It's immediately apparent that this tour is very different from the countless others that operate throughout Japan. When participants gather at Tokyo Station early in the morning, they are each given a dosimeter, allowing them to track the radiation levels on the way north to Fukushima. The tour operator says the idea behind this is to show the guests that the radiation levels are controlled and safe.

The tour attracts people from around the world who are keen to learn about life after the nuclear accident. John Ericson, who is visiting from the United States, says he heard a lot about Fukushima over the years and wanted to see for himself what things were like.

Martin Brandt, from Germany, says he was interested in seeing the aftermath of the disaster because what happened in Fukushima led to a complete change in his own country's nuclear energy policy.

Fumie Endo, a Fukushima native and one of the guides who leads the tour, says the goal is to dispel misconceptions about the prefecture. She says she tells the guests at the beginning of each tour that "Fukushima is not all the same."

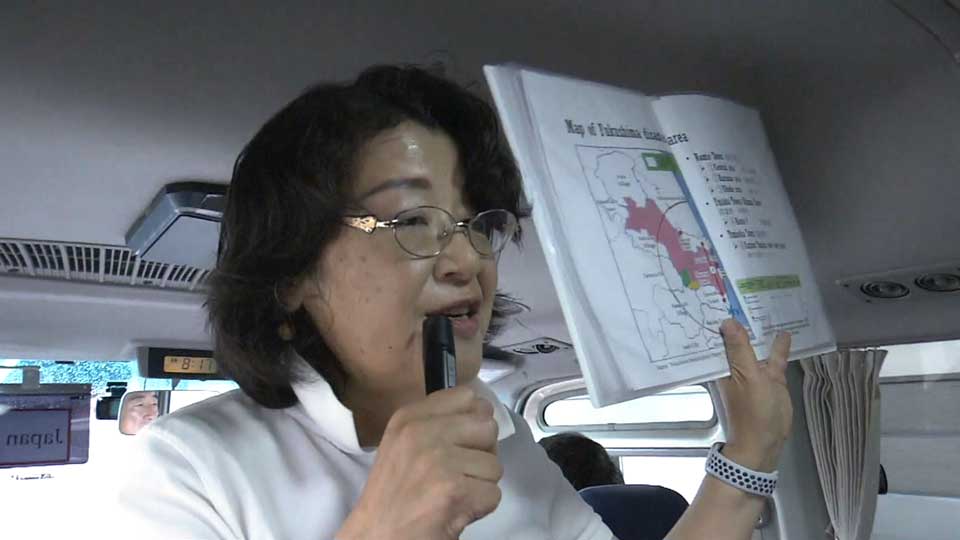

"When we say Fukushima," she says, showing the tour a map of the prefecture, "we have to remember that this is the name of the prefecture, the name of the city, and the name of the nuclear power plant. It's all different."

Even though almost a decade has passed since the disaster, the prefecture still faces stigma based on what happened. Some people believe that the entire prefecture is contaminated and are hesitant to visit or purchase its products, despite the ample safety checks.

Fumito Sasaki, who runs the company that operates the tour, decided that something had to be done. He thought a tour would be a good way to educate people about the prefecture. In 2017, he started the "Fukushima disaster area tour," a name he thought would help attract people who search the internet with the words "Fukushima" and "disaster."

So far, the tour has taken more than 700 visitors to Fukushima, with the support of government subsidies.

Sasaki says the tour means more than just business for him. His wife was born and raised in the prefecture, while his father hails from neighboring Miyagi, which was also devastated by the earthquake and tsunami. He says the fact that the area has a negative connotation for many foreigners is heartbreaking.

"When they hear the word 'Fukushima,' they think the whole prefecture is dangerous," Sasaki says. "It's important to make sure our clients understand it's only a small part."

The tour visits communities within a 20-kilometer radius of the crippled nuclear plant. In the town of Namie, where all residents were ordered to evacuate the day after the accident, it's as if time has stopped. At a school, children shoes remain as they were at the time, inside cubbyholes in the lobby. A pub that was once filled with laughter is deserted. Tour participants see the remnants of lives that were suddenly shattered.

"It's sad to see the dramatic changes to the lives of the people," says Axel Meiling, from Germany.

The tour also provides the chance to meet with local residents.

Masami Yoshizawa, a cattle farmer at the Ranch of Hope Fukushima, tells the participants that he keeps 254 cows he can never sell because of contamination. During the disaster, many cows in the town starved to death after everyone evacuated. The government told the farmers to kill the ones that survived. But Yoshizawa refused. He says they're his friends and also living reminders of how life can be upended at any moment.

"I'll keep them until they die," he says. "I know it's not economical and it may be silly. But I'm determined to live with these cows. I am, and always will be, a cattle farmer."

The tour participants also see signs of recovery. Residents have been returning to parts of the town where the evacuation order has been lifted. Businesses are reopening at a small shopping mall near the town hall.

The tour happens to run into Daisuke Suzuki, the owner of an old sake brewery, which had been operating since the 19th century. But it was located in the coastal part of town and was washed away by the tsunami. Then afterwards, it was unable to reopen as it was located just seven kilometers from the plant, well within the evacuation zone. Suzuki continues to brew sake outside of the prefecture. He tells the tour that he plans to return to his hometown next year.

For the participants, seeing both the damage and the recovery has given them new perspectives on Fukushima.

Hannah Foley, from the United States, says she now has a better understanding of the extent of the devastation and feels that something like it can never happen again. Pete Harvey, from the UK, says he was struck by how the people here don't seem to be dwelling in the past, and are trying to get their lives back together.

Fumito Sasaki says he believes tourism can play a crucial role in revitalizing the region.

"I think the hope is there, in how people have hung on," he says. "We want to show visitors this hope. And bringing more people will also give residents the motivation to restore their communities."

Many of the participants say they want to visit the area again, perhaps in 10 or 20 years, to see how things have changed. In the meantime, residents say they will keep working, so that visitors get to see communities that are even stronger than they were before the disaster.