The question of why Imperial Japan launched these attacks has been one of the enduring mysteries of the country's role in the war. However, new research shows they may have been the result of a thorough, albeit misguided, analysis that pointed to a need for a desperate gamble.

Recently, a group of researchers undertook the task of piecing together an army report produced before the start of the war. Compiled by leading Japanese economists, the report attempted to analyze the relative military strength of major countries at the time, including the US and Britain.

The report went against the current of nationalistic confidence that was sweeping the military at the time, portraying the likelihood of Japan's success in starkly realistic terms. For this reason, historians believed it was destroyed long ago.

But the researchers were able to track down fragments, finding scattered documents in university libraries and secondhand bookstores. The complete version is now kept at the library of the Faculty of Economics at the University of Tokyo.

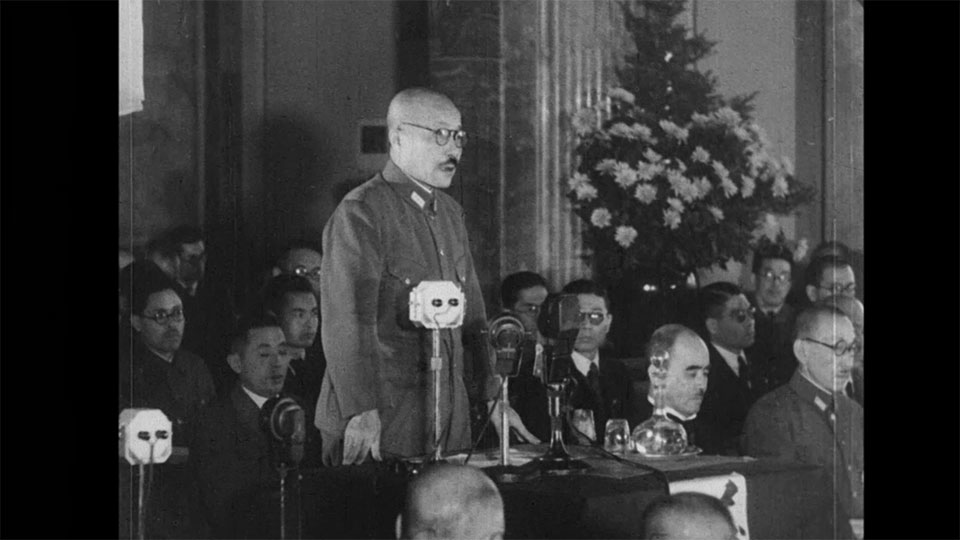

The group that drew up the original report was known as the Akimaru Organization, named after Lieutenant Colonel Jiro Akimaru, who led the team.

In a 1991 interview about decision-making leading up to the war, Akimaru said that even within the military, it was accepted that the US and Britain were much stronger than Japan. But no one was willing to say this out loud to the top officials.

"Attacking the US and Britain meant confronting countries that were a combined 20 times more powerful," he said. "But this was a time when negative opinions could not be expressed."

Kuniaki Makino is an associate professor at Setsunan University in Osaka. He has been examining the report's evaluations of the US and Britain. He says both sections highlight how factors such as oil production and ship-building made the countries far stronger than Japan. But he says the analysis of the military supply routes between the two countries is particularly insightful about what drove the thinking at the top levels of the Imperial Army.

The analysis suggests Japan could triumph in a war against Britain if Germany were able to quickly defeat the Soviet Union and gain control of Europe. German ascendancy on the continent would cut off the flow of supplies from the US, making Britain less likely to extend itself fighting Japan halfway across the world. Makino says the Imperial Army leadership saw this as a weakness that could be exploited, and used it as justification to go to war.

"Even if the actual intention was to avoid starting a war, the conclusion of the report was deliberately ambiguous," Makino says. "It was drafted by a department of the army ministry, so obviously it couldn't contradict established policy."

Makino has been attempting to evaluate the decision to attack the US and Britain from an economic standpoint, using what is known as Prospect Theory. The principle posits that a person in distress has two choices. The first is to take a gradual approach to try to ease the situation. The second, which is what most people tend to opt for, is to try to quickly eliminate all problems in one go, despite slim chances of success.

Makino argues that this is what Japan chose. The country's position of dominance in Asia was threatened because of US oil embargoes. The situation was likely to force Japan to cede to the US within a matter of years, with or without a war. Faced with this predicament, a fanciful idea settled in among Japanese leadership: the belief that all of these problems could be erased by war.

The thinking went that if Germany cut off shipments between North America and Europe, while Japan occupied Southeast Asia and secured the region's resources, Britain would be forced to quickly surrender, and the US would lose its appetite for war.

Despite the immense odds, the risk seemed worth it to the Japanese leadership. Makino says that rampant anti-US sentiment within the country added to the Imperial Army's inclination to opt for a more radical approach, which in turn colored its interpretation of the Akimaru report's analysis.

"Being in possession of accurate information does not necessarily mean the right decision will be made," Makino says. "By simply focusing on part of the report, it was interpreted as acceptable to start a war. Information can be used for the wrong ends."

Japan's road to war has long been characterized as the result of mindless nationalistic posturing by military decision-makers who knew there was no hope for success. But the Akimaru report suggests the leaders actually adopted a strategy which they thought could shift the global situation in Japan's favor.

Countries continue to use accurate information to make bad decisions. This highlights the need to study history and learn from past mistakes. Of course, part of this is so we can hold individuals and organizations responsible. But by analyzing how Japan justified its attacks on the US and Britain, we can better understand the thinking that supports the decision-making that continues to this day.