Beds – just not for COVID-19

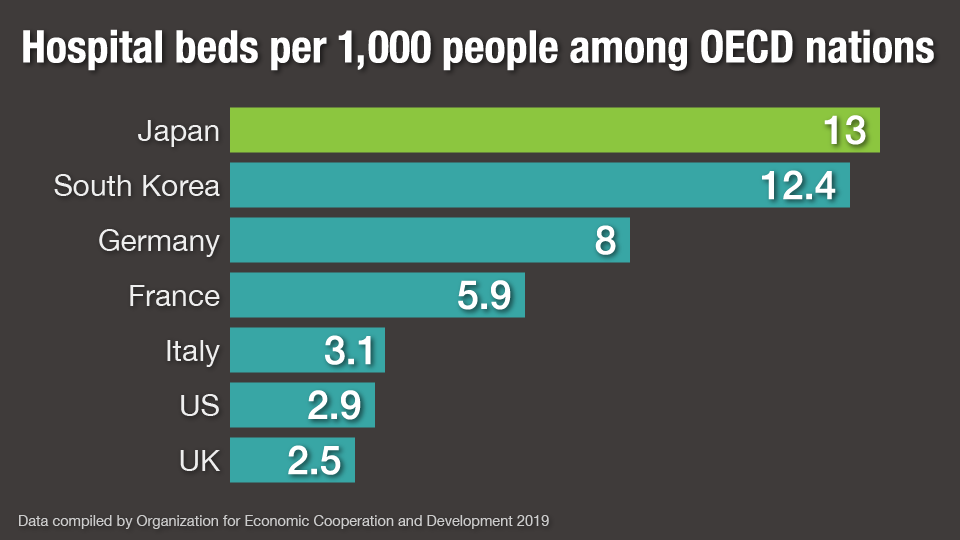

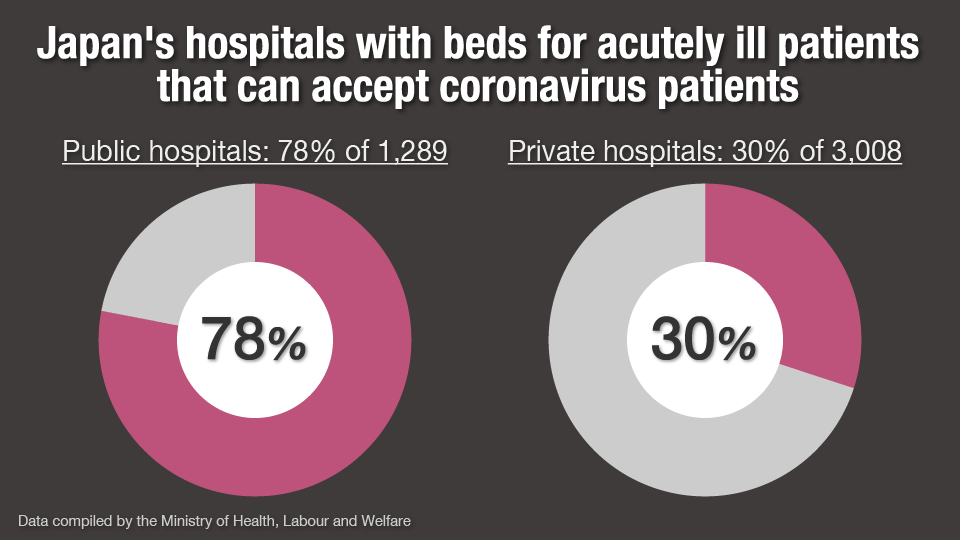

On the surface, Japan looks relatively well-equipped to cope. As of 2019, it had the most hospital beds per 1,000 people among all 37 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. But a closer look paints a different picture. As of January 10, the health ministry said 78 percent of public hospitals with beds for acutely ill patients could accept coronavirus patients, but only 30 percent of private hospitals, leading to calls that they should be taking in more.

