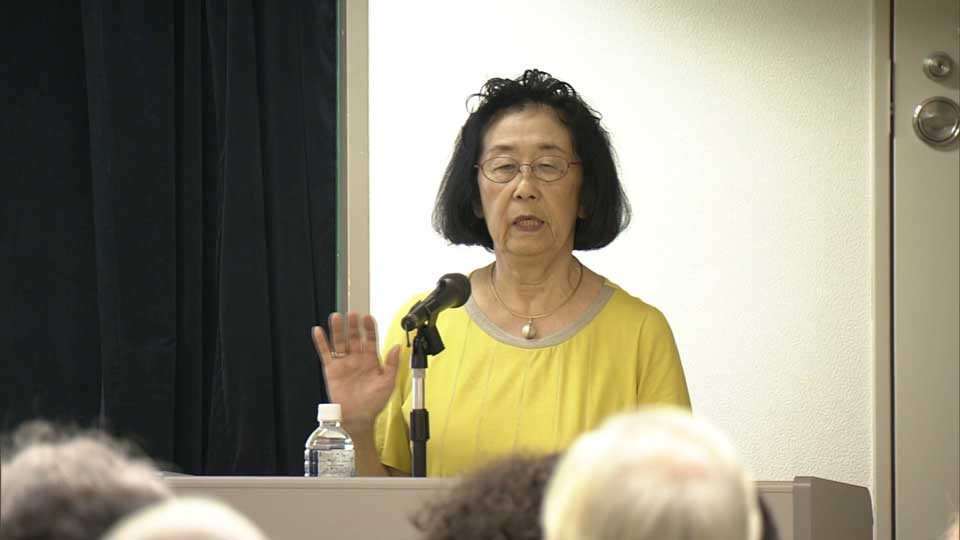

Suzuki's granddaughter Michiko was born in 1931 and was close to her grandfather. She has only recently started to tell his story.

She says many Japanese people today don't know about the war, so she wants to make sure everyone hears the truth about what happened.

Appointed the Prime Minister

Following repeated air raids, by April 1945 it was clear Japan was losing the war. That's when Kantaro Suzuki was appointed prime minister at the age of 77.

He had served as grand chamberlain to Emperor Showa, whose given name was Hirohito, who repeatedly asked Suzuki to become Prime Minister.

While Japan's defeat was inevitable, there was no easy way to end the war. Some in the military were determined not to give in, and were preparing for a decisive battle on the mainland. The government at the time struggled to control the most hawkish military leaders.

Michiko says the Emperor told her grandfather that it didn't matter if he was no good at politics, or was hard of hearing, because he was the only one who could handle the situation. She says her grandfather eventually agreed to take the role on.

Military hardliners

In the decades before World War Two, the military was increasing its power, ignoring the government and becoming an uncontrollable force. Suzuki knew that better than most people.

In 1936, he was attacked by young officers as part of an attempted coup. He was shot four times, including between the eyes, but miraculously survived.

"I remember it was snowing hard that day," says Michiko. "My brother and I were in bed with colds. The phone rang, and I heard that my grandfather was in critical condition, so my father rushed to the hospital."

Suzuki thought he had to bring the war to an end, though he knew it might lead to his death at the hands of his opponents.

Michiko says "Because he survived the attack, I think my grandfather felt strongly that he must sacrifice his life and not think about himself."

Plan for the end

During his time as prime minister, a devastating battle raged in Okinawa. Several months later, atomic bombs exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Still, some in the military wanted to push on, calling for the entire nation to carry out honorable suicide attacks, and to prepare for a decisive battle on the mainland.

When Suzuki took office, he gave a speech, saying: "First, I will lead the nation and die a noble death. The citizens must then move on and strive to break the deadlock of national difficulty."

But Suzuki indicated his readiness to play a key role in ending the war by comparing himself to another statesman. Michiko Suzuki remembers him saying he would be "like Badoglio."

Pietro Badoglio was a Prime Minister of Italy. He took office after the downfall of Benito Mussolini, and soon surrendered to the Allies.

"In Japan, people were saying Italy's defeat was Badoglio's fault," Michiko says. "Newspapers attacked him for being a traitor. But by citing Badoglio, my grandfather was telling our family that he intended to lead Japan in the same direction."

Suzuki had a secret plan to end the war. At an Imperial Council meeting on August 10th, he asked the Emperor to make an "Imperial Decision," an extremely unusual request. Previous meetings simply asked the Emperor to rubber stamp the council's unanimous decision. The Emperor expressed support for those who favored ending the war. That led to the decision to accept the Potsdam Declaration.

At dawn on August 15th, Suzuki's house was burned down by Japanese military personnel who were furious with him for ending the war. He narrowly escaped. At noon, Emperor Showa announced on the radio that Japan would accept the Potsdam Declaration.

"Everlasting peace"

Now 87, Michiko has only recently started speaking publicly about her grandfather's life. She always includes his last words.

"I was sitting to his left, rubbing his hand," she says. "The last thing he said before losing consciousness was 'everlasting peace,' which he said twice."

Michiko also says her grandfather wanted leaders after the war not to lie to the people as the wartime government did. And he wanted Japanese people to make unrelenting efforts to protect peace.

His legacy

Even among historians, opinions are divided over the four months between Suzuki taking office and Japan surrendering.

Some say he should have accepted the Potsdam Declaration earlier, before the atomic bombings and the internment of Japanese soldiers in Siberia.

Others praise Suzuki's careful maneuver to end the war. They say without it, a civil war might have broken out between those for and against ending the war, as happened in Italy.

Or Japan may have endured a grueling land battle, as Germany did.

All we can say is that a withdrawal in such a situation is one of the most difficult decisions a leader can make. In that sense, it is meaningful for people today to look back on the role Suzuki played.

With the world becoming more unstable, Kantaro Suzuki reminds us how difficult it is to bring international conflict to an end once it has spun out of control.