Returning the Benin Bronzes: Nick Merriman / Chief Executive of the Horniman Museum

Britain is re-evaluating its past and that battle is playing out in museums across the country. Nick Merriman explains why the Horniman Museum is returning its entire collection of Benin bronzes to Nigeria.

Transcript

Direct Talk

Britain is re-evaluating its past.

Protesters have even toppled a statue

that was seen to celebrate

its colonial history.

Now that battle is playing out

in museums across the country.

The Horniman Museum in London

has artefacts from around the world -

including a number of ancient bronzes.

These were stolen from Benin City,

now part of Nigeria in West Africa,

and once at the heart of the British Empire.

The Horniman has taken

the controversial decision

to return ownership

of the bronzes to Nigeria.

Its Director, Nick Merriman, is determined

that it should tell a more truthful story

about Britain's imperial past.

He believes this will help broaden

its appeal amongst local residents.

Returning the Benin Bronzes

About five or six years ago, we began

really examining what it means

to be a colonial museum.

The Horniman's collection was

founded and collected

during the heyday of the British Empire,

and it continued up to the 1950s

in terms of major acquisitions.

We also realized from

talking to people who didn't visit us

that there were members

of the black community, for example,

who were very suspicious about the Horniman,

seeing it as a colonial museum

and not for them, didn't speak to them,

because things like the Benin bronzes

were not being addressed.

The case for restitution –

the return of objects

to their countries of origin

is gathering pace

and posing a major challenge to museums

across Europe and America.

The Benin Bronzes, like many of the

historic artefacts that fill western museums,

were acquired by military force

and then sold to collectors

like Frederick Horniman,

a wealthy tea merchant,

who founded the museum in 1901.

In February 1897

because of a political and trade dispute

between the British

and the Oba of Benin City,

a military force went in to

essentially punish the Oba for his

what were perceived to be

trade transgressions

and actually attacking some British forces.

And they destroyed and looted

much of the royal palaces and shrines

and took away what seemed

to be some 10,000 objects.

A lot of them, the so-called bronzes,

are actually made of brass

and they're

cast reliefs, each of them unique, depicting

centuries old members

of the Beninese royal family,

political leaders, military chiefs and so on,

which were attached

to the walls of the palace

along with carved elephant ivory tusks,

domestic items,

bracelets and other items

of jewellery and so on.

These objects were then

sold on the market to museums

and private collectors all around the world.

And it seems that

Frederick Horniman was probably

the first collector in Britain

to acquire material

because he bought some directly

from a man who was involved in the looting

just one month after

the looting actually happened in Nigeria.

Although the Nigerian campaign for the

return of the Benin Bronzes began in the 1960s,

it has been given

added impetus in recent years

by the Black Lives Matter protests.

The Horniman is based in south London,

which has many black citizens

who are descended from

former African and Caribbean colonies.

They want to see the museum

confront its colonial legacy.

Certainly when Nigeria

got independence in 1960,

there have been successive calls

for their return

and it's both physically

returning the history,

but also in a way atoning for some of

what were perceived to be

the crimes of the colonial period.

So they have

a sort of historical and

symbolic significance for

Nigerian communities

both in the UK and in Nigeria itself

and locally to us in the Horniman,

actually our largest minority ethnic group

is British Nigerian people.

So they have a

particularly strong stake in this.

And we have had

a permanent display of Benin material,

which has been a sort of source of interest

and contention ever since it was put up.

So restitution is one part of this,

but a much bigger part, I think

is telling actually

just a wider and historically more

complex and nuanced history

of both how the Horniman was founded

and where the money came from

and also where the collections came from.

And actually when we've started to do that,

it's been really welcomed by our visitors.

In November 2022,

the Horniman became the first British museum

to return ownership of a whole collection,

after its trustees gave the go ahead.

Its 72 Benin Bronzes

were officially returned to

Nigeria's National Commission

for Museums and Monuments.

And in a symbolic act,

a few objects were handed back.

The rest remain on loan

and their long-term fate

has not yet been resolved.

We actually returned ownership in November.

And four of the items that were on display

were physically returned.

The rest are on loan.

We see four gaps

with labels explaining that they've been

returned to the Nigerian colleagues.

And throughout the process,

we've been changing the labels to

reflect, first of all, that the claim had

been made and then the outcome of the claim.

The next big thing is to

work over the next 18 months or so

to redisplay the case completely.

And we're doing that

as a sort of co-curation exercise

with colleagues in Nigeria

and with our local British Nigerian community

saying, what do you think

the story should be?

We're not sure whether

all 72 objects will eventually be returned.

Our colleagues in Nigeria, who we've been

working very closely with, they say

they need to build capacity to

take the various, many objects

that are being offered to them

from institutions around the world.

The Horniman is one of Britain's

most popular small museums,

recently named Art Fund Museum of the Year.

It has over 700,000 visitors a year

and is more than a just a museum.

In in addition to its

wide collection of artefacts

it has an aquarium,

a butterfly house

and extensive gardens.

Its future depends on the museum

continuing to change in response

to the needs of the local community.

It's not mainly a tourist destination.

It's a museum that's held in great affection

over generations of visitors

who come again and again

The thing that I find absolutely wonderful

about being in charge of the Horniman is that

we can have long term relationships

with our visitors.

The best museums are always thinking about

the social impact they can make on how to

inspire people,

give people, improve people's

wellbeing and so on.

