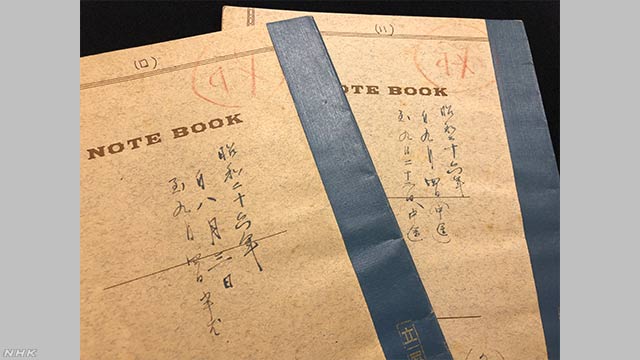

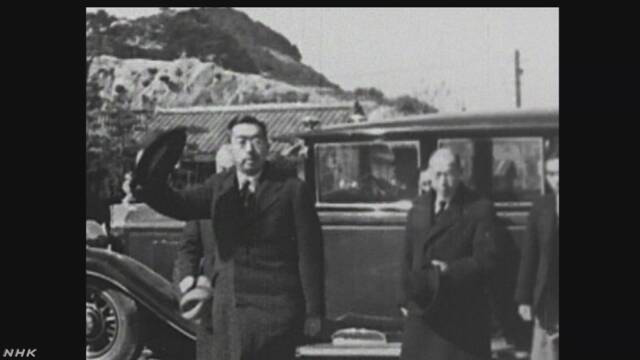

The Emperor, also known by his given name Hirohito, particularly wanted to speak of his remorse in an address at a 1952 ceremony to mark the restoration of independence in Japan. The revelations are part of the personal records of the first Grand Steward of the Imperial Household Agency, Michiji Tajima.

Tajima, who served for five and a half years under the postwar Constitution, beginning in 1948, kept detailed notes of his audiences with Emperor Showa between February 1949 and December 1953.

The documents reveal a peek behind the curtain into one of the most shrouded monarchies in modern times - and offer new insights into the mindset of both the Emperor and the prime minister at a critical moment of change for the country.

"Emperor Showa had not articulated his regret and remorse in public during his lifetime, so it is a surprise that he would speak of such a deep sense of regret," says Nihon University professor Takahisa Furukawa, an expert on Japanese modern history and one of the academics who analyzed the records.

Furukawa adds the records will be a "first-class reference material" for historians studying the Showa era, which lasted from 1926 to 1989.

In the lead-up to the Emperor’s pivotal address in May 1952, Tajima wrote that the Emperor wanted to share with the public his sorrow over Japan’s role in the war.

On Jan. 11, 1952, he told Tajima he "definitely, definitely wanted to include the word ‘remorse’ in the address." The next month, he said, "Talking about remorse, I do have many things to be remorseful about."

In detailed records of the speech drafting process, Tajima outlines the Emperor’s belief that everyone in Japan should "search our souls so we won’t go through the same situation again," referring to the war in the Pacific theater.

"The military, the government, the public - they all have things to feel remorse for, such as overlooking the military’s arbitrary actions," the Emperor told Tajima on Feb. 20, 1952.

The leading role of Japan’s military in pursuing war is one that the Emperor continued to come back to in his conversations with Tajima. He described the military’s actions as "supplanting" that of the government’s, and according to Tajima, regretted his failure to keep the military in line.

"In retrospect, the act of supplanting should have been eradicated quickly," he said. "No one could stop the momentum the military had...by the time Hideki Tojo became prime minister in Oct. 1941, the situation was too grave to do anything."

Throughout a months-long draft process, Tajima and the Emperor worked closely together to come up with a speech reflecting the Emperor’s true thoughts. After the Imperial Household Agency removed the word "remorse" from the draft, the Emperor pushed back in a meeting with Tajima on Feb. 26.

"I really want to include remorse for the past and self-discipline for the future, with different wording. Please revise again."

A week later, the Emperor was pleased with the new draft which included allusions to remorse, saying, "The parts about showing gratitude for people in Japan and abroad, sympathy for the war dead and remorse are good. I hope the Cabinet will not change the text much."

After meeting with then-Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, Tajima had good news to report back to the Emperor. "I asked the Prime Minister not to change the text much, and he gave his consent."

