I didn't notice, but I started to slip. Sometimes I raised my voice at the nurses. I blamed myself, and even felt sorry for my patients.

'I am incompetent'

Unfortunately for my patients, I was not capable. I had no idea what treatment to pursue. I felt they may not even recover, because I was the one responsible for their care. My seniors were excellent. I wished they had been the doctors. I worked as hard as I could. But even if I cut down on sleep, I couldn't keep up.

'I am always supposed to get full marks'

My strength has always been to work hard and never slack off. From elementary school, I notched perfect attendance. 100 percent was my normal exam mark.

I was hard on myself through medical school. After graduation, the two years of training were sometimes tough, but I learned from different departments and relaxed by going drinking with my colleagues.

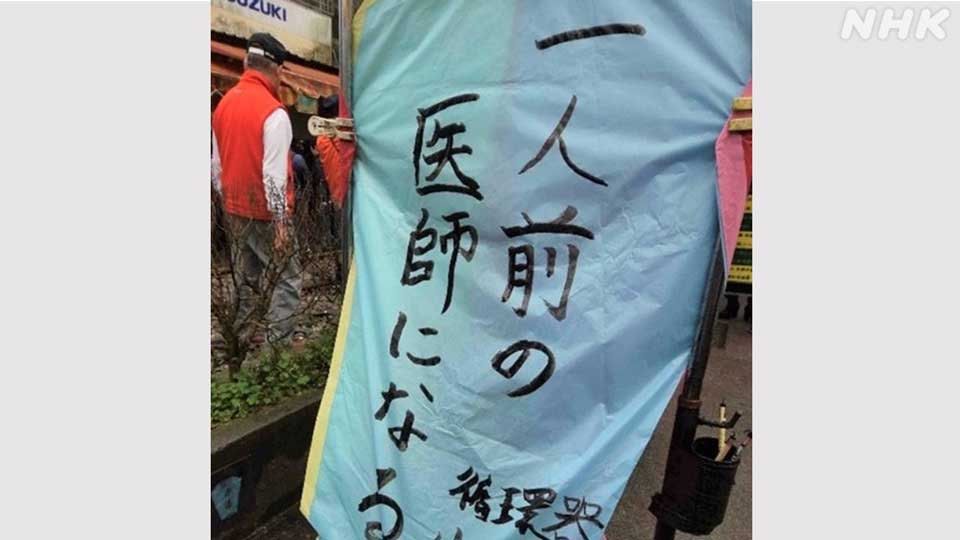

I was fascinated by the senior physicians, and in my third year of training began aiming for a career in cardiology, specializing in heart and blood vessel diseases. At a party, I vowed to my colleagues: "I will become a full-fledged doctor."

In my third year, I shifted to a hospital with a high reputation and excellent staff. I was prepared for a challenge, but I told myself I was still learning and must do whatever it takes, whether it meant working on holidays or cutting back on sleep.

There was a lot to absorb, with more practical procedures than book learning, and I became an attending physician for the first time.

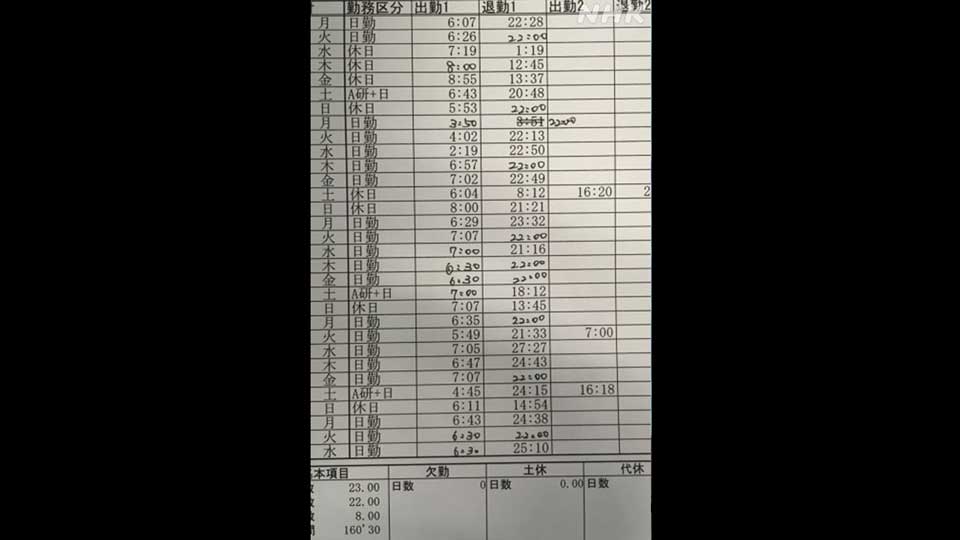

I went around the wards examining patients from 7:00 a.m. and later trained in specialized treatments. Catheterization, in which small inflatable tubes are inserted into blood vessels, is one of the basics. But already the work was getting too much for me. I recorded those days in my diary, which I had kept since high school:

April 3

I had a hard time. I couldn't even get the balloon in. I will reflect on this and move on to the next task.