And if people are just coming

on a once off visit as a tourist,

that's quite difficult to do.

But because people come again and again here,

I often meet people who say

we come every week to the museum,

which is absolutely incredible.

And I meet people who say, well,

I'm a grandparent now.

My grandparents brought me.

the commonest word people say

in relation to the Horniman

when they speak to me

is that I love the Horniman.

So for a museum to evoke love

is a very rare and precious thing.

Nick Merriman became

Director of the Horniman in 2018.

As a PhD student,

he had stressed the need for Britain

to make its museums relevant to everyone.

His passion for collecting

began at an early age.

I was born in Birmingham.

Both my parents left school at 16 to get jobs.

It wasn't therefore

a very academic household.

We didn't really go to museums and galleries,

my father was interested in history,

but he did it through going

and collecting old stuff, old objects,

which he called antiques,

and my mother called junk

that he sort of filled the house with.

When I was 16, I bought a metal detector

and would go and find things

in the local parks and so on.

Then through a teacher

at my secondary school,

I got on an archaeological dig -

a Roman site at weekends -

and the thrill of uncovering

a piece of pottery

that nobody had seen for

2,000 years that really resonated with me.

I'd always been really interested in

not just what the bit of pottery,

finding the bit of pottery,

but what it meant, the bigger picture,

what this tells us about the past.

Nick Merriman's aim at the Horniman

has been to reinvent

and reinterpret the collection,

and to challenge Eurocentric narratives,

which hide the truth about Britain's

violent conquest of Africa.

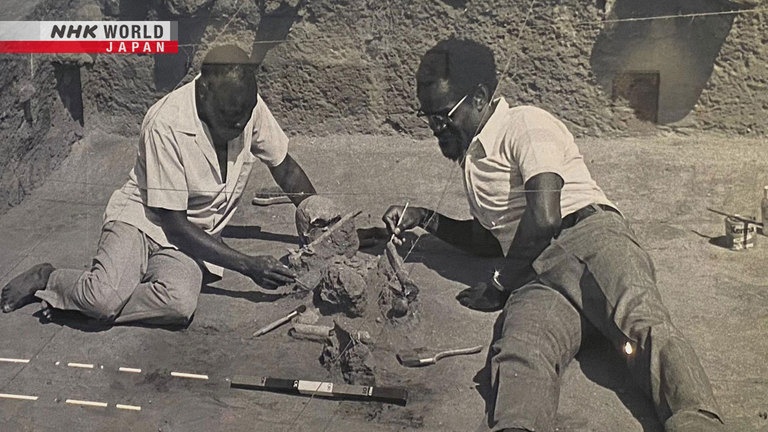

In its current exhibition,

Ode to the Ancestors,

the museum celebrates

the contribution of Kenyan archaeologists

whose names have not been recorded

in the history books.

When you look at the

academic publications from these sites,

it's British white archaeologists

who author the publications,

but the workforce many of whom were

sort of academically trained were Kenyans.

But their names were not

publicized and not known.

So the ancestors are people

who were nameless, who are now

have now been given names and voices

to rebalance the narrative

around who actually did the work

to unearth this archaeology

and tell more about the history of Kenya.

So, again, it's just a wider

and more accurate story

than the one we would have told otherwise.

The French President Emmanuel Macron,

seen here visiting the country of Benin,

has played a leading role

in arguing for the return

of African artefacts

from museums in Europe and America.

He believes that it is wrong

that so much of Africa's cultural heritage

has been removed from the continent.

Restitution claims are all different.

So there's been a lot of publicity

on the Benin material

because nobody disputes

that they were looted.

But that's one specific case.

I think we're going to see more claims.

We are anticipating some claims

for Australian Aboriginal material

that's called secret and sacred material.

Which is material that should only

have been seen by initiated males.

So I think there's a

cluster of cases that are

looting by force or

inappropriate material in UK museums.

We'll probably see a range of those

being addressed in the years to come.

Those are a tiny proportion

of the holdings in UK museums.

People are often worried about,

oh well, if you give stuff back,

the floodgates will open

and British museums will become empty.

The Horniman has about 300,000 objects

and we've agreed to return ownership

of 72 that were clearly stolen.

The largest collection of Benin bronzes

in Britain is held at the British Museum.

And despite growing media attention,

it has so far refused to return them.

The trustee say that the British Museum Act

prevents them from returning any object

in the collection on moral grounds.

My understanding is that

the British Museum Act

prevents items being

taken out of the collection

unless they're deteriorated beyond repair

or they're dangerous

or they're an exact replica,

an exact duplicate, in other words,

a coin from the same dye.

So even if the trustees wish to return them,

legally they're not allowed to at the moment.

So I think there's an impasse at the moment

which is difficult for

British Museum colleagues to deal with.

So it's essentially a political issue that

could only be resolved by a legal change.

As Merriman looks to the future,

he knows that the Horniman must continue

to challenge its colonial legacy

in order to maintain its appeal

amongst the local community.

His goal is that it should be

a museum for everyone.

I've written on the card

"Museums are for everyone"

because from my PhD, when I was a young man

looking at barriers to museum

visiting to all the jobs I've done,

including the Horniman,

my passion has been about

trying to understand

why some sections of the population

consistently feel that

museums are not for them.

I want to assert that

museums are for everyone.

What we're trying to do at the Horniman

is to realize that in practice.

Museums are for everyone.