Japanophiles: Francesco Panto

*First broadcast on August 3, 2023.

An Italian psychiatrist who uses an original "anime therapy" approach is the guest in this episode of Japanophiles, an occasional series in which we look at Japan through the eyes of residents who originally come from other parts of the world. Francesco Panto was bullied as a child but took comfort in anime. That led to his unusual approach to improving mental health. We hear Panto's story and learn how his work might help to address the widespread challenge of mental health issues among young Japanese.

Transcript

In 2020, Japan received

some shocking news.

In a UNICEF survey

on the mental well-being

of young people in 38 countries,

Japan ranked 37th.

Today we'll meet an Italian psychiatrist

who is tuning into Japan's troubled

young minds: Francesco Panto.

As a boy, Panto became a huge fan

of the anime Sailor Moon.

And he has since created a form of therapy

that actually makes use of anime.

It's a serious approach to psychotherapy

that harnesses his own interest

in animated films

for the benefit of young people in Japan.

Hello and welcome to Japanology Plus,

I'm Peter Barakan.

Today we present one

of our Japanophile profiles.

I'll be talking to Francesco Panto,

who when he was a

university student in Italy,

discovered the Japanese phenomenon

of “hikikomori,” or social recluse.

He came to Japan to learn more about it,

and at the age of 33,

he's now working

to help hikikomori patients

adjust to their surroundings.

And I'm off to have

a little chat with him.

Please.

Ah, hello.

- Hello, nice to meet you.

- Dr. Panto?

Yeah. It's my pleasure.

- Nice to meet you.

- Peter Barakan. Hi, nice to meet you.

Thank you for coming here.

Okay, so this is where you work?

Yeah, this is the laboratory.

When I'm working during the day in this,

yeah, exactly the same room.

Oh, really? This is actually your office?

Yeah.

This hospital is a little way out of town.

It's quite a quiet neighborhood.

Yeah, it's a little,

like, outside the Tokyo city,

because usually psychiatric hospitals

in Japan are very far away

from the center of the city.

Oh.

It is said that one in four

young Japanese adults

has seriously contemplated suicide,

and one in ten has attempted suicide.

A government report revealed that in 2022,

796 people under the age

of 20 committed suicide.

That was the highest annual figure

in decades.

Japan is the only G7 country

where suicide is the leading cause

of death for 15- to 39-year-olds.

Panto has been working

in Japan since 2018.

He sees patients six days a week

in four locations in and around Tokyo.

70 percent of those patients are Japanese,

and most have psychiatric disorders that

make everyday life difficult for them.

I made a big decision.

I took the plunge, and quit my job.

Panto has been seeing

this particular patient for a year.

He's in his 30s.

Previously the patient wasn't satisfied

with his treatment

and kept switching hospitals.

He's very receptive.

He goes beyond simply listening.

He engages very deeply.

I feel a strong sense of

being accepted as a person.

There's no sense of being judged.

I'm often told things that

I'm hearing for the first time.

Or things that I wasn't expecting.

With other doctors, I might not

be completely open to those ideas.

But with Dr. Panto,

I find them easy to accept.

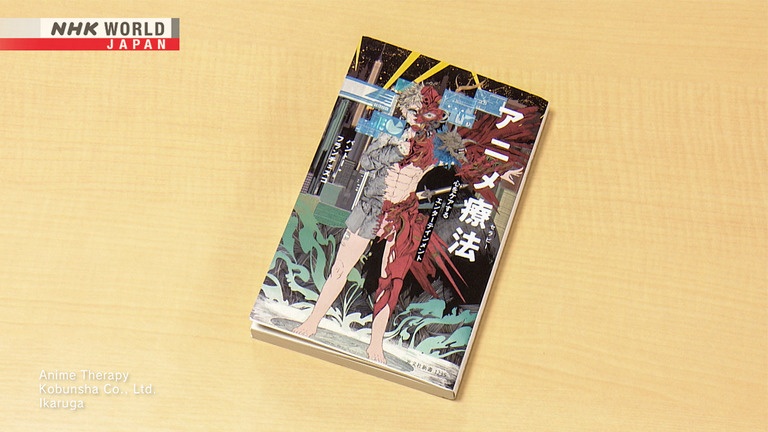

Panto first saw the potential of anime

when he was a graduate student.

His supervisor at that

time was Saito Tamaki.

What does he think about

Panto's novel approach to therapy?

We have therapy based on books,

movies, or other fictional material.

But a special focus

on anime is a new idea.

It's certainly a medium that easily

brings emotions to the surface.

And in my experience, after someone

becomes socially withdrawn...

anime is often the only thing

that they are able to watch.

