Cooking Utensils: Craftwork Ensures the Future of Traditional Cuisine

Cooking utensils influence Kyoto cuisine, helping to bring out the inherent flavor of local ingredients. Artisans and chefs believe that upholding the handicrafts sustains the taste of Kyoto.

Transcript

Japanese cuisine, such as elegant kaiseki or Buddhist vegetarian cooking,

focuses on presentation and the inherent flavors of the ingredients.

A chef's skill and the finest utensils are required to entertain guests with the best cuisine.

Specialists hone knives to their sharpest based on their owners' style and how the knives are used.

The delightful thing about cooking knives is they

bring ingredients to life and enrich our diets.

Hammering metal produces pots of all shapes and sizes.

I take pride in producing items

to customers' specifications.

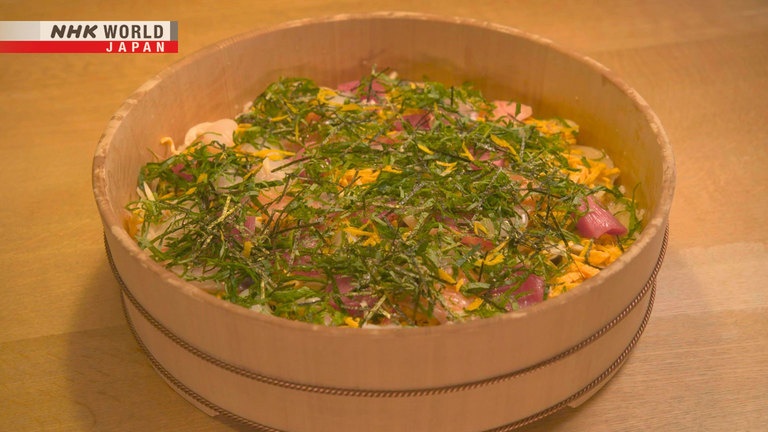

Wooden tubs and containers have been preferred for making sushi and storing rice since ancient times.

It is the focal point in gatherings, like

when people want to make "chirashizushi."

When used over years, it becomes

part of your home cooking.

Certain dishes never

taste the same without it.

Core Kyoto brings into focus the artisans and chefs

who believe that upholding the tradition of handcrafted utensils sustains Kyoto cuisine.

A keen kitchen knife is indispensable to Japanese cuisine.

It will slice fish without hacking at the flesh.

A superior knife is thought to improve the appearance and change the texture of food.

Sashimi is a good indicator of how good a knife is.

The knife is as important as your fingertips.

You honestly can't get by without one.

Sashimi is prepared by just slicing, so

the flavor changes depending on the cut.

That's also true of the texture

and appearance.

Learning to cook, I believe,

starts with how to handle a knife.

One man specializes in "hocho," or kitchen knives, and promotes their virtues.

Hirose Kouji is a self-styled "hocho coordinator" whose work goes beyond sales.

A "hocho" is an edged tool.

This extraordinary tool is

essential to food preparation.

Edged tools include scissors,

chisels, planes and ordinary knives.

But as a culinary tool, the "hocho"

supports human eating habits.

It's a fascinating tool. The biggest part of

my job is conveying a "hocho"'s superb potential.

Japanese cooking knives come in a variety of shapes for different uses.

These are the three basic types of "hocho."

The "usuba-bocho" to chop vegetables,

the "deba-bocho" to clean fish,

and the "sashimi-bocho" to slice fish.

The "deba-boucho" has a thick blade to chop through the bones and other hard parts of fish.

The "sashimi-boucho" has a long, thin blade to neatly slice through fish flesh for sashimi with a clean cross section.

The "usuba-boucho" has a thin blade to peel, cut, and chop vegetables without damaging the fibers.

Clean-cut corners stand straight and

stimulate the tongue when put in the mouth.

The brain registers the morsel

as delicious.

Even in grilled, simmered, and other

cooked foods, if the cuts are clean,

the food is cooked evenly,

and the flavor is consistent.

Along with the five flavors of sweet,

salty, bitter, sour and umami,

you have another - "edge."

And you can't get that

without these cooking knives.

From this belief that a hocho's cutting ability influences flavor,

one of Hirose's jobs is adjusting knives to ensure they are at their sharpest.

I hold it up to this light to check

that the blade's line is straight.

First, he must adjust the distortion and warp of the blade before he can properly sharpen the cutting edge.

Next, he makes the edge thinner and angled to suit the owner's predilection and the knife's use.

The edge was rounded like this,

but I'm making it thinner.

The edge is pointed, so it will cut,

but I'm making the angle more acute.

