Utsumi Naoko's life may have been saved by the spread of her son's Twitter post saying, "My mother and many children are stranded on the third floor of a community center in Kesennuma City, Miyagi Prefecture. If a helicopter rescue is possible, please at least help the children."

Utsumi was the director of a child welfare facility next to the community center. After hearing that a major tsunami warning had been issued for Kesennumma following the massive quake, she immediately evacuated to the community center along with 400 other people.

She and the children ran up to the roof to await rescue. The tsunami reached the ceiling of the second floor.

Seeing fires breaking out in the surrounding area and snow starting to fall, a fearful Utsumi e-mailed her family to explain her perilous situation.

Utsumi's e-mail reached her son in the UK, who then posted on Twitter.

His tweet spread and eventually reached the office of the Tokyo deputy governor, which directed the Tokyo Fire Department to rescue all the evacuees by the following morning.

Recalling the rescue, Utsumi said, "Tsunami waves kept coming and I thought that was it. When the firefighter said, 'I came to rescue you upon your son's request,' I didn't understand but I was happy we'd be saved."

She later learned how the rescue had come about and said "it was a miracle" that she was saved by many people thinking they had to pass the tweet on to others."

But she added the situation would be different now with the advent of malicious social media posts.

Fulfilling a critical social responsibility

Ishimori Daiki, who hails from Miyagi Prefecture's Ishinomaki City, has been issuing disaster information on social media via a company he set up in 2010 when he was 19.

Following the loss of his aunt in the 2011 tsunami, he redoubled his efforts.

