Komine Shurina is a teacher in Minamisoma City, Fukushima Prefecture. She is confronting a fundamental question, "How can I pass on the memories of the disaster, as someone who has not truly experienced suffering myself after the earthquake and the nuclear plant accident?"

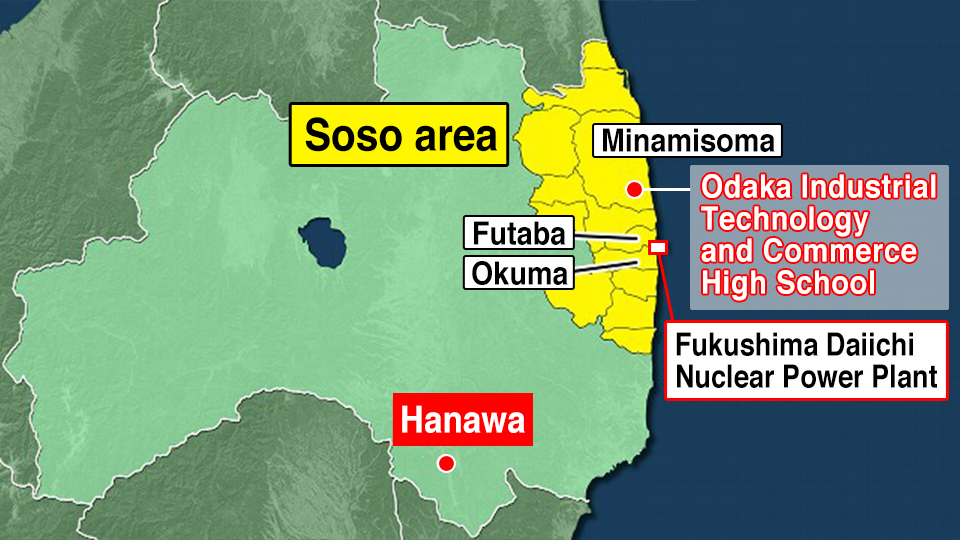

Komine got a post as a geography and history teacher at the Fukushima Prefectural ODAKA Industrial Technology and Commerce High School five year ago. Most of the approximately 360 students are from the Soso area, where many people were killed in the tsunami. Following the nuclear power plant accident, the area was issued evacuation orders.

