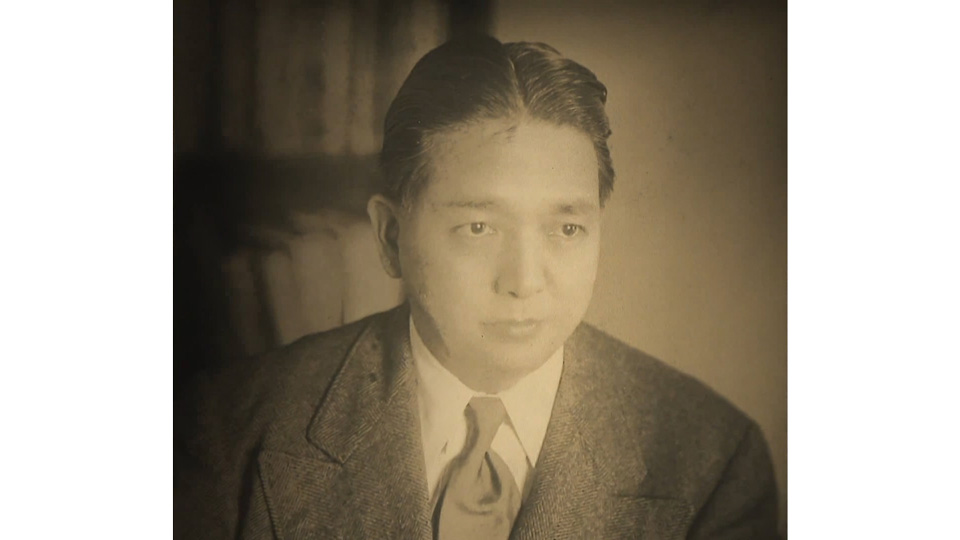

Yoshiaki Shimamoto always finds it painful to return to Hiroshima. He lost his parents and younger sister in the atomic bombing. At the time, he was away from the city. When he returned, he learned that his entire family had died at a temple from severe burns. Shimamoto says the day he went to the temple to retrieve their ashes was the saddest of his life.

"It wasn't until I held those three wooden boxes that I truly realized my family was gone," he says. "I understood it was true and had no choice but to accept it."

Shimamoto was nine years old, and suddenly found himself all alone. He was sent to an orphanage but he says it never felt like home. He was beaten and bullied. He says he felt completely isolated.

"People would say terrible things to me like, 'We're the only reason you're still alive, you orphan!' Hearing things like that was the hardest part."

But during this dark time, there was something that lifted his spirits: a series of letters from America.

"Dear Yoshiaki,

I was very happy to receive a picture of a good looking young boy and to help him in getting an education."

They were from Vicki Zaser, an Idaho-based radio host. She also sent packages and money. Zaser had enlisted as a "moral parent", one of hundreds of Americans taking part in a support system for Hiroshima orphans.

Shimamoto found new meaning in life through exchanges with his moral parent. He studied hard and made it through college, before going on to become a music teacher. This decision was also spurred by Zaser. Fond of music, he wrote to her and asked for a violin, which she duly sent.

Shimamoto says he was overjoyed when he opened his violin. From that point on, his love for music only grew.

"I was so happy to find there was someone in America who cared. Knowing someone was out there, helping me, gave me a lot of emotional strength".

The program, named "moral adoption", was the brainchild of Norman Cousins, a well-known young voice in American journalism. At the time, the US government justified the use of the atomic bombs as a way to quickly end the war and save American lives. But Cousins did not agree with this view.

Four years after the atomic bombing, Cousins visited Hiroshima. After meeting children at one of the city's largest orphanages, he thought of a way to help improve their lives. American citizens could become "moral parents" for the orphans, supporting them by sending letters and money. Approximately 600 people from across the US applied for the program. Some said they wanted to enroll because of a desire to atone in some way for the atrocity committed by their country.

During our research, we learned of someone who played a crucial role in inspiring Cousins to create the program but had been forgotten with time.

Kiyoshi Tanimoto was serving as a Christian minister in Hiroshima at the time of the bombing. His daughter Koko Kondo says that after the blast, her father rushed to the city center to find his family. On the way, he had to ignore many voices calling for help from under the rubble. This haunted him for the rest of his life and she says it motivated him to work to help survivors, especially children.

"I think he always had this feeling that he needed to do something for the children affected by the bomb," Kondo says. "He wanted to talk about what the bomb did and how the war had hurt so many innocent children."

