,

creating social connections through sharing.

Weaving connections worldwide,

Nicolas spreads his message:

transforming limitations into motivation.

At 18, I had been working in

industrial mechanics for two years.

I was employed in a

metallurgy company as a worker

when I had a work-related accident

with a bending press, a hydraulic press.

I had my hand amputated.

A week after the amputation,

I found myself in a rehabilitation center

to learn how to use a myoelectric prosthesis.

It's an electric hand controlled by muscles,

and I was shown a video,

and in reality, the hand did this.

It wasn't that.

It was a difficult moment,

a huge disappointment.

Indeed, the prosthetic provided

by the medical establishment,

shaped like a claw,

hidden beneath a plastic glove,

in fact, has very limited functionalities.

For the following 10 years,

Nicolas lived with these new constraints.

And when newer, more sophisticated

prosthetics finally emerge,

he had a renewed sense of hope.

I contacted the manufacturer in England,

who sent me a quote for about €30,000.

I was very frustrated,

very angry because I didn't have that amount,

and I realized that without money,

you can't do anything.

It was a stark reminder because

I come from a very modest background.

At the same time,

Fab Labs were emerging in France.

This global network, initiated by

the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

comprised digital laboratories offering

free access to 3D printing technologies

and open-source software.

By chance, Nicolas meets

the teams from the Rennes Fab Lab

who take an interest in his disability.

We searched for a hand

and found a robotic hand

in an amateur video

demonstrating its functionality.

There was a man pressing keys on his

computer keyboard, making the hand move.

At that moment, I thought,

"That's it, I'm going to do it."

They made me understand that

if I came to the Fab Lab,

they would help me make the robotic hand.

But in exchange for their help,

I had to share the recipe

for making this bionic hand.

That's when it struck me.

I had something, you know?

It's like, outside,

even if the weather wasn't good,

these grey walls had a different color.

Using open-source plans on the internet,

the project of a robot called InMoov,

and 3D printing technology,

Nicolas begins to envision

a custom-made prosthesis for his hand.

But no one knew if this robotic hand

could become as a prosthesis.

I was the only one who could know.

And that's when I realized that

my disability was actually an expertise.

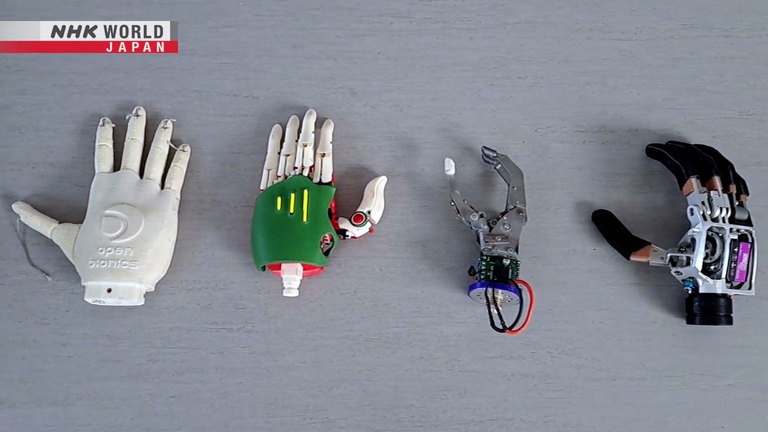

Eventually, he manages to

develop his first robotic hand,

the Bionico Hand,

a so-called myoelectric prosthesis:

it is equipped with sensors

that detect muscle contractions

and transfer these signals to a board, which

in turn activates the fingers of the hand.

Even though the plastic hand is fragile

and struggles to handle certain objects,

it paves a new path and sparks a lot of hope.

This hand was successful because,

actually, for the first time,

I believe in history, there was a prosthesis,

a robotic hand, a bionic hand made by

people who aren't researchers,

created in a garage, with open-source plans

and through collective intelligence.

It was truly to help someone,

and the person using this prosthesis

was the originator of the project.

And that was a first.

It had an amazing impact!

The Bionico Hand receives

significant media attention.

Nicolas is invited to numerous events

worldwide to present his Bionico Hand

but, more importantly,

to generate the idea that one can now

manufacture their own object

with this new industrial revolution.

And gradually, we started asking ourselves

if this wonderful story that happened to me,

with people helping me,

could be repeated with

other types of disabled people.

In 2014, he founds the organization

"My Human Kit,"

dedicated to creating items

for people with disabilities,

and opens the Humanlab, the first

digital Fab Lab dedicated to disability,

allowing people to self-repair.

And the "My Human Kit" means that you,

have the ability to act as a disabled person

who makes your own object.

It could be a prosthesis,

an adapted nail clipper, a yogurt holder—

whatever you want but you participate in it,

and develop your ability to act.

By coming here, there are

kind people willing to help you,

and we put disability

at the center of gravity.

