Magnitude 9.0 quake

On March 11, 2011, at 2:46 p.m., a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck off the coast of northeastern Japan. Tsunami waves more than 10-meters high hit the coast of the Tohoku and Kanto regions, destroying more than 120,000 buildings.

According to the National Police Agency, the death toll, including missing persons, stands at 22,215.

Nuclear disaster

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, operated by Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), lost power due to flooding from the tsunami. That triggered meltdowns in three reactors. Melted fuel remains in the reactors to this day, which requires cooling with water.

The disaster was classified a level seven on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale, and as such is regarded as one of the worst accidents in the history of nuclear power.

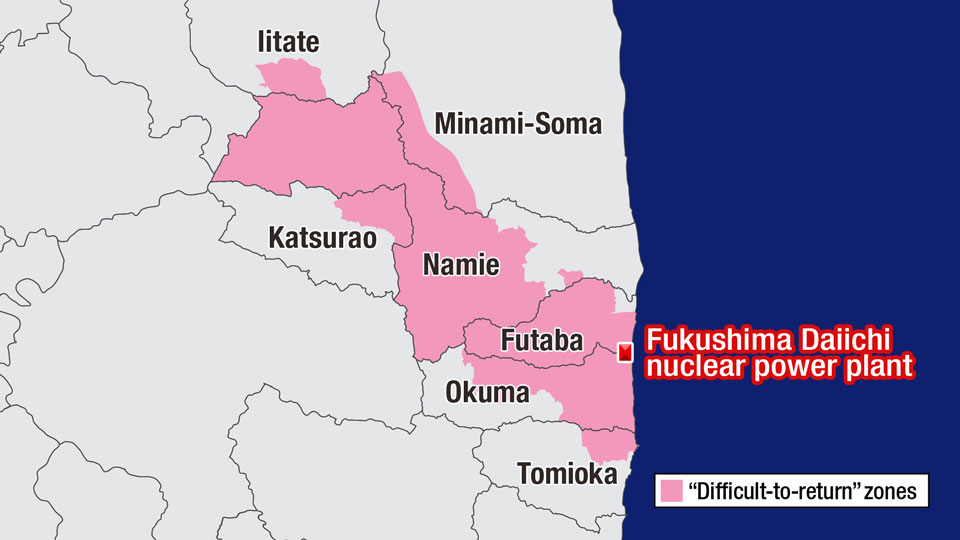

In Fukushima, evacuation orders were issued for 12 municipalities surrounding the nuclear plant, affecting almost 165,000 people.

Lives upended

Many people's lives were upended and local industries destroyed. Access to some of the zones classified "difficult-to-return" in relatively high radiation areas remains strictly limited. Those areas are in parts of the towns of Minami-Soma, Futaba, Okuma, Namie, Tomioka, and the villages of Katsurao and Iitate.

Decontamination work and the rebuilding of essential infrastructure continue to enable evacuation orders to be lifted, allowing some evacuees to return to their hometowns. Evacuation orders were lifted last year in some parts of Katsurao, Okuma and Futaba. This year, some parts of Namie, Tomioka and Iitate are expected to open up.

More disaster-related deaths than direct fatalities

According to the Fukushima prefectural government, disaster-related deaths in the prefecture totaled 2,335 as of November 2022. That is about 1.5 times the number of immediate fatalities caused by the disaster.

The disaster-related death toll includes people who became sick or whose diseases deteriorated due to prolonged evacuation, frequent moves, or unsurmountable disruptions to their lives caused by the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident. Municipal officers assess and confirm the cases based on applications submitted by bereaved families. Suicides are sometimes included.

The neighboring prefectures of Miyagi and Iwate have respectively reported 930, and 470 disaster-related deaths. Fukushima's figure is comparatively high because it includes many evacuees who have died over a long period. Over the last year, four deaths were added to the official record.

Many of the disaster-related deaths in Fukushima have occurred among evacuees living in municipalities along a coastal area that hosts the nuclear plant.

Evacuees resettle

Fukushima evacuees ended up in temporary housing, rentals, or relied on friends and family for somewhere to stay. As the environment has improved, the number of evacuees is decreasing as people return to their homes, rebuild in a different location, or take up residence in public housing built especially for disaster victims who lost their homes or were forced to evacuate.

Six years after the disaster, the number of evacuees halved. As of November 2022, there were 27,789 evacuees, or 16.9 percent of the peak number. Of the 27,789 remaining evacuees, 6,392 are within Fukushima Prefecture, and 21,392 are in other parts of Japan — including 2,392 in Tokyo. There are five people whose whereabouts are unknown.

But the Fukushima prefectural government regards the provision of temporary housing to evacuees as the end of their evacuation, and people who afterward enter disaster public housing are not counted as evacuees anymore. Some of these people still consider themselves to be evacuees though, so the figures announced by municipal governments don't always account for this.

Dying alone

As of January 1, 2023, there were 8,085 disaster public housing dwellings in Fukushima. The occupation rate remains high, with 7,073 in use.

But in a tragic note, some of those residents have died at home, alone. NHK research has found that as the coronavirus pandemic took hold during 2020, about 20 sole occupants passed away. Last year, there were 16 such deaths.

These deaths came as some residents grew increasingly isolated due to social restrictions implemented during the pandemic. Authorities are trying to find ways to encourage a better sense of community within the new housing developments.

Releasing treated water

A controversial plan to release treated and diluted water from the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant into the ocean is set to begin this spring or summer. The construction of undersea tunnels to release the water started last year.

Water is being used to cool molten fuel in the reactors that melted down in the disaster. It mixes with rain and groundwater that's seeped into the damaged reactor buildings and is contaminated with radioactive materials. About 100 tons accumulates each day.

TEPCO has been treating it by filtering out most of the radioactive substances. But it can't remove the hydrogen isotope tritium.

The Japanese government says the water will be diluted to lower the concentration of tritium to less than one-40th the level set in national regulations, which amounts to about one-seventh of the level the World Health Organization suggests for drinking water.

But some people, including local fishing industries, remain strongly opposed, with concerns over possible reputational damage from the water release.

More than 1,000 storage tanks at the plant are now almost full of treated water. They are expected to hit capacity this fall.

The Japanese government says it will not dispose of anything from the crippled plant without consensus from all affected parties. It has a public education campaign underway, involving television and newspaper advertisements, to explain that it is safe to release the treated and diluted water. It is also setting up a fund to help the fishing industry.

The focus now is on whether or not a consensus can be reached.

*The second installment, focusing on nuclear disasters, will be published shortly.