Japan's Emperor has no political power and the constitution stipulates that he is "the symbol of the State and the unity of the People.” Among the many roles the new imperial couple will play, it is hoped they also will be cultural ambassadors, helping to preserve old Japan and its traditions.

Weeks before the abdication, Emperor Emeritus Akihito and Empress Emerita Michiko visited important sites in the western region of Kansai, including the tomb of Emperor Jimmu in Nara, who is believed to be Japan's first emperor, ruling from 660 to 585 BC. The Kansai region encompassing Osaka, Nara and Kyoto, is historically where emperors resided for ages. Kyoto was the capital for the longest period -- about 1,000 years -- until Japan’s modernization shifted the capital to Tokyo about 150 years ago.

Emperors and aristocrats not only ruled from Kyoto, they were also deeply associated with rituals and cultural activities involving poetry, flower arrangement and music. After the Imperial family left, Kyoto continued to be the cultural and spiritual heart of Japan. This is why so many festivals and special events are being held in the ancient capital to celebrate the arrival of a new imperial era. Temples are displaying Buddha statues and other relics normally hidden from public view.

Daikakuji temple in northwestern Kyoto was once a villa of Emperor Saga, who lived during the 8th to 9th century. It is said that he loved flowers and created a school of flower arrangement. The festival at the temple drew hundreds of tourists, including disciples of the school. “With the new emperor, we would like to continue preserving Japan’s culture and pass it on to future generations," said Shunyu Ise, head of administration at Daikakuji.

As Japan rushed to modernize in the late 1800s, it was feared that centuries-old traditions would be lost. Samurai warriors had their long hair cut short and abandoned their swords. People were encouraged to start wearing western-style clothes. The Imperial family was moved to Tokyo.

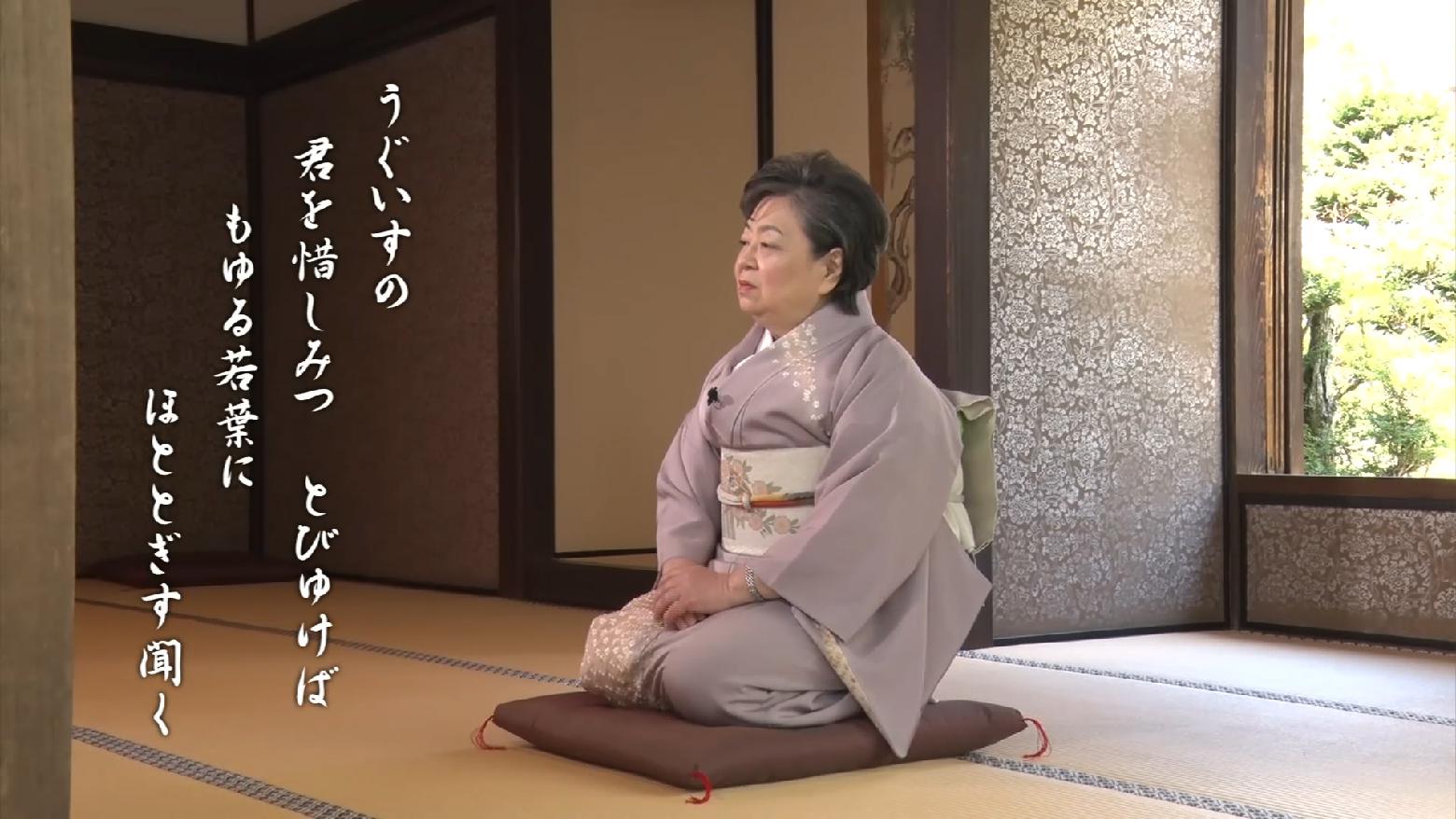

“Many aristocratic families who accompanied them were the first to abandon kimonos and wear western dresses, and they learned how to dance the waltz,” said Kimiko Reizei in Kyoto. Reizei’s ancestors were aristocrats who worked in the Imperial court for generations, but they chose not to move to Tokyo. Her family home is the only traditional Kuge (noble) style building that remains intact. The Reizeis were a house of poets. Kimiko also writes poetry called Tanka, consisting of 31 syllables, and teaches students from across the country.

She still uses the old lunar calendar at home and conducts annual rituals and seasonal festivals. On the day I visited, she had a traditional set of dolls on display expressing a wish for the happiness of female children. During the last 150 years, Japan has been heavily influenced by western culture, says Kimiko, but she believes that in the age of globalization, it is especially important to know your cultural roots.

“Historically, the core of Japanese culture was nurtured by the Imperial court," she said. "I hope the new Emperor and Empress continue to be at the center of our traditional culture, and through them, the world will see a new Japan.”