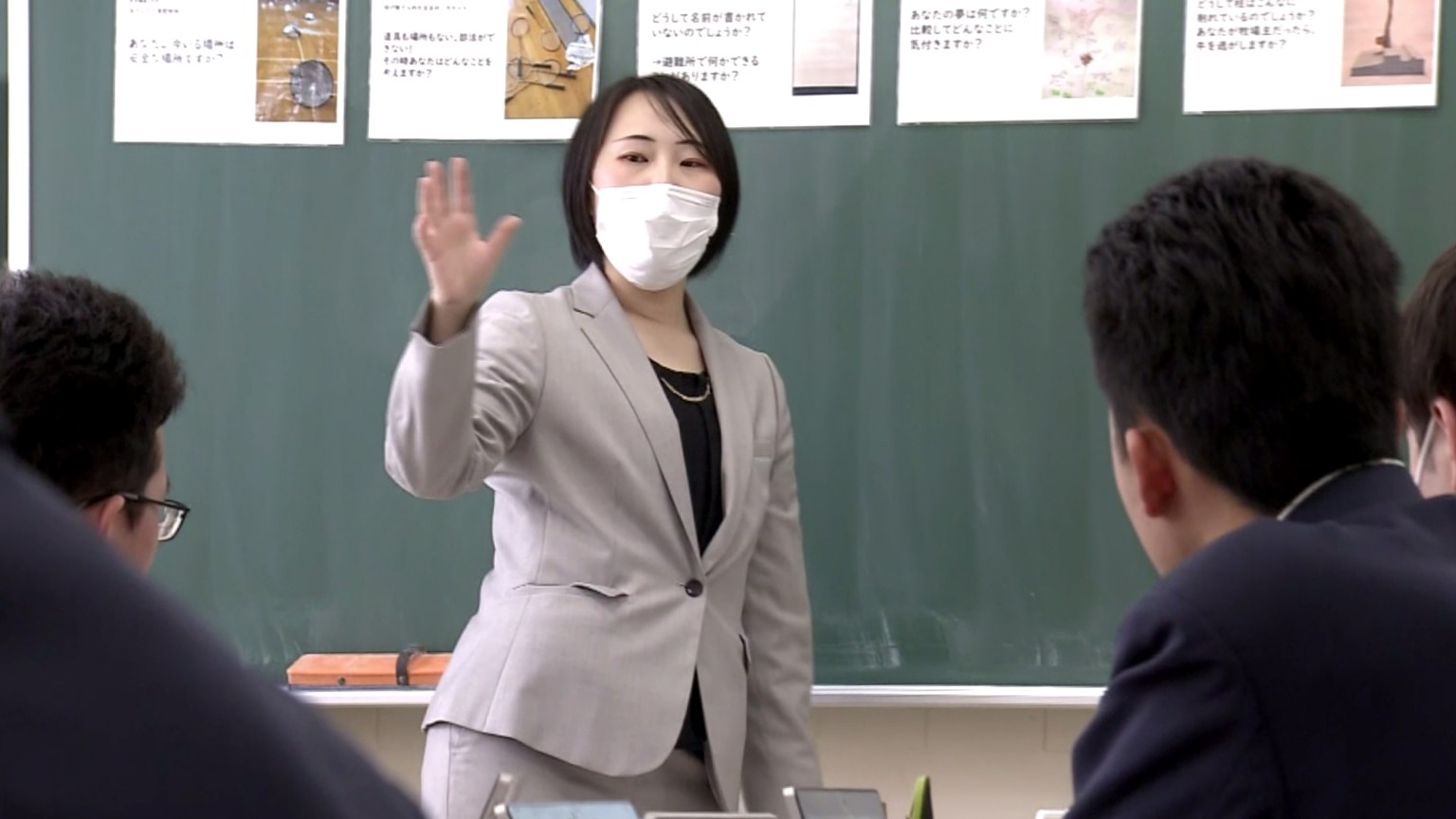

Students take the lead in class

In early February, Komine held her first disaster prevention class to a class of second-year students. But instead of a teacher-led lesson, the class content was developed by the students themselves.

The students form groups and use materials that tell the story of the disaster. For example, they show a replica of a pillar gnawed by cows suffering from hunger when they were stranded in a cowshed in the city after the nuclear accident.

The students talk about how they feel, as they touch the pillar.

"The cows had nothing to eat besides this. They had no other choice but to chew on the pillar. I feel so bad, so sorry, why didn't the farmers let them go?" one student asks.

Then another says, "Because they would become feral animals, they would be wild."

They also look back on the time of the earthquake together.

Komine spoke to NHK about the reason why she adopted the style of "thinking together" instead of "teaching."

"Because they were born and raised in disaster-stricken areas, I want them to be the bearers of their own memories. I want them to pass on their personal stories to the next generation and people in the communities and not just repeat what they hear from someone else. I want them to put their own thoughts into words," says Komine.

Born in Fukushima, but living at a distance

Komine was born in 1992 to a family who run a grocery store in Hanawa Town, located in the southern part of Fukushima Prefecture. Shortly after graduating from high school, the Great East Japan Earthquake struck. With a seismic intensity of lower 5 on the Japanese earthquake scale of zero to seven, the house and store belonging to Komine's parents were damaged.

The following month, Komine left Fukushima to attend university in a nearby prefecture.

She took a teaching job at a high school after graduating from university but her new position at ODAKA gave her many concerns.

"Compared to my students, I feel my experience of the earthquake is small. I am not from this area, nor did I see the tsunami's damage with my own eyes," Komine said.

She continued: "Is there anything I can teach about the earthquake? What if my words cause the students to have flashbacks of their painful experiences?"

Teacher avoids using the words 'earthquake' and 'nuclear power plant'

A number of students lost their family members in the tsunami, and were forced to live in evacuation centers for a long period. Being careful not to hurt their feelings, Komine tried to avoid mentioning the words "earthquake" and "nuclear power plant." And she was not the only one.

But, at the same time, she and other teachers were concerned that memories of the earthquake were weakening among students who were in kindergardens at the time of the disaster.

Komine told herself that, as a history teacher, she has to tell the story. But she was struggling.

A turning point came when she heard the words a student spoke during a geography class.

"I was showing an aerial photo of an area that happened to have been damaged in the tsunami, and one of the students suddenly said, 'My house stood there.' When I heard that, I realized I had become too sensitive," said Komine. She reminded herself that she doesn't have to shy away from talking about the disaster and she can talk about it from the perspective of someone who did not experience the harshness of the disaster firsthand.

And this is what made Komine hold her first class on disaster prevention in February — the class we introduced earlier in this article.

Thinking about the earthquake's legacy

With the cooperation of Fukushima Prefectural Museum, the museum's collection of objects related to the earthquake was brought into the classroom.

Among them is a light that fell off the ceiling of the gymnasium at Tomioka High School, and notes describing the tasks assigned to those who evacuated to Namie Junior High School after the nuclear accident. These chores included serving meals and cleaning the bathrooms.

Reacting to the objects, students expressed such thoughts as, "I would panic if a light this size fell," and, "What we can do at the evacuation center is take care of the elderly and carry relief supplies."

Komine urged students to talk about their memories of the earthquake.

One noted that, "In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, not only cows but also we humans were not able to get food. So I want many people to think about how they would secure food and water in a disaster."

Another said, "I want to tell everyone that everyday life will not necessarily return tomorrow and that you won't be able to do the everyday things you normally would."

Komine said, "I feel that I have finally been able to face the earthquake and the nuclear accident head-on, and it was a big advance for me to think about the disaster with the students."

In addition, she said she would expand the initiative, such as providing opportunities for current students to become storytellers and give disaster prevention classes to junior students and people in the other communities.