In 1948, Tanimoto was invited to the US by the Methodist Church. Over the next 15 months, he traveled across the country, giving talks about the plight of the atomic bomb survivors. But it was not easy to get Americans to sympathize. Most believed the bombs were needed to end the war. Tanimoto tried to work through this by seeing things from their perspective. But this was not easy. A diary entry from the time reveals his sense of conflict:

"Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor started all the suffering, so it deserves an apology. But at the same time, Japan's suffering was many times greater than what America had experienced. When I think of this, I'm overwhelmed with emotion and feel great pain."

He struggled to reach his audience. But then came a helping hand. Through friends, he was able to meet the Nobel-Prize winning author Pearl S. Buck. Tanimoto was able to convince her to get involved.

"My biggest concern was helping the victims of the bombing. I knew I had no choice but to ask for assistance from Americans in order to accomplish this."

Buck was moved by his passion.

"The peace movement must be one with a firm grounding in love."

Buck used her personal connections to get prominent figures to support Tanimoto's cause, including Norman Cousins. Inspired by his meeting with Tanimoto, Cousins launched the moral adoption movement.

Tanimoto kept fighting for peace until his death in 1986. He never forgot about the orphans.

When asked what her father's goal in life was, Kondo had this to say: "Probably world peace. For everyone to live in harmony. He really hoped there would be peace in the world, that each and every one of us would be able to live together. He said that over and over again. It's difficult to change society and make politicians act. But he told me, Remember this Koko. One day, the hope passed on from one person to the next will lead to success."

More than seven decades later, the moral adoption program has been largely forgotten. The story of the war orphans--how many there were, how they lived--remains unclear.

One reason is that the government, amid the chaos of the immediate post-war period, did not conduct thorough surveys on their numbers. Many orphans lost without a trace. Another reason is that they did not speak about their identity. A the time, there was discrimination and prejudice against atomic bomb survivors, with groundless rumors spreading that they were sterile and contagious.

Historians and researchers across Japan are now feeling a sense of urgency. Many war orphans are in their 80s and time to talk to them ahead of the war's 75th anniversary is running out.

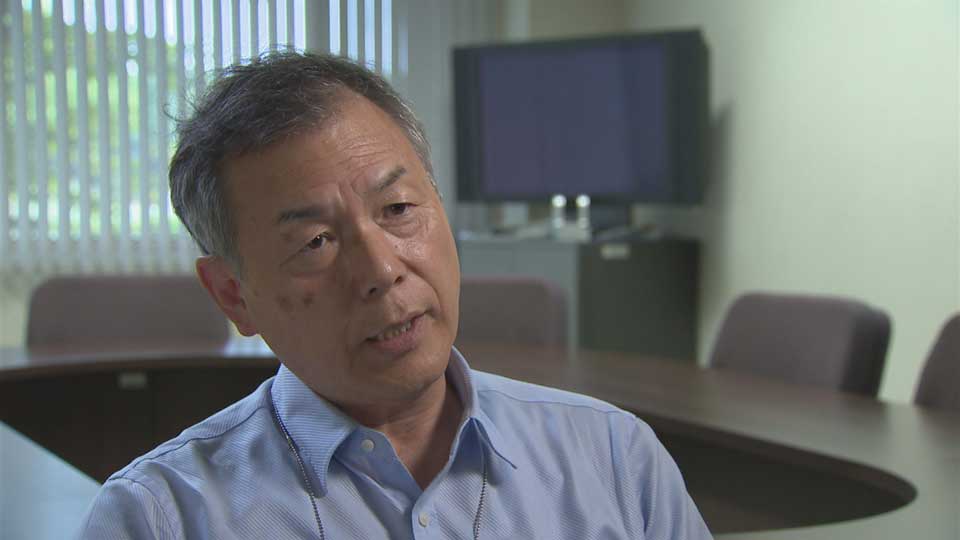

Haruo Asai, Professor Emeritus of Rikkyo Unversity, says he and a number of other researchers have agreed to collaborate on a series of three books to be published next year on how war orphans survived during the postwar era. Their research focuses on children orphaned by a range of causes: the atomic bomb, the Battle of Okinawa, the Tokyo air raids, among others. Asai says he hopes their work will be able to reach a large number of people through a combination of printed material and symposiums. Their work is considered a groundbreaking effort to clarify the story of the Japanese war orphans.

Asai says people talk lightly about the importance of life. But truly understanding this is only possible if we learn about a time when lives were not valued at all.

Children continue to be the victims of conflicts around the world. They should be the ones most protected by society but in reality, they are often left most vulnerable to conflict, poverty and abuse. The stories of the atomic bomb orphans are a urgent reminder for us that we need to do more to ensure that no more children suffer.