Mano Toshiki, a medical doctor and professor at Chuo University, says about 80 percent of Japan's hospitals are small or midsized private entities with limited human resources. The problem is two-fold: few personnel can treat coronavirus patients, and the anti-virus measures taken at the facilities are often short of the mark.

Designed for the elderly, not the pandemic

Mano also points out that among the OECD nations, Japan's inpatients stay in hospital the longest: 16.1 days on average, compared to just over 5.5 days in the United States.

"Our medical system is highly accessible, and we can receive treatment for a long time. It's suited to chronically sick patients, such as those with cancer, a brain stroke, or lifestyle-related illnesses suffered by the elderly," he says.

But Mano also says resources have been spread thin. "Dealing with coronavirus patients has been difficult for these hospitals. We should have consolidated, so that the system can better handle the coronavirus. For example, by setting up specialized facilities before the third wave of infections arrived this winter.

Japanese Red Cross Musashino Hospital, a public entity in Tokyo, has been accepting seriously ill coronavirus patients since the beginning of the pandemic. A surge in infections last December pushed it close to capacity, but the hospital still accepted more patients in the hope that private hospitals would do the same.

The hospital increased the number of beds for seriously ill patients from five to six, and for moderate cases from 40 to 58. Even moderate patients require 1.5 times as many nurses as typical forms of care, while severely ill patients require three times as many.

The hospital has recently received more coronavirus patients with complications, such as severe pneumonia and liver disease. It's been left with no choice but to draft in doctors and nurses from departments that provide other forms of care – ultimately affecting the overall ability to treat people. At the peak of the third wave of infections in January, the hospital was able to accept only around 80 percent of the emergency patients who arrived. It was also forced to postpone surgeries.

"We've been taking in five new coronavirus patients a day due to requests from other hospitals that are struggling to treat seriously ill or nearly seriously ill cases," says Izumi Namiki, the director of the hospital.

"Our doctors do their utmost to keep on working despite the shortage of staff, but we're worn out," he continues. "It's impossible to increase the number of beds any further. What's more, preventive measures cost a lot. The more patients we accept, the more we fall into the red."

The director says few private hospitals in the region accept coronavirus patients, though they have artificial respirators. "This is an emergency. I want medical facilities that are able to provide intensive care to start accepting coronavirus patients. I want those that specialize in recuperation to start accepting recovering coronavirus patients. We must make the fullest possible use of medical resources in the region."

Private hospitals also feel the strain

Minamitama Hospital, a private facility with 170 beds in Hachioji, western Tokyo, has been accepting coronavirus patients since February 2020. It has closed its pediatric ward to provide 23 beds for moderate and suspected cases. All were full at the peak of the third wave of infections in January 2021.

The problem is compounded by the fact that the pandemic makes it difficult for elderly coronavirus patients or people with pre-existing conditions to transfer to other hospitals, even after recovering. Some hospital owners are concerned transferred patients could infect other non-coronavirus patients even if they have recovered. Also, a possible cluster infection could affect business and the hospital would have to temporarily suspend admissions.

Mashiko Kunihiro, the director of the hospital, says: "I understand that hospital owners want to avoid excess pressure on their facilities after having to handle difficult situations such as being criticized over cluster infections and decreasing revenues. But, unless all medical institutions join forces in the battle, we can't handle the coronavirus. Even if there are gaps in hospitals' ability I want other places to accept these patients."

Need to share roles of hospitals

Though Japan's vaccination drive is underway, experts say it will take a long time to reach "herd immunity."

Mano says hospitals should cooperate to provide treatment according to their size or speciality. He says many of Japan's small or midsized private hospitals were established by expanding small clinics, and they will find it difficult to classify space, but they can handle coronavirus patients whose condition settled.

"Local governments and medical associations should create a role-sharing system between hospitals in the region, with private hospitals supporting public hospitals that take care of coronavirus patients on the front line."