This followed a Japanese court’s landmark ruling last month that the government must pay a total of over 3 million dollars to more than 500 plaintiffs -- family members of former leprosy patients. The court said the past policy of forcibly isolating patients in special facilities violated not just the patients' rights, but those of family members as well.

On that day, I was in front of the court waiting for the ruling. There, I saw Michiko Kocho, whose grandfather was a leprosy patient. She was holding an extraordinary painting. She said she thought it symbolized the pain of families who were torn apart because of the government’s policy and fought for justice for many years.

The story of "Family"

The oil painting was titled "Family" and looked like a self-portrait of a man and a woman holding a baby. It was done by a former leprosy patient who lived most of his life in a separation facility in the southwestern city of Kumamoto.

The painter, Kiminao Okui, was diagnosed with leprosy when he was a teenager. He loved painting and his motifs were often scenes from his home, the tropical island of Amami.

Okui fell in love with another patient and they got married. But under government policy, they weren't allowed to have children. If a couple at such a facility wanted to marry, the man was required to be sterilized. If the woman was pregnant, she had to have an abortion. The exact circumstances for Okui and his wife aren't clear, but they couldn't have children. Okui painted "Family" in his later years, but he never spoke of it. He died at the facility.

The story of Michiko Kocho’s family

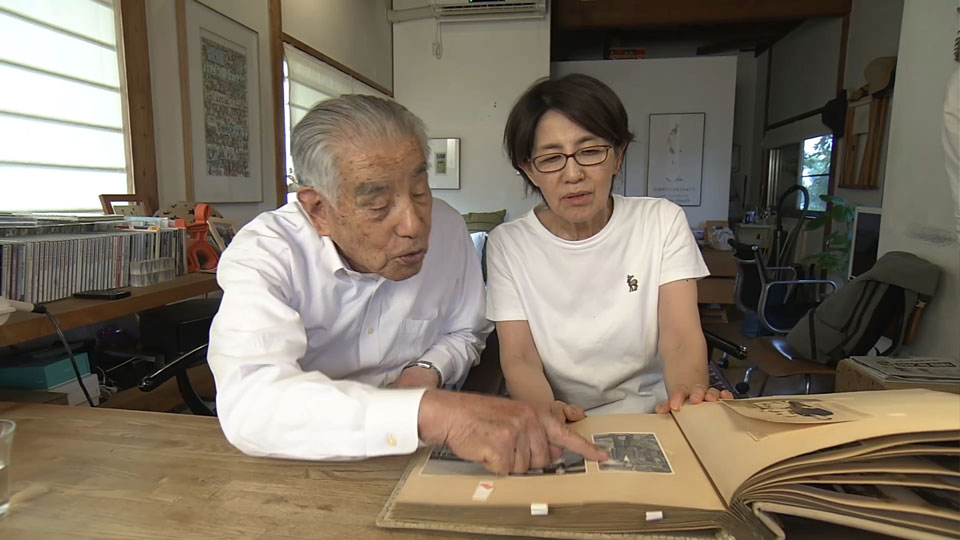

Michiko Kocho’s father, Chikara Hayashi, is the leader of the plaintiffs. He is 94 years old. They both live in Fukuoka. Kocho grew up not knowing anything about her paternal grandfather until the age of 19, when Hayashi published a book in which he mentioned that his father was a leprosy patient.

Hayashi’s father Hirozo was diagnosed with leprosy and taken into an isolation facility when Hayashi was 12 years old. He remembers the shock he felt when his father had to leave. "My father said out loud, 'I'm going, Chikara,' three times. He asked, 'You're not seeing me off?' So finally, I ran toward the door. He was already walking away. I remember it so well. He was limping." The facility was far from home and the rest of the family was afraid of the stigma, so they moved from one place to another, hiding the fact they had a family member who had leprosy.

Hayashi later married and had a daughter, Kocho. But he never took her to see his own father. That's one regret he has.

When Hayashi's father died in 1962, a doll of a small girl was found in his room. It was a present Hayashi had sent. On the back of the glass case of the doll were the words "my granddaughter."

Kocho said, "He probably wanted to hold me, his own granddaughter. Me, his own granddaughter. He must have."

History of the families’ lawsuit

The government's isolation policy ended in 1996 following a court decision, five decades after a cure was found. Compensation for former patients began.

But Hayashi felt the suffering of families needed to be addressed, too. All of them suffered from segregation and social stigma. Hayashi became a leader of plaintiffs and Kocho started to support him in 2015. Around that time, Kocho encountered Okui’s "Family." She knew by then that the government policy hurt had many couples like Okui and his wife, who couldn’t build families. Kocho said, "There were children like this one who were not allowed to be born into this world. We feel that these people are with us, fighting for our rights. We want to remember their feelings too."

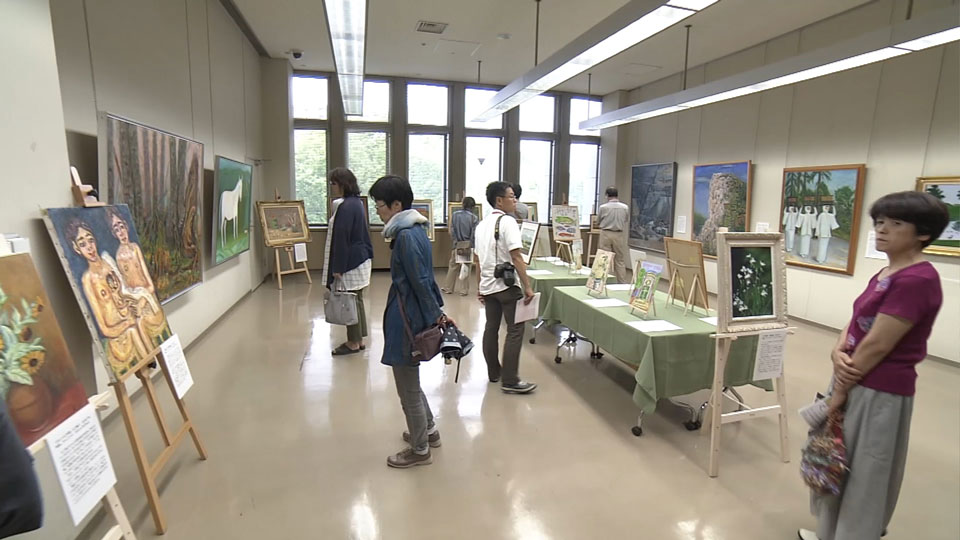

Paintings of former leprosy patients

Right before the ruling, a few dozen paintings were exhibited at a Kumamoto library not far from where Okui lived. All works were by former leprosy patients who lived in the same facility as Okui.

They included familiar sceneries of their hometown, such as mountains, portraits of their family members whom they missed very much, and dream houses that they couldn’t build. Okui’s "Family" was among them.

Event organizer Emi Zoza has been preserving the more than 800 paintings Okui and eight other former patients created at their facility. Most of them have passed away. Zoza believe these paintings tell the stories of their deprived freedom and the desire they had to go back to their homeland until their last breath. She thinks they will educate future generations about the issue.

The family’s struggle continues

Following the Prime Minister’s apology, the plaintiffs held a press conference in which the leader, Hayashi said, "I want to say to my father, 'Dad, we have finally come to this stage.'" He also said that discrimination against the families would not disappear overnight and wanted "the prime minister and government to do everything possible to correct public misperception through education." He says the families are ready to work with the government for that.

The families say the ruling of the court and the government’s apology is only the first step. There will be a long road ahead, they say, to the day when they see no more discrimination.