So in that respect,

I do see a lot of potential.

Japan's many animations are highly

nuanced and emotionally engaging.

Panto regards these factors as crucial

in making progress with a patient

and enabling them

to see their condition more clearly.

It may be difficult to ask if you haven't

worked really in any other country,

but how is it working

as an Italian doctor working in Japan?

Yeah, I think it's very like fulfilling,

but it's very challenging for sure,

because if we think about,

like, psychiatry,

it is for sure a specialty medicine

that is most linked to words and culture.

So it's very challenging

from that point of view

because you have to not only

master the clinical aspect of medicine,

but you have also be able to engage with

the patient in a more like cultural way.

So it is a challenge for me every day,

but at the same time

I can learn a lot about

Japanese culture

in a way that is very unique,

and with a perspective that is very like,

privileged in a sort of way

because I can talk with Japanese people

about their suffering.

It's something that maybe usually you,

you can't hear about, you know?

Right.

So...so it's very difficult

from that point of view.

Also because patients are not

used to foreign doctors.

Like I think in America,

a patient is very used to...

to interact with all sorts of...

Sure. Sure.

doctors from all over the world,

and with all like, accent from...

different accents from the world.

But in Japan it's very

a uniform society as we know.

And so these kind of jobs,

like in medical field are very closeted.

So yeah for sure is...for them it's very

unusual to interact with a foreign...

Sure.

You studied medicine in Italy, right?

And I mean, being a medical student,

I'm sure is pretty

much a full-time occupation.

Yeah.

How on earth were you

studying Japanese at the same time?

Yeah, I was very determined to come

to Japan and to become a psychiatrist.

And when I start to study Japanese,

I think it was my third year

of medical school.

And I usually...

during the day I went to the lessons

and I try my best to take notes.

I will try to maximize my learning of the,

of the lessons. The medical lessons.

So in the evening hour,

I had more time to learn Japanese.

You taught yourself?

Yeah. I study for one year and three month

in order to take the N1

Japan language proficiency test.

Because at the time I was...

I was like trying my best to search

on the internet about,

oh, to become a medic...

a physician in Japan.

And actually,

there wasn't any information about that.

Maybe because it was all in Japanese,

and at the time

I didn't understand like enough.

Of course. Yeah. Yeah.

So I figure out like, in this situation,

I don't have any, any inclination about

what I'm supposed to do.

But if I learn like Japanese

at the best of my abilities,

for sure it will be a benefit.

So I start to study very hard

in order to take the N1.

And I actually was right,

because it actually was mandatory.

Now used internationally,

the term “hikikomori” was coined

in Japan in the 1990s.

It applies to someone

who doesn't go to school or work,

rarely speaks to non-family members,

and doesn't go out

for at least six months.

These days, it is said that Japan may

have 1.46 million hikikomori sufferers.

Since the pandemic, cases among

older people, too, have been on the rise.

The number of patients is swelling,

but it remains challenging to identify the

most appropriate treatment method,

or even facility.

In Japan, we're developing ways

to tackle the issue.

But I wouldn't say

that progress is always smooth.

Dr. Panto came to Japan

to research hikikomori.

And I want to help as many sufferers

in this local area as I can.

That's why I hired him.

His approach makes it easier for someone

to consider psychiatric care,

and that encourages more people to try it.

I hope he works here for a very long time.

This whole hikikomori thing, is, I guess,

one of the one of the things that

brought you to Japan in the first place,

and it seems to be perhaps

it's not uniquely Japanese,

but it's a particularly

Japanese phenomenon, isn't it?

Yeah, absolutely.

I think hikikomori is not

universally recognized as a

like cultural-bound syndrome.

I think from my perspective

we should consider hikikomori

like a cultural-bound syndrome.

Because in general

we can talk about social withdrawal,

and social withdrawal is obviously

the core symptom like for hikikomori,

because these...

there are people that don't go out.

Right.

But the difference is that

in Japan the reason for not going out

is different from the reason not for going

out in Italy or even in America.

Like for Japan usually,

the hikikomori start with futoko.

Futoko is a term that...

Not going to school.

Not going...yeah.

It's translated like school refusal.

And in Italy it's very rare,

this kind of presentation.

So in Japan, you have usually this kind

of very like talented young people

that because they feel

they are not like enough,

maybe they can't enter...

they couldn't enter the school

that their parents want them to enter.

They feel that they are not popular enough

and they start to

become very self-aware of that.

Japanese society is very strict

in that way.

They are some like goal you have

to master within certain like timing.

If you don't manage to do that,

you are considered like not manageable

from the mainstream society.

They think that they

don't have a second chance.