Doing so enables a gentler cut,

preserving the goodness of the ingredients.

Hirose performs a process that brings a hocho to its peak condition so it will give a sharp, delicate cut.

He starts with a rough-grain whetstone then progresses to a finer grain to slowly make the edge thinner and angled.

And he uses this whetstone to finish the blade.

The whetstones I've used to

this point are synthetic.

The one I'm using here is

a natural whetstone from Kyoto.

Since this is natural, it has both

coarse and extra fine grains,

so it can't be classified

by grain size.

If you did grade it, this synthetic one

is 1200 grits,

and this natural one is finer at

between 10 and 12 thousand grits.

Hirose believes that this natural whetstone gives each "hocho" he sharpens a special edge.

The cutting edge of a steel "hocho"

is serrated, like this.

Honing the serrated edge on a fine

whetstone makes the serrations finer.

When honed with the finest, natural, Kyoto

whetstone, the edge becomes almost straight.

There is little resistance when the blade

slices, and it stays sharper longer.

Many professional chefs rely on Hirose's knowledge and skill.

When we don't know if we're doing it right,

we turn to Hirose, like we would a textbook.

We even ask him

about the little things.

Hirose can tell a chef's style

by just looking at their "hocho."

So he's someone reliable who can correct

knives and teach you how to hone them.

Kyoto has an 800-year history in the production of natural whetstones,

which are vital for maintaining the knives and bladed tools used in various fields.

The area from Saga-Arashiyama to Kameoka has long provided the best stones for finishing blades.

Tanaka Nobuaki, who sells whetstones, hunts in the mountains for suitable stones.

Relatively speaking, Kyoto has

some of the finest grade whetstones.

These stones are quarried from a geological strata which was deposited 200 million years ago.

I quarried these stones

three days ago.

You tap them with a hammer

and listen to the tone.

Unsuitable stones have a low tone,

and good ones have a high tone.

I bring back this much, but only 10%

of them will become sellable whetstones.

Tanaka essentially works by hand to extract the valuable stones so as not to damage them in any way.

I look for good layers. It seems like

there's a lot, but only some are useful.

This is what I take.

Tanaka takes the stones back to his workshop to sort the best ones to transform them into whetstones.

I take great joy from the fact that people

find my products useful.

It makes me feel good.

Customers give me feedback which I use

to provide them with better stones.

Whetstones refine the cooking knives which in turn sustain Kyoto cuisine.

Cooking pots made of copper are preferred by many chefs.

When Aoki Taiki opened his restaurant in 2013, he decided on this style of pot for his signature dish, duck hotpot.

I've been using these

for 10 years.

They haven't broken or deteriorated.

They're strong and delicate.

As far as I'm concerned,

no better pots exist.

Aoki's pots were made by a workshop that has specialized in cooking pots for over 70 years.

Their products are favored by amateur and professional cooks alike.

Terachi Nobuyuki continues to employ a traditional method of hammering metal sheets into various forms.

You don't have to hammer the pots,

but they tend to warp and dent with use.

Hammering hardens them, and they don't

dent or deform when slightly bumped.

Terachi uses aluminum, brass, and copper.

Molding the pots is done by hand at this workshop.

Hammering the pots embellishes them with a distinctive pattern.

It's not a design. Hammering

toughens the pot and gives it a long life.

It becomes denser,

more compact, and harder.

Two types of tools are used to mold the metal - hammers...

...and steel stands that hold the metal in place while it is worked.

Terachi discerns the thickness of the metal from the tone of each strike and the vibration felt through the handle.

To ensure a consistent thickness, he uses his left thumb to rotate the pot at a steady speed,

while his right hand hammers with consistent strength and rhythm.

You strike flat on this surface.

Not at angles like this.

The hammer must hit the same spot.

Both legs are required to fix the pot in place, and the position of the left hand is important.

You turn it a bit at a time.

You set the interval like this

and rotate it for a perfect circle.

For the vertical curve, you hold it with

the arch of your feet, then push and pull.

Coordinating the hands and feet to create a perfect shape is testament to the craftsman's skill and experience.

Chef Aoki admired Terachi's expertise so he chose to use the pots for his signature duck dish.

If the pan is roughly hammered,

or the thickness and width are uneven,

heat is not distributed accordingly.

The thicker parts are harder to heat,

and the thinner parts overheat.

Consequently, some ingredients are cooked,

others undercooked, and this affects the flavor.

Utensils are essential, and the value of the dish

of course alters depending on utensil quality.

Terachi's workshop also retails its products to the average consumer.

