Kimiko Ota lived in the city of Kasamatsu in central Japan's Gifu Prefecture. In her 80s, she suffered a heart failure and had surgery. From that point on, she was in poor health and was regularly hospitalized. When she was at home, she was almost always in bed.

Her daughter asked her to come live with her, but she declined the offer, saying she would rather stay home, even if it meant being alone. Her daughter thinks she probably wanted to finish her life in a comfortable setting, rather than moving somewhere completely new at such an advanced age.

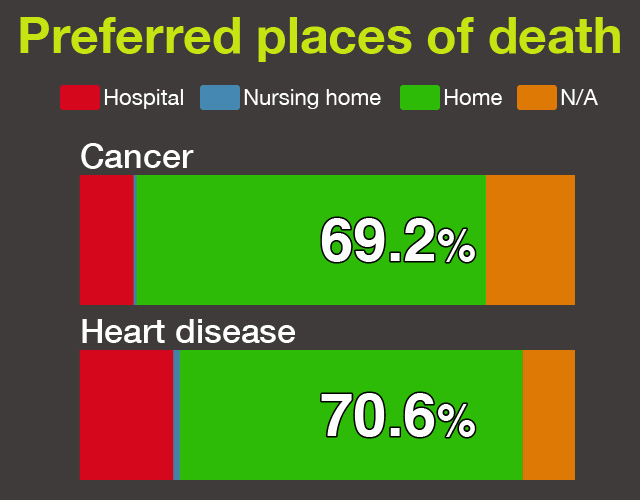

In a survey published by Japan's health ministry this March, 69.2 percent of respondents said they would want to die at home if they had terminal cancer. 70.6 percent said they would want to die at home if they had a serious heart disease.

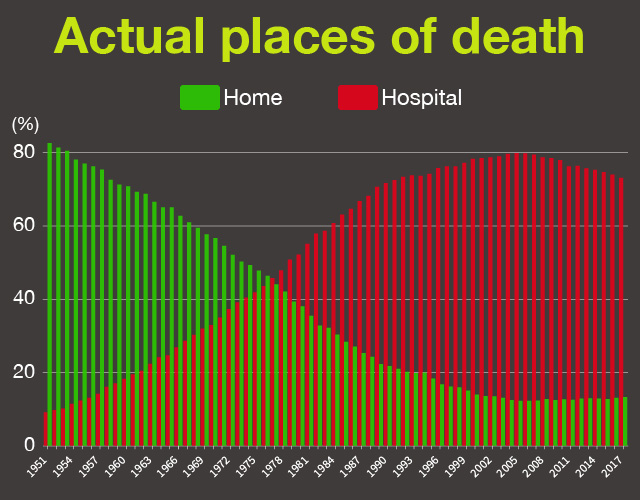

But according to a demographic survey by the Health Ministry, only 13.2 percent of people die at home. This number has been steadily declining over the past 70 years. In the 1950s, 80 percent of people died at home.

Kimiko's wish to die at home was made a reality by a team led by Bunyu Ogasawara, a doctor who has been providing patients in the area with home medical care for 30 years.

The team was made up of not only doctors and nurses, but licensed care managers, home care helpers, and staff from the adult daycare center Kimiko went to.

Kimiko liked to be bathed at the daycare four times a week. The team did their best to allow her to continue this practice, taking precautions like making her bed in a way that prevented bedsores and applying skin lotion. They also helped her with masticatory rehabilitation, so she could eat whatever she wanted.

The personalized care enabled Kimiko to lead a stable life alone at home. Ogasawara says this kind of home care can actually extend a patient's life compared to normal hospital treatment.

About six months after Ogasawara's team began the personalized care program, Kimiko's condition started to deteriorate. Eating became difficult. Her respiratory functions weakened and she was forced to start using an inhaler. Her condition stabilized around Christmas and she was able to eat cake with her grandchildren and great-grandchildren who visited her at home. Five days later, she passed away. Just six hours earlier, she had eaten a cream puff with her daughter.

"Of course I'm sad my mother is dead," the daughter says. "But I was able to help her live the way she wanted until the end. I'm happy I was able to spend time with her and I think she would be happy if she saw this photo."

The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research says 1.34 million people died in Japan in 2018 and the number is projected to rise to 1.6 million by 2030.

Ogasawara says home healthcare will become more important as this number continues to rise.

"Death is viewed as a failure and something to fight against, but quality of death will be more important in the future," he says. "The atmosphere in hospitals can often feel tense, whereas at home people can relax. People can die in peace at home."

Last year, the government revised the guidelines for terminal care and set criteria for home treatment and care for patients with no hope of a recovery.

Ogasawara's team has attended 15 patients who lived alone and died at home during the past year.