Japanophiles: Gregory Khezrnejat

*First broadcast on August 11, 2022.

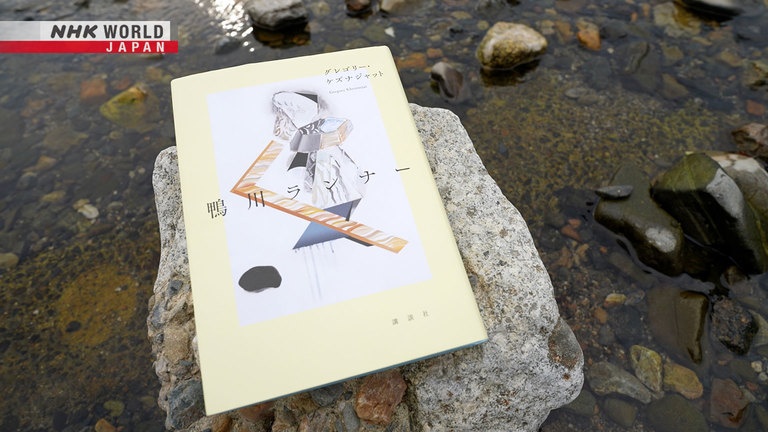

Gregory Khezrnejat is an author and university associate professor from the United States. In 2021, his Japanese-language novel Kamogawa Runner won the second annual Kyoto Literature Award. The novel is inspired by Khezrnejat's early experiences in Japan. In a Japanophiles interview, he talks to Peter Barakan about the challenges involved in expressing yourself in a second language. He reads excerpts from the book, and talks about his work as an associate professor of literature at a Japanese university.

Transcript

Hello, and welcome to

Japanology Plus. I'm Peter Barakan.

Today we present one

of our Japanophile profiles.

The book I'm holding here

is called “Kamogawa Runner,”

Kamogawa being the name of a river

that runs through the heart of Kyoto.

The book is the debut novel

of Gregory Khezrnejat,

an American from South Carolina.

He wrote the book in Japanese,

and in 2021, it was awarded

the Kyoto Literature Award.

Gregory is an associate professor of

literature at Hosei University in Tokyo,

which is where I'm standing now.

I've come to talk to him about

how he came to write his book,

and also about language

and culture in general.

This is the one.

Gregory.

Ah, good morning.

Nice to meet you.

Hi, nice to meet you. Come in.

Thanks a lot.

This is your office, huh?

Yes, this is where I work.

Okay.

Well, I see you've got

well-stocked bookshelves,

which, of course, is only to be expected,

given the nature of your work.

So most of these books are

related to Japanese literature.

Have you read all of these?

No, I've read parts of all of them,

but I haven't read

all of these books in full.

Okay.

I hope to one day,

but never quite get there.

Okay.

I can imagine it'd be quite a task.

Khezrnejat's debut novel

is titled Kamogawa Runner.

It tells the story of a young American man

who regularly runs by the Kamogawa river.

When he first visits Kyoto

as a high school student,

everyday scenes look like

something from a fairytale.

But later, when living in Kyoto

as an English teacher,

his perspective changes.

Being an outsider makes him stand out,

and it proves difficult

to blend into society.

The protagonist moves

to a place near Kamogawa.

He keeps struggling to fit in.

But after encountering the work of

Tanizaki Junichiro, a 20th-century author,

a new world begins to open up.

First of all, congratulations

on winning your award.

Thank you very much.

The book reads like an autobiography.

How much fiction is there in it, in fact?

I think there's probably more fiction

in the book than most readers realize.

Oh, really?

When I started writing it,

I did draw on my personal experience...

the broad strokes of the story.

An American learns Japanese,

comes to Japan, lives in Kyoto,

eventually studies Tanizaki Junichiro,

moves to Tokyo.

Those are the same as my own life.

Right.

And I also used my journal

when I was writing the story.

I went back to the journal that

I was keeping when I lived in Kyoto,

and I used parts of it within the text.

So did you keep a fairly detailed journal

when you were living in Kyoto?

I kept the journal initially as a way

to start...practice writing Japanese.

Oh, you wrote it all in Japanese?

It was written in Japanese, right.

Oh right.

So was there something

in the back of your mind

about writing a novel at that point?

At that point, no.

At that point, it was really just

wanting to try to

practice and learn to write better.

And at that time,

I was already preparing to

hopefully go to graduate school

and study Japanese literature.

So just as a way to get a handle

on the language for myself,

I was writing to that end.