They stock over 300 varieties of Western and Japanese-style pots to suit any cook's strength and the size of their hands.

They also manufacture and sell everyday items, such as wine coolers and cutlery, to suit modern needs.

Terachi's father, Shigeru, opened the retail store in 1994.

He felt there was no future as an artisan just selling his pots to wholesalers.

He wanted to directly hear customers' impressions.

Each era has its cooking trends,

so you have to learn to ride them.

And that's not easy to do.

Over the years, the Terachis have adapted their handmade utensils according to culinary fads.

Their products also attract young consumers.

This cafe boasts latte art created with pitchers made by the Terachis.

Barista Nonomura Tomotaka came second in a 2022 latte art competition held in Japan.

I chose this because I want to use

well made, quality equipment.

The copper pitcher conducts heat well, and Nonomura can tell if the milk is the right temperature just by holding it.

With the aim of improving his art, he placed a custom order for a pitcher, with minor changes for easier use.

He had the handle slightly lowered so he could more easily adjust the angle when pouring.

He also had the spout adjusted so he could precisely control the flow of milk.

Unlike other pitchers, this one

produces a sharper image,

and makes a clear difference

when used with other pitchers.

I enjoy making products that are used

by people who appreciate them.

We do what we can when people come in

with requests to make items easier to use.

I take pride in producing items

to customers' specifications.

"Chirashizushi," or scattered sushi, is served at special occasions.

A wooden tub is essential when mixing the vinegared rice.

The wood absorbs and then slowly releases moisture to produce soft, delicious sushi rice.

The rice doesn't stick.

This is made from "sawara" cypress,

so it smells good.

If you mix it in any other bowl,

the rice becomes too sticky.

Wooden tubs are full of the wisdom and

aesthetics of old, so they can't be easily imitated.

Kondo Taichi specializes in making sushi tubs and other wooden containers.

He uses cypress and sawara cypress to fashion tubs and buckets, like these, which are used for water and liquids.

We make barrels and buckets by

assembling hoops and wooden slats.

Tubs are assembled so tight that not even one drop of water will leak.

It requires elaborate techniques to perfectly align the adjoining wooden slats.

I create templates like this to suit

the type of tub I'm making.

I take it -

and fit the slat into the corner.

This is still not perfect. Can you

see the light peeking through?

Even a paper-thin gap when making a tub

with 15 or 20 slats is a large margin of error.

Kondo uses a special plane to adjust the slats.

The blade is sharpened a special way, raised

in the middle and sloping on the sides.

I make fine adjustments

using different places.

If I use the middle,

the angle's the same.

The outside is shaved on the right.

The inside, on the left.

Light is still peeking through on the inside,

so I'll shave a little off the outside.

Now it's a perfect fit.

Uncompromising craftsmanship is the essence of Kyoto aestheticism.

Utensils, which combine beauty and function, play a role in how much a meal is enjoyed.

A properly made tub can make

any cooking look special.

I sometimes use one for "onigiri,"

and I use it as a serving platter

on special occasions, such as New Year.

In a wooden tub, the cooking

looks sumptuous. It's like magic.

Despite having a long history in Kyoto, demand for wooden tubs is decreasing in favor of plastic products.

To boost awareness, sake cups using the same techniques have made an appearance on the market.

It's hard to suddenly get young people

to buy and use sushi tubs or rice containers.

But if there was one item on the table

made from specially selected, real wood,

I think word will spread.

The sake cups are basically made in the same way as other tubs.

Since they are smaller than average tubs, they require more intricate workmanship.

You can showcase your expertise.

They're small, but the work is detailed.

I wanted to give them a graceful finish,

so I could show that side of the craft.

No matter what item he is working on, Kondo takes pride in his work, never cutting corners.

We also repair tubs.

By doing so, we can learn about

the techniques coopers of old used.

That's to say that the items I make now will

outlive me, and someone will see them later.

I don't want them thinking

I did a slapdash job.

On this day, "hocho" coordinator Hirose Kouji is holding a kitchen knife honing workshop.

The participants, most of whom are amateur cooks, bring along their own knives to learn the correct way to sharpen them.

No effort, right?

When you slice with this, the cut is clean,

and the corner is sharper.

This is the "hocho"'s edge.

This brings out the best of the ingredients.

Grasping this will enhance

your daily eating habits.

Hirose also holds workshops at Kyoto schools in the hope that the students will become interested in cooking

and realize the importance of quality utensils and their upkeep.

Handmade utensils support Kyoto cuisine.

These tools produced with expert skill influence the taste and texture of the food.

Protecting and passing them on is essential to the future of Kyoto's culinary culture.