April 6

I never finished writing up my reports on the patients. If I don't do the work, my future will be tough.

April 7

I'll make a flowchart and add a template. I have to cut down the time I spend on these things.

In the afternoon I saw emergency patients and in the evening I joined a review at a staff conference. I think I gulped down food before 7:00 p.m. then continued to see patients in the wards until around 10:00 p.m. I would lie down for a while on a hard bed in the examination room and wake up at 2:00 or 3:00 a.m. While I was sorting through the stacks of medical records, dawn would come again.

"I'm not good enough," I told myself repeatedly.

I stopped going home because I didn't want to waste even 30 minutes commuting.

May 10

I was shocked at logging 200 hours of overtime in April. That's the level you die from overwork.

What they call karoshi or death from overwork is when someone exceeded 80 hours per month. I had logged two-and-a-half times that. But I did not take a day off even in May.

Gradually, anomalies appeared.

May 11

There are so many things I don't understand, it's getting harder and harder to be nice to people.

May 12

I'm reaching the limit.

I didn't notice, but I had started to slip. Sometimes I raised my voice at the nurses. I blamed myself, and even felt sorry for my patients. I was embarrassed by my lack of skills.

One day during the Golden Week extended holiday I managed to get off work early and went to a movie with friends. It was a series I look forward to every year.

But it was a weird day. My friends laughed, but I couldn't find the movie funny at all. Not because of the content, but because I could no longer relate to having fun.

May 18

I want to quit my job.

Then, in late May, I could no longer keep a diary.

A world in black and white

At this point, I think I was still lucky. In June, I happened to be alone with my boss. I blurted out, "I'm struggling." My boss responded immediately. Later that day I visited a mental health clinic, and then took a leave of absence. But somehow this left me in even more pain.

For a few days I did little but sleep. After a while I began to feel frustrated by doing nothing. I had no hobbies, energy, or vision for the future. I just repeated the same days. My world felt monochrome. In the end, I resigned from the hospital and gave up on the department I had longed to work for.

Burnout syndrome

A loss of motivation to work is a recognized symptom of burnout. In fact, there are many doctors who suffer from it. Experts say physicians who experience such symptoms vary according to survey methods and other factors, but the minimum reported in domestic results is about 20 percent, and the highest about 50 percent. The figure for doctors is believed to be higher than for other professions.

Dr. Shikino Kiyoshi, an associate professor at Chiba University's Graduate School of Medicine, has been studying the condition. "It's clear that overwork tends to cause burnout," he says. "Doctors work long hours, especially younger doctors, and changes in the environment, such as training, can also be a factor."

Unable to show weakness

Shikino says burnout among physicians is rarely discussed. He says the reason is the enduring belief that the condition depends personally on each physician.

"And there is a stigma around burnout," he says. "This means there's shame in talking about it. Doctors think that if they talk about it, they will seem weak and it will undermine their credibility. But doctors are not perfect. They are human."

Shikino says one effect of the coronavirus pandemic was to bring the risk of burnout faced by medical workers to the public's attention. The authorities are finally acting. Labor reforms will begin in the next fiscal year. To reduce the burden on physicians, overtime will legally be limited to a maximum of 1,860 hours, equivalent to 155 hours per month, starting April 2024.

But Shikino argues that short-term reductions in hours will not in themselves prevent burnout. What's also needed, he says, is to "substantially reduce the burden on individual physicians by letting them work in teams, and to share their duties with other professions. We must also create systems to collect data on signs of burnout at the organizational level, and to establish environments in which each physician can work with a sense of fulfillment and enthusiasm."

Finding his own pace

Now 33, Iino told us about his new life. After retiring from the hospital, he changed his specialty and became a general practitioner. He now works at a clinic in Osaka, providing home visits to local patients.

As head of the home-visit team, Iino still encounters problems, but he knows how to respond. He falls back on the coaching interviews he has undergone. He can now display his weaknesses. By putting his feelings and values into words, he can see himself with a detached point of view.

He looks after his health and has joined a local running team, scheduling his evening appointments to ensure he finishes work in time. His new goal is to run a marathon.

"We tend to run after ideals, but I think it is important to pause," he says. "Not to stop completely, but while continuing to move forward, even only a little, to keep an eye on our pace."

"I think the view you see while running, the view you see while driving a car, and the view you see when you stop are different, so I want to make my life one where I can enjoy the pace of different ways of moving.

"Today was another good day. Now all I need is a tasty meal and I will be satisfied."