And I did, for example,

like in South Korea,

a lot of hikikomori people are actually

coming from Internet addiction.

Oh, okay.

So there are different reasons for these

similar phenomenon in different countries.

I see.

So if you analyze the reason and the

difference between the reason,

you can understand that there's actually

a social structure behind that.

So I think we have to differentiate

if you want... if you want to

find the best way to approach

this kind of phenomenon, yeah.

Right.

Francesco Panto was born in 1990,

in Sicily, Italy.

He has one sibling, a twin sister.

At the age of 11, he became a huge fan

of the Japanese anime Sailor Moon.

But his classmates didn't share

that interest.

I received a lot of bullying

from same age like boys,

because I...

my interests were a little different.

In Italy like we have

like a very strong soccer culture.

OK, it's like England.

And I was like more interested in like,

Sailor Moon,

or maybe we can say

like traditional feminine things.

OK.

So that was an issue from the kind of like

society that Italy was in those years.

So I was receiving a lot

of like bullying for that.

And that make me very isolated, you know.

Sure.

Yeah.

So after I grew up, I actually like gained

a lot of confidence

because my mother especially like

was always like saying to me that I,

I shouldn't like,

feel ashamed about what I was liking,

and it was perfectly normal.

And I think for especially for her advice,

I start to maybe regain

some self-confidence. Yeah.

But in those years I think

I was experience what

we can call futoko

in Japanese. School refusal.

OK, you didn't want to go to school

because you were going to get bullied.

Yeah. And even hikikomori.

Because my mother was very like frank,

and straightforward.

She was very proactive to make me

return to school

and to find...let me find my, my place.

So I even like, I think I changed school,

like three...two or three times.

OK.

Yeah, but eventually,

because my mother was so proactive,

I...after once I returned to school,

after that I didn't have any other problem

with that. Yeah.

Oh, interesting. OK.

He started to see himself

actually living in Japan,

and his academic interests

helped him move in that direction.

Wishing to study the human mind,

he set his sights on one of Italy's most

prestigious medical schools,

and he was accepted.

At my third year of medical school,

I already decided I want

to become a psychiatrist, but in Japan.

Oh, that sounds very strange to say.

But after, like I start

to learn like psychiatry,

I learned about the culture of psychiatry.

I became very fascinated with

the interaction between the culture

and mind... the human mind.

It could like lead to change

in the function of the mind, actually.

The cultural influence.

And also like I remember in my third year

when I was very young,

I started to watch anime

and manga and games,

and when I was a very like

a lonely type teenager.

And at that point,

like a lot of my mental health,

like supporting net was like...

was consisted about like anime and manga.

In a sense, like the anime

and manga characters were my friends.

Wow.

And when I grew up,

I start to wonder about my future.

And I understand

that I want to become a doctor.

At the same time when I was a child,

because my mother also is like a writer,

I also like always like being like

attracted by creative writing,

fictional writing.

After watching anime,

I would try to write my story.

So I was pretty fascinating about

that kind of fictional world.

Because from my perspective,

like the animation was a kind of drug;

a medicine for my mental health.

Hmm. Interesting

So I want to understand

if there was any medical rationale

around that kind of experience.

I figured out if I could

understand the reason

why I felt so relieved after like

watching an anime or playing a game,

maybe I could help some other people.

And Japan was the perfect place

to be from that perspective

because it is the most productive country

if we think about fictional production.

And yeah.

Hmm.

So was anime and manga the biggest factor

bringing you to Japan in the first place?

It was a very big part, but I think

it was a combination of factor,

because psychiatry

was also another big pillar.

Of course. Of course.

After start to study psychiatry,

in my third year of medicine,

in my, my medicine book,

I read about hikikomori and there was

a mention about Saito Tamaki professor.

And when I first read about him,

I thought that he was already passed away

because he was a very described

as a legend in that work.

Oh, I see.

But after like doing my research,

I actually, like, discovered

that he was safe and sound.

He was still working.

At Tsukuba University.

So I figured out maybe I can

study hikikomori phenomenon

and understand better

about culture behind.

He came top of his graduating class,

received his medical license—

but chose not

to practice medicine in Italy.

You wanted to come to Japan partly

because there's this Professor Saito,

who was the big expert in hikikomori.

And you actually studied with him,

- didn't you?

- Yeah.

What sort of things did you learn

from him specifically?

He was like prompting me

to research what I like most.

At the time I understand maybe the thing

I wanted to research most was

the relation between yes, hikikomori,

futoko, and the like fictional narratives.

So anime and games.

And to understand if

there is any kind of

positive emotional like benefit

from this kind of activity.