Tajima wrote that Yoshida thought the draft speech was "good overall" but he wanted the Emperor to "express the ideal of a new Japan more actively and strongly."

At this point, less than a decade after the end of the war, Japan was a country at a crossroads - facing a new future and figuring out what role it would play on the international stage.

For the Emperor, his vision of a new Japan was a modern one.

"I don’t think Japan should remain old-fashioned," he told Tajima on March 6, 1952, adding that he wanted to deliver his address over the radio regardless of whether the ceremony was held, and asking Tajima to do thorough research on that possibility.

But the Emperor’s forward-thinking vision ran up against roadblocks in the Imperial Household Agency, with senior officials deleting the phrase "against my will" - a line intended to show that the Emperor hadn’t wanted war, because "it didn’t sound nice," Tajima wrote.

Emperor Showa wasn’t happy with the deletion, asking Tajima, "why does it not sound nice? What’s wrong with saying that? That’s how I think, so I think we should keep the phrase."

In a back and forth between the Emperor and the government, with Tajima acting as the go-between, the Emperor doubled down on his anti-war stance.

"I had clearly told [then-Prime Minister Hideki] Tojo at the time that it is truly a pity to part ways with Britain and the United States," he told Tajima, referring to the time leading up to Japan’s declaration of war on the US and Great Britain on Dec. 8, 1941.

"Your Majesty may say that it was against your will, but in the end, you did declare war under the reasons written in the Imperial edict, which bears your name and seal," Tajima reminded him. "Since it was Your Majesty who had declared war, at least on the surface, one might argue that His Majesty need not have done so if it went against his will."

According to Tajima’s records, government officials worried that the Emperor would sound like he was making an excuse. The phrase "against my will" was replaced with "as momentum went."

But the draft speech still underwent further changes in the bumpy road leading up to the ceremony. Just 15 days before the Emperor was due to deliver the address, Tajima reported to the Emperor that the prime minister wanted the entire passage expressing regret removed.

"Yoshida is worried that calls for the Emperor’s abdication, which had at last subsided, could reignite, and that he would rather not hear the Emperor mention ‘war’ or ‘defeat’ at this time," Tajima said, adding that the government was concerned that expressing regret would raise "the danger of inviting arguments that the Emperor is responsible for starting the war."

After taking three days to think about it, the Emperor told Tajima on April 21, "I’ve been contemplating the issue since we last met...I’ve been telling foreign people such things all the time, so I don’t see anything wrong...but if the prime minister feels troubled, it cannot be helped, although I am not happy."

But despite his outward acknowledgment of the prime minister’s viewpoint, the Emperor was "quite straightforward in expressing his dissatisfaction today," Tajima wrote. He also didn’t agree with Yoshida that avoiding references to war or defeat was the best way to "address the bright future ahead" for the country.

The Emperor, "looking displeased," asked, "but then how do you not mention war and still lead the speech to remorse?"

As the day of the address loomed closer, Tajima wrote of speaking with the Emperor of the high stakes facing the government.

"The speech, in reality, will be hugely relevant to national politics," he said on April 22. "Your Majesty’s phrase that the war was against his will, and the specific mentions of war, defeat and devastation...it may sound like an excuse to say that the result of the war was against national principle or the Emperor’s will, and people might misunderstand that the Emperor, after waging war, is now trying to look like a pacifist."

In the end, Tajima said, the celebratory nature of the ceremony called for a "more suitable" speech "expressing the joy of independence and looking ahead to the future. It may be better to avoid making specific references to the war."

He apologized for the "inconvenience and worries that he has caused so late, after listening to the Emperor’s thoughts for nearly a year."

In the end, the passage expressing his deep regret was dropped from the speech, with the Emperor acquiescing to the government’s wishes and accepting his role as the "symbol of the State" under the new post-war Constitution.

"Contrary to the Emperor’s wishes to settle the past, he had to live on with feelings of torment," says Professor Furukawa.

But the Emperor’s true feelings have now been immortalized in the newly revealed documents, Furukawa adds.

His son, the Emperor Emeritus, has spoken often of his own "deep remorse" for the war - a reflection, perhaps, of the changing times and growth of Japan’s emphasis on peace in the modern era.