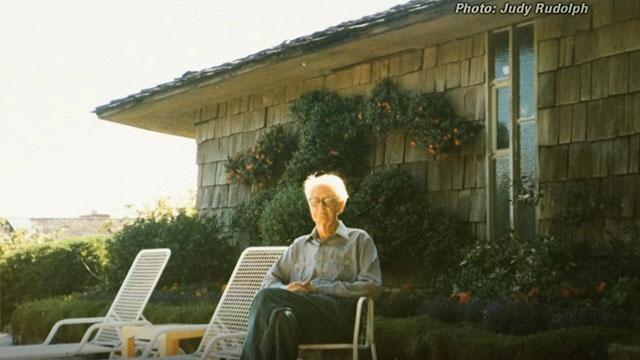

The lifelong pacifist is remembered for his work in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where he put together teams of multinational volunteers to help build houses after the 1945 atomic bombings. He dedicated his long life to working for peace until his death at 105 in 2001.

Before the documentary screening, I visited a small Seattle peace park that Schmoe established when he was 94. It features a statue of Hiroshima victim Sadako Sasaki, who folded origami paper cranes to represent her hope of recovering from leukemia.

She never did recover and was just 12 years old when she died, but she inspired Schmoe to remember her in his park, along with his never-ending quest for peace.

In the years since, the memorial has become a place for children to think about peace. On the day I was there, kids from a Seattle elementary school were visiting to lay paper cranes on the statue. One fifth-grader said Schmoe made him realize that building peace can begin with a simple thing, such as being a kind person and inspiring kindness in others.

January 13th was a sunny Sunday -- rare for Seattle in winter. Despite the good weather, nearly 450 people came to make the screening at the University of Washington a full house. Host NHK set it up in cooperation with the university where Floyd Schmoe once studied and taught.

"Houses for Peace: Exploring the Legacy of Floyd Schmoe" includes new material discovered in the university's special collections.

Seattle once was home to one of the largest Japanese-American communities in north America. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, the US government considered Japanese-Americans "enemy aliens" and forcibly relocated about 120,000 people from the west coast to inland internment camps.

Most Americans said nothing, but Schmoe thought it was wrong and spoke out. When his protests were ignored, he quit his job at the university and dedicated himself to helping Japanese-Americans.

He made numerous trips to the internment camps to do what he could to help those held there. He searched for colleges in the eastern United States that would accept Japanese-Americans so they could continue their studies. Aki Kurose was one of many who were supported and inspired by Schmoe. She went on to become one of the United States' greatest educators.

Kurose was 17 when she was moved from Seattle to camp Minidoka in Idaho with her family. Schmoe's efforts enabled her to leave the camp and study at a university in Kansas. The experience gave her a strong appreciation for social justice and peace.

After the war, she returned to Seattle and became an activist fighting against discrimination and for peace. She worked with Schmoe, who remained a mentor throughout her life.

She also started teaching in 1970s and infused her classrooms with appreciation and respect for different ethnicities and cultures. She received many awards, including the Presidential Award for Excellence in Education and the United Nations Human Rights Award, and remained active until her death in 1998.

The following year, the Seattle School Board named Aki Kurose Middle School in her honor.

I visited Kurose's sister and son prior to the screening. Suma Yagi is two years younger than Kurose. Unlike her outspoken sister, Suma kept quiet about her internment, as did many other second-generation Japanese-Americans.

The only way she could express her inner words was through the poetry she started writing after she retired.

It took so long as her experiences were still too painful to talk about or even remember. But, she says, she felt the need to share them so that sad chapter of history wouldn't be repeated. She also wanted people to know that there was someone like Schmoe who really cared about them, despite the strong hostility and discrimination against Japanese-Americans. Kurose's son Paul says his mother always shared the importance of standing with others in the face of injustice -- precisely what Schmoe did for their community. He says that's why his mother followed in his footsteps.

Both Suma and Paul attended the screening along with many others who were interned. They told me of their hope that their government should never repeat the mistake of ostracizing people because of their ethnicity or religion.

After the screening, I met Kathryn Cunningham, a fourth-generation Japanese-American. She says the theme of the documentary felt timeless. She says Schmoe was never swayed by other people and that's something we can all learn from. She says if we have that strength of heart we can overcome anything, as peace and the desire to achieve it are timeless. As Schmoe proved, we can rise above whatever is happening around us to work for what we believe is right.

Paul Kurose says his mother would have been overjoyed to be there and see people taking in the message about the difference that just one person can make in working for peace.

Suma Yagi says she wants American society to grow to accept people of different colors and to support each other as race does not matter. She says she's sure that's what her sister would have wanted too.

In 2019, the world seems to be going through an era of division that's the opposite of what Schmoe and Kurose worked toward. But, as the history of the Japanese-Americans who faced discrimination before shows, there remains hope that the power of individuals standing together against injustice can be more powerful than the forces that try to cast out racial and religious minorities.