We are received very positively,

very welcomingly,

so it gives us the opportunity

to make friends.

And, how can I say,

to be recognized, actually acknowledged

in our disability, quite simply.

We can be a genuine person.

And it genuinely creates

a social bond in itself.

It means that we have the opportunity

to open up to others

and then to learn by creating all together.

Here, there are tinkerers,

computer scientists, engineers, and more.

All have volunteered to teach them

how to create personalized technical aids.

Most of the people with disabilities

become volunteers themselves,

to help newcomers and

exchange practical advice.

Like every Fab Lab within the Humanlab,

we document all the projects.

This means we write out

the manufacturing steps,

include photos, dimensions,

assembly videos, and more

so that anyone worldwide

can reproduce and improve upon them.

As a result, on our platform, the Wiki Lab,

we have documented over 300 solutions to date,

encompassing both those from My Human Kit

and those contributed by

members of the Humanlab network.

Anyone can access these plans

and go to a Fab Lab nearby

to manufacture the object and

customize it according to their disability.

That's the whole idea - not to patent

but to do the opposite of copyright.

It's copyleft!

We're flipping the idea of a world

where everyone is the same.

Here, no, we exist.

We have our own style of adapted

and unique objects, tailored to our needs.

And in fact, it feeds into

something that's stronger

individual comfort and consumerism.

So, yes, this whole idea of doing it

ourselves is to instill in our minds

and in future mindsets, the fact that

we have the ability to act.

We can have a smartphone and repair it,

have a car and fix it,

a sewing machine and mend it,

a coffee machine and repair it,

instead of replacing it.

And that's what we do with objects

for disabilities and with the prosthesis.

So, we have a manual

that will explain it to us.

We want to offer another solution

that has always existed in times of crisis,

which is mutual aid.

The exchange of open-source data,

mutual aid between those

who are able and those with disabilities,

resourcefulness, and ingenuity

In the field of disability,

it's a new economic model

that blends high-tech and low-tech

to self-produce a dedicated, product

with a response to the growing crisis.

What I want to propose is

an accessible prosthesis

because the reality is that today,

on this planet Earth,

80% of the amputees worldwide

do not have a prosthesis.

That's the reality.

They lack prostheses simply because

they can't afford them!

Even the basic myoelectric prosthesis

is already very challenging

to make widely accepted

and accessible worldwide.

So, that's my mission,

to achieve a generic prosthesis.

Over the course of 10 years,

the Bionico Hand has undergone

numerous stages of research and development.

Today, version 2, crafted from aluminum,

is still undergoing refinement and testing

for manipulation control and precision

to improve its functionality

in everyday situations.

So the hand, it's at this stage,

and it's still not very aesthetically

pleasing, in my opinion.

It's a bit square here, and also it doesn't

move fast enough or grip strongly enough.

I use a mechanical prosthesis

with various adaptations because,

in the summer, it's so hot that

wearing the prosthesis becomes impossible.

Due to sweating, the myoelectric sensors

create interference with electricity,

rendering it nonfunctional.

Therefore, I use a mechanical prosthesis

and attach different tools to it.

For instance, I have a clamp

that I attach to my bike handlebars.

Then I have a knife,

a grater, peelers for carrots,

a knife for tomatoes, and forks, spoons.

I have a clamp to hold a pan,

I have plenty of stuff, actually!

In May 2023,

the My Human Kit team travels to Japan

to participate in the

"Fabrikarium Tokyo" event,

organized with the FabLab Shinagawa.

It's a creative challenge bringing together

Franco-Japanese makers

who will "co-invent"

several prototypes in three days

and present their recent research.

Nicolas presents his GADGET TOOL to Ono San,

who dreams of being a chef in a restaurant.

Thanks to the adapted support

for holding a frying pan,

he is now finally able to make

the famous Japanese omelette!

In fact, in life,

there are things we don't do

because we don't feel capable,

and there are things we really can't do.

Those are the famous limitations.

For example, I have one hand,

and I want to play the drums,

but I can't because it requires two hands.

That's a limitation.

So I rigged up a drumstick for myself,

and now playing the drums is

no longer a limit for me to play.

But when I found myself in front of

an audience with my two drumsticks,

including my adapted one,

I still couldn't play.

It wasn't a limit; it was a barrier.

It was because I didn't feel capable.

I was scared.

But finally I was able to

overcome that barrier.

Nicolas sets the example of

what became the motto of his organization:

Transforming limitations into motivation.

Here, there's room to put disability

in its rightful place in society,

and to stop saying that

we must fight against disability

because we don't fight against disability

like we fight against terrorism or something,

but unfortunately, that's often

how disability is portrayed.

Instead, we turn disability into

a source of creativity, inspiration,

and we put disability

at the heart of projects.

My message is that

"Disability is a source of creativity."