The Kyoto Literature Award was established

with the aim of showcasing Kyoto

as a wellspring of new culture.

There is a “General” category, and—

for foreign writers—

an “Overseas” category,

to which Khezrnejat

submitted his manuscript.

The story makes striking

use of the second person.

It begins, “When you first visited Kyoto,

you were sixteen.”

This unusual approach

contributed to Khezrnejat's success.

His work won both the “Overseas” award

and the “General” award.

In the book...I'm sure this is something

that everybody is going to remark on...

you don't use “I” and

you don't use “he,” you use “you.”

It's almost like there's another you

looking almost like down on you,

taking it all in from almost a different

dimension or something.

How did you come up with that?

I don't think I've ever seen that before.

It's one of those things

that people try to avoid because

it very easily sort of devolves

into being sort of

a self-absorbed narrative.

I think if you write...

A lot of creative writing instructors,

I think in the first class, they say,

“Don't use the second person.”

Oh, really?

“It's too self-indulgent. Don't use it.”

And there's truth to that, I think,

but it's less common in Japanese.

You don't see it so much in Japanese.

I think that has to do

with maybe the difference

in the way we use the second person

in English versus Japanese.

And that is to say, in English,

we use the second person a lot of times

to universalize experience.

“You know how when

you go to the train station...”

Oh in that sense, yes, yes.

Exactly, right.

And you don't do that in Japanese.

Right.

But in any case, I thought it was sort of

interesting in this story to use it,

because when I started writing the story,

I started with the third person,

and writing in the third person I felt

there was too much distance from

the narrator to the protagonist.

And then I tried

writing in the first person,

and I felt like there

wasn't enough distance

between the narrator and the protagonist.

So just as I was experimenting with

different ways to write the story,

the second person started to

seem like the most natural choice.

What was the message that

you really wanted to get across to people?

The main message in this book?

I don't think there was so much a message

that I was hoping to get across.

There wasn't...there's not

something that I'm hoping...

a single idea that I'm hoping the reader

will take away from it.

But I think it was more for myself.

Through the writing process,

I wanted to explore,

“What does it mean to

speak a second language?”

Or,

“What does it mean to come into contact

with a culture that's not your own?”

So, for example,

there's a scene in the book

where the main character goes to a temple,

and his teacher is

talking about the omamori...

so, you know, omamori...

like this traditional Japanese luck charm.

You can call it an amulet or a charm,

and you get across the main meaning.

Right.

But at the same time, I think,

for example, if you live in Japan

and you speak Japanese,

when you hear the word “omamori,”

there are a lot of images

that go along with that.

So you think of people going to a shrine

and buying that at the stalls.

You think of maybe high school students

when they're going to

take their entrance exams,

and you see at the station they've all got

omamori hanging from their backpacks.

You think of all those images,

that go along with that word,

and all of that necessarily gets cut off

when you translate the word.

Right.

Sometimes I think those are

maybe the more important part of

the word rather than just the meaning.

Gregory Khezrnejat was born in 1984,

in South Carolina in the United States.

Having an Iranian father offered a window

on a different world of experience.

His hometown had lots

of Japanese businesses,

and Japanese was one of the languages

available at his high school.

This was Khezrnejat's first

encounter with the language.

At the age of 14, was there something

that hooked you specifically,

or was it just, “This might be fun”?

It was partially just a sense that

it was different from English.

My father is from Iran,

and he would have in

the house books written in Persian,

and he would get letters from family.

And I remember looking at him

reading and looking at him writing

and thinking it was

just sort of amazing that

these symbols that didn't even look like

letters to me as a child...

When you only know the alphabet,

the idea that they could signify something

and communicate meaning

was sort of hard to understand.

And so I always wanted to try learning

a language that didn't use the alphabet.

That was a different character set.

Huh.

And I think when I saw Japanese,

among those options,

it seemed like a good chance to try that.

In the year 2000, at the age of 16,

Khezrnejat visited Japan

on a school study trip.

The protagonist in Kamogawa Runner

has a similar experience.

You say, I don't know

if it's true or not, but...

it was the first train trip

that you'd ever taken.

That's actually true.

It was one of my first trips

out of my hometown, really.

And my hometown is a very small place,

so I think many young people,

when they're in high school,

they might go to

New York for the first time,

and then that becomes sort of the place

that they want to go again.

Sort of a symbol of

their young dreams, right?

And I think that for me,

that's what Japan ended up being,

because it was that first

experience of leaving home.