From this kind of fictional narrative

conception behavior.

So actually he encouraged me

to research what I like the most.

The research lab of Professor Saito

is a very unique one.

It's in social psychiatry

and social welfare.

So I learned a lot

about like social stigma,

about the mental health issue in Japan.

And his team is very proactive

to deconstruct the stigma,

and to let like Japanese people,

the patient,

like receive the actual help they need.

A world authority on hikikomori,

Saito helped to spread awareness

of the phenomenon.

Panto left Rome and came to Japan

specifically to seek

this respected doctor's guidance.

Saito says Panto stood out from the start.

He was talented, dedicated,

and eager to learn.

And as you will have realized,

he is also an otaku.

In many ways, he seemed very Japanese.

Under Saito's supervision,

Panto began to develop anime therapy.

Anime characters convey a wide range

of emotional states.

Anime therapy uses this as a key

to unlocking a patient's condition.

Peter is going

to experience “anime therapy.”

First of all, he watches a scene

in a drama called “Blue Orchestra.”

The main character

is an accomplished teenage violinist.

While his father, too, is a violinist,

the two do not get along.

But being a member of the school orchestra

enables the young man to grow as a person.

In the scene we're using in this session,

the main character recalls violin practice

with his father in the past,

and then can't get to sleep.

So we watched a scene

from the anime Blue Orchestra.

From your personal experience

there is something like in your life

maybe that you can

like relate this scene to.

Personal, or like space that

remember you... something very unpleasant

that you want to... not to stay

in touch with that place or person.

Well my parents were divorced.

It wasn't traumatic in that way,

although I don't know.

When I was in my primary school years

I can remember my parents used

to fight a lot.

I remember that my brother,

when I spoke to him about it much,

much later on, he'd forgotten about it,

so I presume he has suppressed

the memory of that.

Is it effective with the patients

that you're dealing with?

If a person have a very strong connection

with the production we are talking about,

and there is very clear behavioral

or emotional problem you are dealing with,

and could be very simple tool to make

a patient open up about themselves.

So at least like I can, I can see that

the relationship with my patient toward

this kind of therapy improved,

in the sense that they are able

to express their feeling,

in a more like effective way.

So yeah, also, no,

this is that kind of effect as well, yeah.

Yeah, I guess because I'm not a patient,

this doesn't necessarily apply to me,

but I can understand

how it would work with a patient.

It does seem that it would probably

be quite effective. Is it?

That's interesting.

Thank you.

Panto is developing a new way to apply

anime therapy and help his patients.

It's a computer game.

He has devised original characters

for the game, and a storyline.

If we think about the more...

most effective anime therapy,

I think the most effective will be a game.

Because a game is not only

a story you enjoy watching.

You can interact the characters

in the story.

I want to develop a game that firstly,

is very fun to play.

In order to do that,

I have to convince the people that work

in the entertainment industry

that is a good idea.

And in order to be sponsored by them,

I want to prove the effectiveness

of my theory.

So in...for that reason,

I am developing a very simple game

for such purpose.

But the final aim is to create a new,

a new category of game.

Like we use the camera,

the sensor in maybe a smartphone,

to make a profile of the player.

So we know

that the player in that situation

is like more prone

to anxiety or depression

and the facial expression

of the player shows like sadness.

And we know the personality of the player

and basing on that profiling,

we provide an experience

that is tailored to the player.

So can...the character of the game

could interact in a very

personal way with the player.

Understanding the emotional status

of the player.

So this would presumably

be using AI as well.

Exactly. Yeah.

But it's not only based on database...

a general database.

But the database is, like, constructed,

builded on the player profile.

I think it could be very different

from the experience we have today.

Okay.

I mean, you're working in the daytime,

you're working in the evenings.

You're creating game software, or...

Do you actually have any time to sleep?

Very little, actually. But I do my best.

Okay.

The last question in these Japanophile

programs is always the same one.

What is Japan to you?

Yeah, Japan for me, is very...

it's a lot of different things.

But the common denominator is like,

I will say, the Japanese word ibasho.

When I was a child,

I felt that I wasn't fitting anywhere.

So Japan and Japanese culture

provide me ibasho.

When maybe I'm sad,

maybe I'm not motivated,

I'm surrounded by the culture I love.

So maybe I go to anime cafe.

Or I go shopping for some goods I like.

Or I'll talk with my friends about the...

the anime we are watching.

So I found comfort and I found,

like, meaning.

It's very fascinating,

and very stimulating for me to be here

in this point of time

because I could be part of that machine

that produce culture,

that I think in the future

will be appreciated.

Hmm. Interesting. Thank you very much.