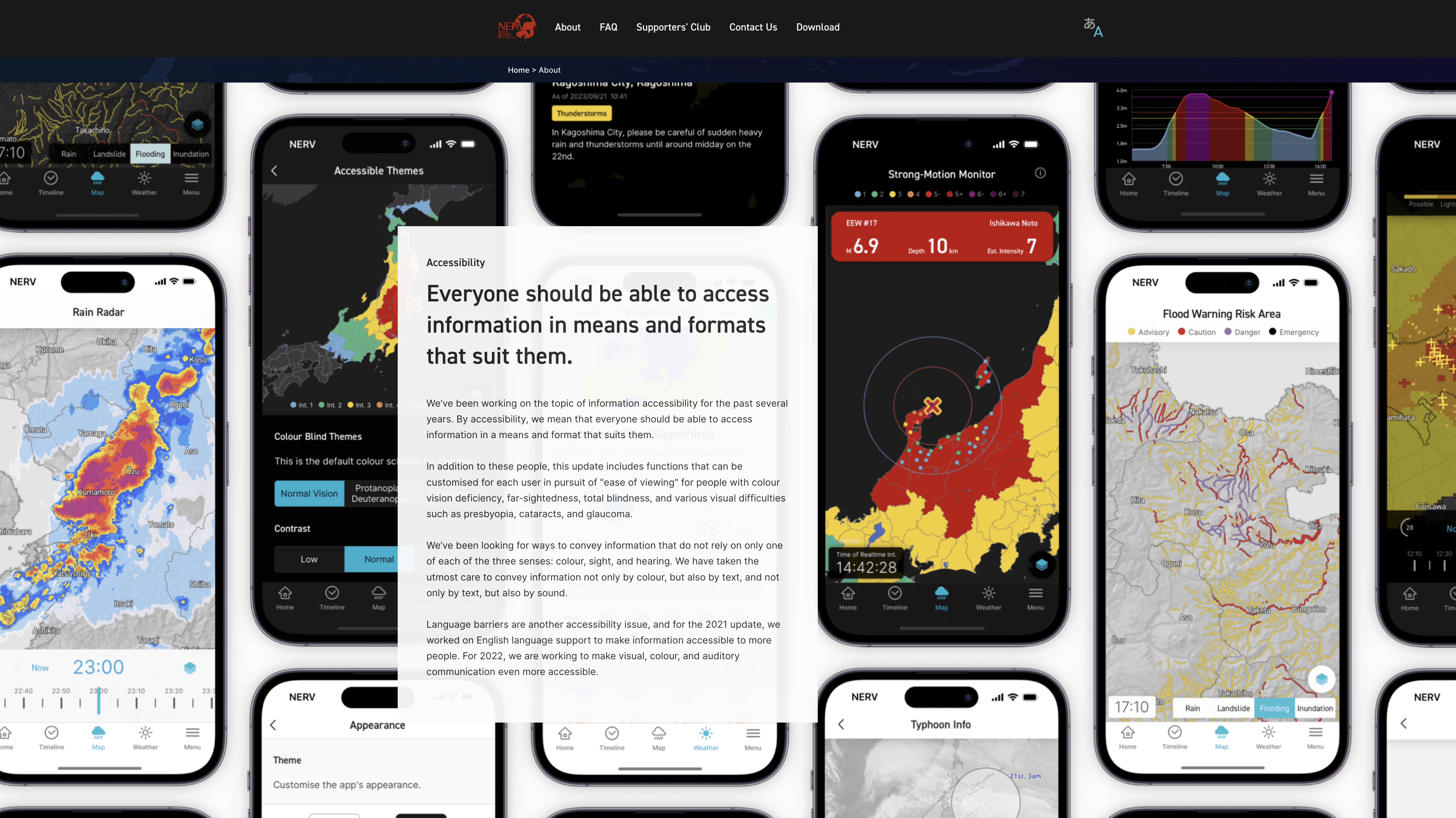

His timely posts provide information about earthquake early warnings, heavy rains and volcanic eruptions that are based on data from organizations such as the Japan Meteorological Agency. They're extremely popular on his own app as well as on X, where he has 2.3 million followers.

During the Noto Peninsula quake disaster, NERV reached the limit of X's application programming interface for daily messages.

Ishimori posted on X telling his followers that because of the API limit, he could no longer post on X and asked people to download his app.

X removed the restriction a few hours later after it confirmed his account was playing a key public role. Nonetheless, he decided to reduce his reliance on X.

His app has been downloaded more than 4.5 million times.

Ishimori says, "Once someone dies, they don't come back no matter how hard you try." He's committed to obtaining information quickly as possible and sending it to his followers, saying it's the responsibility of those alive today to leave behind mechanisms that provide safe information.

X video hijacked to spread fake information

The January 1 earthquake damaged many buildings in Noto Town's Matsunami area. Kinshichi Seiko's sake brewery collapsed.

Kinshichi, who was at home next to the brewery when the quake struck, took a video of the surroundings and posted it on X to convey the damage in Noto Town.

The video, however, was hijacked and used to request help at an address in Suzu City. The post, which said, "Trapped and can't' escape," went viral. Some reposts had 550,000 views.

Most reposts were made from overseas. Experts have speculated they were done to make money based on views.

Kinshichi recalls, "Since the area we live is far from the center of the town, I thought no one was going to help us and I decided to make a post."

While she thinks most people who reposted the false information had good intentions, she wished they had taken time to check the information source.

Out of 1,091 posts collected by national research organizations concerning rescue requests made in the 24 hours after the first Noto quake, 104 of them — about 10 percent — turned out to be fake using non-existent addresses.

Expert: Use multiple media outlets to improve reliability

The number of people using X in Japan has more than tripled over the past decade. It's one of the most popular social media platforms.

Tohoku University's Associate Professor Sato Shosuke notes there are now more posts showing what's happening in disaster areas and believes social media firms must devise ways to prevent the spread of false information. He says laws are also needed to give teeth to such efforts.

Sato says when disasters took place in the past, people in affected areas relied on information from TV and radio. And they shared information through their LINE or Facebook communities.

He says people should seek out multiple media combinations — including television and radio — to ascertain the reliability of disaster-related information.