It was that first experience of

seeing a different world,

a different way of living.

Wow, I mean,

to have come directly from

a small town in South Carolina

to Kyoto and then,

well, and Tokyo as well.

That must have been really...

it turns your head around.

It was a shock to the system.

I think the biggest...the thing that

left the biggest impression, though,

was not just the country itself,

but seeing a world

that functioned for 24 hours a day

in a language that was not English.

So up until that point, I had seen

my father speaking Persian.

I had seen people speaking other languages

in my high school classrooms.

But that was the first time that

I realized that other languages...

that the world...

basically it relativized

English in an interesting way,

and it made me realize

that the world I knew

and the way it was described in English,

that was only one way of seeing the world.

Khezrnejat went on to receive degrees in

English Literature and Computer Science

from a university in his home state.

In 2007,

he came back to Japan again

to take part in an official

cultural and educational program.

He was an ALT,

or assistant language teacher,

at schools in Kyoto Prefecture.

I think in the book...

the book deals a lot with the idea of

being out of place

and what that feels like.

So you see the protagonist of the book

in different situations

where he doesn't fit in naturally.

So, for example, the main character,

when he goes to teach as an ALT,

he feels that he's maybe treated

not so much as a person,

but he's more like a tool, right?

He's the native teacher, right?

Right.

In fact, the Japanese teacher he works

with never bothers to learn his name.

He's always referred to

as “the native teacher.”

Exactly.

In my early years in Japan,

when I was here,

I certainly felt that sometimes.

Those sorts of situations and

encountering that sort of treatment,

it does give you a sense

of feeling out of place.

But also, I don't think

it's necessarily a bad thing.

I think that there's a productivity that

comes out of feeling out of place.

By feeling out of place,

it gives you a chance to look at things

maybe with a more objective eye

and maybe I think a lot of

literature comes from that.

A lot of literature comes from someone

trying to deal with the feeling

of being out of place.

After two years as an ALT,

Khezrnejat began studying

Japanese Literature as a graduate student

at Doshisha University in Kyoto.

His studies there continued for

seven years and culminated in a PhD.

So after you quit and went to graduate

school, what was the biggest difference?

I think one of the biggest

differences between

being an ALT and being a graduate

student was the community around me.

So in the school, I was...

I was an English teacher.

I was only there for

a short-term contract,

and that affected my

relationships with people around me.

But when I was in graduate school,

I think all of my classmates

and professors, for the most part,

treated me as just another student.

So in a good way,

they treated me like everyone else.

But at the same time,

there was never a sense that, “We're

going to put on the kid gloves for you.”

We're kind of there

in the ring with everyone else.

Right.

And so sometimes that could be sort of

a painful experience.

Because, of course,

if it's a discussion of

Japanese language...

Japanese literature in Japanese language,

me, at that time, having only

lived in Japan for a few years,

I didn't have the words to

say everything I wanted to say.

So it was frustrating in that way.

Studying literature is not

easy in any language, I think,

even in your own language, probably.

Doing it in Japanese has to

be that much more difficult.

How much of a struggle was it for you?

It was a struggle.

I remember going into my first class

and looking at the reading,

and it was so different from the texts

that I had been reading before,

up to that point.

I had only been reading

sort of postwar texts

that had been written in

just the past few decades.

And then to go to something that

had been written in the late 19th century

or something that had been written

even in the 1930s and 1940s,

the text was radically

different sometimes.

So there were days where I felt like,

“Oh, I might have made a big mistake.

Maybe it's time to go home.”

But it's interesting you said that

it's difficult to study

literature in any language,

and even more so in a second language.

I think that's true, but at the same time,

there are some benefits

to studying in a second language.

Every single word I was looking at it.

What does this mean?

Am I sure that I know the meaning?

I think I know the meaning,

but maybe 100 years ago,

it meant something different.

And so in that way,

it trains you to look at the text

carefully and analyze every bit of it.

Would you discuss these things amongst

yourselves with the other students?

We did.

That was one of the best parts

of being in the program.

Japanese universities, they're very much

based around a seminar - a zemi.

And so you have a close community of

students, and you'll spend years together.

And in Japan, you have these sort of

senpai-kohai relationships.

You have these sort of

senior and junior students,

and the senior students

take care of the junior students.

And so I had some really

great senior students,

some great senpai students

there who were really helpful.

Fukuoka Hiroaki was one

of Khezrnejat's senior students.

