*Click here to read the first installment: Outline of disaster

Three of six reactors were in operation on March 11, 2011. A magnitude-9 earthquake triggered a massive tsunami, and the waves flooded almost all of the buildings that house reactors. The cooling systems in the operational No.1, 2 and 3 reactors were disrupted, causing meltdowns.

Hydrogen built up in the No.1 and 3 reactor buildings and led them to explode. Hydrogen from the No.3 reactor then flowed into the No. 4 reactor building, which suffered the same fate. The chain of accidents released a massive amount of radiation.

What the process entails

The decommissioning work is expected to take up to 40 years. The process involves dismantling the plant while mitigating the risk posed by radiation. The Japanese government and TEPCO have devised a roadmap broadly divided into three stages. The effort is now moving into the second phase, and officials are considering the timing for the removal of fuel debris from the reactors. The reactors were put on a stable footing in the first stage, with decommissioning now entering a full-scale phase. Despite this progress, some of the technological underpinnings for work planned for the third stage have yet to be worked out.

The biggest challenge

The biggest hurdle is removing the molten nuclear fuel and structural elements that constitute the debris inside the reactors. Robots have been tested inside each nuclear reactor's containment vessel, with some success in the No.2 reactor, where sediment resembling radioactive debris was discovered in 2019.

TEPCO plans to carry out a small-scale test to assess the feasibility of removing debris from reactor No.2 in the latter half of the 2023 fiscal year. The work was initially scheduled to begin in 2021 but has been postponed twice. It is not clear when the shift will be made from preparation and assessment to actual removal efforts, nor is there a detailed plan for removing all the debris as yet.

The plan for treated water

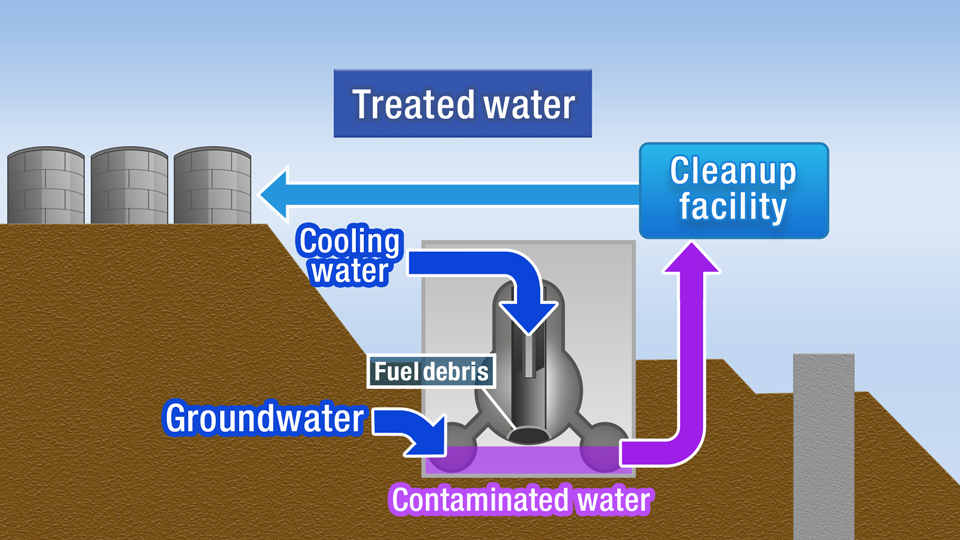

The decommissioning work is often described as a battle against water. Water used to cool fuel debris combines with groundwater and rainwater that seeps into the reactor structures and becomes highly contaminated. An average of 100 tons of such water is generated every day.

TEPCO has been filtering out most of the radioactive substances, but it is difficult to remove the hydrogen isotope tritium. The tritium found in the treated water also exists in natural sources of water including rainwater and seawater, as well as in tap water. Water that includes tritium is generated at nuclear power plants operating normally. Various countries have regulations setting out the concentration of tritium allowed in any water released into the sea, a practice that is common in nations with nuclear-power facilities.

The Japanese government decided on a plan for TEPCO to dilute the water stored at the plant before releasing it into the ocean. The water will be diluted until the concentration of tritium is less than 1/40th of the level set in national regulations, and about 1/7th the maximum level recommended by the World Health Organization for drinking. Currently, the plant has more than 1,000 storage tanks. They are expected to soon reach capacity.

In January 2023, a plan to begin the discharge sometime between the spring and summer of this year was decided upon. The construction of undersea tunnels to release the water began last year.

But local fishers are worried about possible damage to the reputation of their industry.

The Japanese government says it will not dispose of anything from the crippled plant without the consensus of all affected parties. A public education campaign is underway, involving television and newspaper advertisements, to explain that the water release is safe. It is also setting up a fund to help the fishing industry.

Reputational damage

Since the nuclear accident, farmers and the fish industry have faced deep suspicion from consumers even though their products meet national safety standards. Tourism businesses have also been damaged. Local officials are gearing up for a marketing campaign to promote Fukushima grown food globally.

