But this solution has created a new problem from Izumo. While their parents are at work, the children of these laborers have found it difficult to settle into life in Japan. Many struggle at school and are unable to find work, and say the city and the prefecture have not done enough to create a support system.

"I couldn't make any friends."

16-year-old Alexia Misutsu moved to Japan from Brazil five years ago when her parents were hired by a factory in Izumo. The Misutsus are one of thousands of Brazilian families who have followed work opportunities to Shimane in recent years. The prefecture's Brazilian population has tripled since 2013, standing at about 3,000 as of the end of last year.

Alexia says she has not been able to adjust to life in her new home because of her limited Japanese, and, after graduating from junior high school, she abandoned the hope of further education.

"I couldn't make any friends because I didn't understand Japanese," she says. "It was hard. This experience is why I didn't go to high school."

"I needed support."

Alexia decided to get a job instead. But she found work just as difficult as school.

She spent more than a year hopping around part-time jobs, unable to settle at any of them. Eventually, thanks to guidance from the Izumo City office and a non-profit organization that supports Brazilians in Japan, she was able to get a position at a nursery. She has finally found a place in Japan where she feels like she belongs. She has now started studying Japanese, with the goal of becoming a certified nurse.

"I needed support when I first arrived, when I was in a bad place," she says. "Most foreigners need help because we don't know the language or the culture."

Staying at home

Yumi Goubara teaches at a Japanese language school in Izumo. Three years ago, she set up a volunteer group called Manabiya to teach Japanese to young foreigners.

"These days, there are an increasing number of foreign children and young people in the city who are shutting themselves in at home," she says. "For many of them, the only reason they give up on education is because they moved to Japan. I think the most important thing is to let them know that people care about them and about their futures."

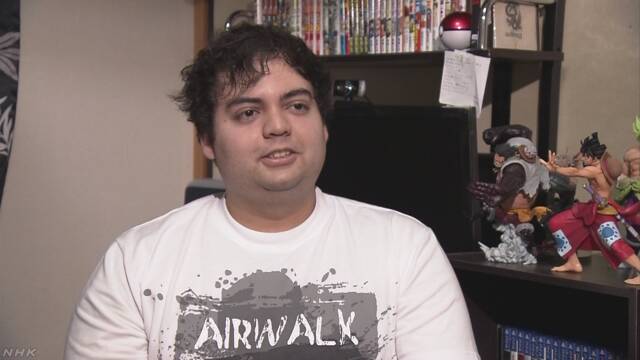

21-year-old Lopes Renan is one of the young people supported by Goubara's group. He moved to Izumo with his parents when he was 15, the age at which high school starts in the Japanese educational system. But he decided not to enroll because he believed his Japanese was not strong enough.

Back in Brazil, he had been an excellent student and was studying computer programming at a technical school. His dream was to work as a video game designer. But he quickly abandoned these hopes when he moved to Japan.

"I didn't know where I could go to continue studying," he says. "The only reason was because I didn't understand Japanese. At the time, I really regretted having come here."

For three years, Lopes rarely left his home. He lost the will to study or work. He spend most of his time watching anime and reading comic books. In a sadly ironic twist, he says this actually helped him learn Japanese but since he didn't go out and meet people, he never used it and was unable to get used to speaking.

Opening up

Renan says meeting Goubara helped him reintegrate into society. Manabiya, the volunteer group, places an emphasis on making young foreigners feel comfortable about sharing their worries. Goubara says this is important, and not just as a way to learn Japanese.

Little by little, Renan started opening up to the group, talking about his anxieties. He says this process allowed him to feel relaxed enough in social situations to start looking for work. On Goubara's advice, he took a part-time position at a convenience store. He is now also working at a factory producing computers and tablets.

Renan says he's still not sure what he wants to do. But he has some ideas of what his future could look like. One possibility is managing a cafe for video game-lovers like himself. Or maybe resuming his computer programming studies.

Lost potential

The Japanese government is planning to increase the country's foreign workforce in the years to come, largely as a way to help cities like Izumo. However, if nothing is done to improve the system, cases like Alexia's and Renan's will only continue to emerge.

"Living abroad should be a way for young people to widen their horizons and experience new things," Goubara says. "Instead, they are coming here and we are wasting their potential. It would be tragic if this continued."