He is now an associate professor

of Japanese Literature

at Kwansei Gakuin University.

He looks back at the time

he spent with Khezrnejat

when they were studying together.

When I remember that

time in graduate school,

I was still quite young.

I think Fukuoka-san and

the rest of our zemi, we all were.

And so there was maybe

some bouncing off of each other at times.

There's a very particular environment

around graduate studies,

and particularly Japanese literature

graduate studies here in Japan,

there's a certain atmosphere there...

that sense that all of us,

we kind of want to show what we know,

and that sort of competitiveness

that drives us.

And of course, looking back,

it can seem a little bit immature,

maybe, for all of us,

but at the same time,

it's also probably a necessary step in

becoming a researcher to have that period

where you do sort of compete

with each other in that sort of way.

It was very nostalgic to see that video.

Good afternoon.

Khezrnejat teaches three classes

a week at his university.

The thing you've got to be

careful about with plagiarism...

there are two forms, right?

These courses are in the Faculty

of Global and Interdisciplinary Studies,

which offers a four-year undergraduate

program taught entirely in English.

Do you think that's

meant to be taken literally?

So do you think he's seeing real ghosts,

or is it more of a metaphor?

Like he's seeing a memory, maybe.

What do you think?

The ghost is like...himself.

In this class,

first- and second-year students discuss

the appeal of literary works.

Then they learn how to distill

those points into a written report.

What would you think...

this story is translated, right?

It was originally written in Japanese,

and it's been translated into English.

Do you those were

the same in the original text,

or do you think there might be some

difference there in the pronoun usage?

Yeah, I feel like it's

not specifically said in the sentence.

In a roundabout way,

it feels like it's said.

I don't know.

Interesting, interesting.

OK, let's hold onto that, OK?

This class is for fourth-year students.

They're discussing a Japanese short story

that has been translated into English.

Peter is also taking part.

“I can't do this job,

because what if I made a mistake?

Instead I'm just going to have to stay

at home, and let Dad pay for everything.”

Right?

What about you guys?

Did you feel sympathy for

the character as you were reading?

Or...how did you feel

towards this character?

Yeah, I don't think

I felt any sympathy, actually.

No sympathy with this character?

In Khezrnejat's classes, the students

are free to express their views.

For him, discussion is essential.

Does your work here teaching

literature to the students here

connect at all to your work as a writer?

I think they're separate,

but they are connected.

I think if you spend a lot of time

reading and writing on your own,

your world can become very small.

And that's not always a bad thing;

there are creative things

that can happen there.

But it's a good idea to, you know,

have a chance to speak with others.

To discuss these ideas with others.

So being able to sit here for three hours

a week with my seminar students

and talk about literature with them...

I hope it's good for them,

but it's also very useful for me.

It's very stimulating.

Khezrnejat is currently

working on two new stories:

one set in his home state

of South Carolina,

and the other in Tokyo.

Both stories examine language,

culture and identity.

And he hopes to explore various

complexities related to these themes.

For me right now, living here in Japan...

right now we're speaking in English,

but every day in my daily life,

I mix both languages.

So I'm using Japanese some of the time,

English some of the time.

So in a way, it feels to me natural

to use Japanese for my writing right now.

And at the same time,

I think there's a value in writing in a

language that sort of resists you.

So what I mean is...

When I write in Japanese,

the language never lets me forget

that I'm not a native speaker,

and I'm always second guessing my choices

and wondering if

I'm using the right phrase or

am I saying really what I want to say?

Or...I'm always thinking

about it in that way,

and I actually think that's

probably healthy for someone to feel

when they're trying to

write something creative.

So, in a way,

I think people tend to think that

writing in your first language is easier.

And of course, in some ways it is.

But at the same time,

I think there are a lot of benefits that

come along with

writing in a second language.

The last question on these Japanophile

programs is always the same one.

What is Japan to you?

I'm not sure.

I don't really spend too much

time thinking about Japan.

I used to live in Kyoto,

and when you say the word “Kyoto,”

I think people have many specific images

they associate with that.

But when you actually live there,

you see that the city is much more

complicated and much more interesting

than just the simple images of Gion

and festivals and things like that

that people have, right?

I think the same thing is

true of Japan as a whole.

When we start talking

about the word “Japan,”

suddenly the conversation becomes

very narrow and sort of very flat.

I think it's more interesting

to try to look at some of

the complexity that gets lost

by putting that word aside and trying to

look at what's right in front of us.

Okay, thank you very much.

Thank you for having me.