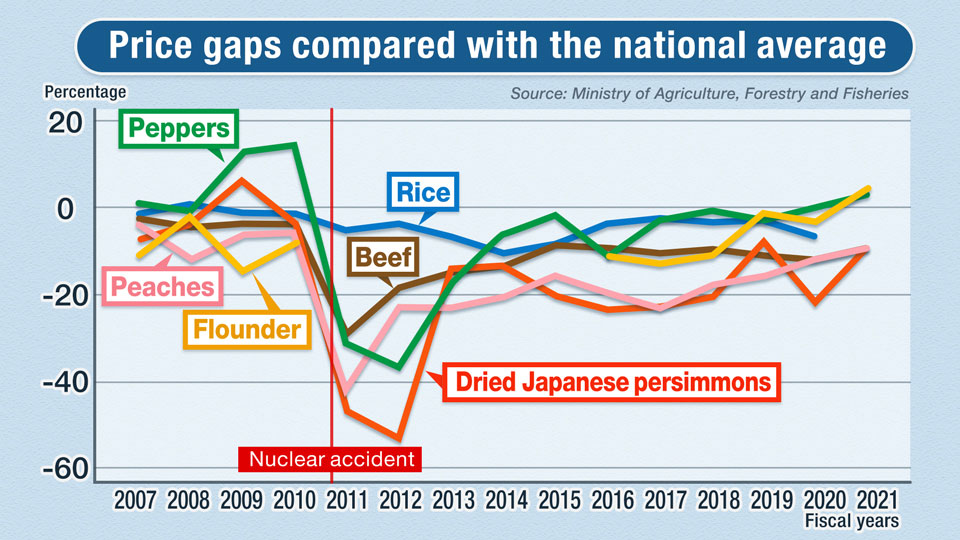

The Japanese government regularly publishes price fluctuations for six key food items: rice, beef, peaches, partially dried Japanese persimmons, peppers and flatfish, based on information from Tokyo's wholesale market. The data showed those prices plummeted for produce from Fukushima immediately after the nuclear accident. The price of persimmons from the area dropped to less than half the national average. And the price of Fukushima peaches dropped by more than 40 percent.

Two years ago, the price of flatfish and pepper from Fukushima rose to the national average for the first time after the accident. But other items still continue to be 10 or 20 percent lower.

Fukushima officials are working hard to repair the damage to the prefecture's reputation. They conduct thorough tests of radioactive products in food, including rice harvested from 10 municipalities around the plant, and randomly test fish caught in waters off the coast.

Dismantling and decommissioning housing and land

The Japanese government is undertaking a project to both dismantle housing that is no longer habitable and decommission housing and land based on owner agreements and applications. It's part of efforts to reconstruct areas that were subject to evacuation orders. Officials say this can be effective at removing radiation.

By the end of 2022, Japan's environment ministry had successfully dismantled roughly 17,380 buildings — more than 96 percent of all applications.

Decommissioning work entails removing radioactive materials from living spaces by removing earth and plants, covering with soil, or sweeping roofs and walls of buildings. The long-term objective is decreasing exposure to less than 1 millisievert a year, which experts say is not harmful.

The Japanese government started decommissioning work in Fukushima Prefecture soon after the accident, removing surface earth, washing roads and roofs, and cutting down greenery. Bags of radioactive waste were piled high in temporary storage spaces dotted throughout the prefecture. In some instances, the bags were temporarily stored on school grounds, in parks, parking lots, and even the gardens of private homes. The work was conducted at 44 of 59 municipalities and continues in zones designated "difficult-to return."

Much of the radioactive waste has been sent to an interim storage facility covering 1,600 hectares straddling the towns of Okuma and Futaba, which host the plant. Inside the facility, plants and combustible materials are turned into ash. Soil, stones and gravel are removed and stored elsewhere. That waste must be ultimately disposed of outside Fukushima Prefecture, as part of the terms of a deal signed with the environment ministry and officials of Okuma and Futaba and Fukushima Prefecture in return for their agreeing to the construction of the interim storage facility in response to a request from the ministry.

The environment ministry has laid out a plan to repurpose the soil for a multitude of public works and other uses throughout Japan, but only once the concentration of radioactive materials contained within the soil meets the national standard. Three-quarters of the stored soil is already below that level. The remaining quarter will be reduced in volume, brought outside the prefecture and disposed of permanently.

The ministry experimented with using the soil to elevate land and for growing vegetables in locations within Fukushima. Outside the prefecture, the ministry demonstrated that the amount of radiation was not problematic by placing planters containing such soil at the entrance of a ministry building in Tokyo. In December 2022, ministry officials announced they would conduct experimental projects outside the prefecture as the safety was confirmed through its activities in Fukushima Prefecture.

The experiments will be carried out at three locations related to the environment ministry. Meetings were held to explain to local residents, but people raised concerns about safety.

Public still skeptical

Residents of Okuma and Futaba made the tough decision to accept an interim storage facility. The Japanese government has promised more than 2,300 landowners there that it will dispose of the waste permanently outside the prefecture by March 2045. But people elsewhere have been refusing to countenance even test projects, and that's raising doubts within Fukushima about whether the national government will be able to deliver on its promises.

The central government is hoping scientific evidence will help sway public opinion, but there are few signs of that working so far.