Honjo said huge investments are being made in sectors such as automobiles that are key pillars of Japan's industry. But he said it seems that life science is being treated somewhat lightly. He pointed out that in the US and European nations, half of science-related policy spending goes to life science, while the proportion in Japan is only around 30 percent. Honjo said this is wrong.

Many other Japanese Nobel laureates have sounded similar warnings in recent years.

Shinya Yamanaka, who won the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, said he worries there's a slight tendency that the importance of basic research is being underestimated.

Yoshinori Ohsumi, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in the same category in 2016, said Japan doesn't deserve a good reputation just because it has produced many Nobel Prize winners. He said he harbors a deep sense of crisis that the fields of science could be hollowed out in Japan.

Posts sharing such concerns can be found on social networking sites. One of them says a number of prominent researchers, including Nobel laureates, have been stressing the importance of basic research, but their calls are being ignored.

Another says Japanese winning Nobel Prizes in science-related fields bears great significance, but there's no guarantee this will continue. It warns that as basic research is treated lightly, there may not be enough instructors after the current generation of laureates retires. It says the scientific fields could be hollowed out someday.

A different posting says that if Japan fails to invest more in basic research and instead focuses on quickly generating profit, it will not produce any more Nobel laureates. The message warns Japan should not rest on its laurels.

Data indicate Japan's basic research faces crisis

1) Japan's budget for scientific advancement is one-fifth of China’s

Japan's budget for science and technology this year hit an all-time high of 3.8 trillion yen, or about US$33.8 billion. But from a global perspective, China's presence has been increasing among major nations, and it has overtaken the US to secure top place. In 2016, China's budget stood at around 22.4 trillion yen, or roughly US$199 billion. That's more than 5 times the funds Japan allocated.

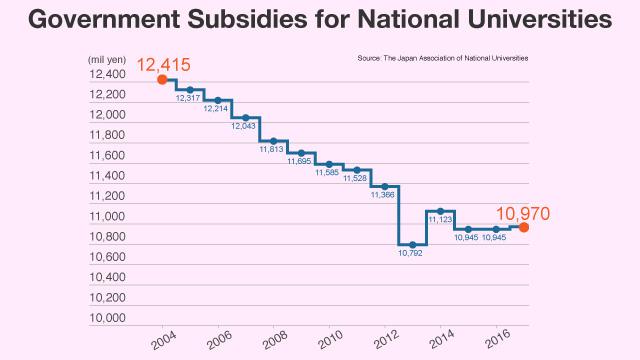

2) Subsidies for national universities have been cut

Subsidies for operational fees that state-run universities can use for purposes such as basic research have been falling. In 2017, they fell by more than 140 billion yen, or around US$1.2 billion, compared with fiscal 2004.

3) The number of young researchers at national universities has dropped

The percentage of full-time faculty members under the age of 35 at Japan’s national universities was 17.5% in 1998. That dropped to 9.5% by 2016. As a result, the average age of full-time faculty is rising.

4) Japan's ranking in the number of citations of research papers has fallen

Between 2004 and 2006, Japan ranked 4th among leading science nations for citations of research papers. Its ranking dropped to 9th for the period between 2014 and 2016.

5) The number of people obtaining doctor’s degrees has dropped

Japan was the only major nation where the number of people obtaining master's and doctor's degrees was lower in 2014 than in 2008.

British science journal Nature ran a feature on Japan’s scientific research last year. It said, “Across Japan, early-career researchers face an uncertain future.” The article also pointed out that Japanese scientific research is at a turning point and that the country may lose its status as one of the world's top providers of research unless it produces results in the next decade.

Nobel laureates contribute

Hidetoshi Koshiba, who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2002, donated his prize money to set up a foundation the following year to promote basic science research. Yoshinori Ohsumi, winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2016, set up a foundation last year and used his prize money to assist young researchers and support creative basic research.

Tasuku Honjo, who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine this year, is planning to donate his prize money to his university to set up a new fund to help young researchers.

Response of politicians

Former Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi stresses that budgets have stopped decreasing.

"Basic figures like basic management budgets for national universities have stopped decreasing, so as a total sum, I think they hit bottom a couple of years ago and are gradually starting to increase, although the increase is not so great. But that is one message I would like to send. We are now trying to increase the basic fee for national universities. And those scientific research fee funds also hit bottom last year or a year before. So this is another sign that the decrease has ended.”

He adds, "We study what’s happening in European countries like Britain, Germany and France, and the EU budget as a whole. They are carrying out good programs despite limited budgets. It’s important to consider what the United States and China are doing, but we can also learn a lot from European countries.”

Hayashi also says the government encourages younger scientists who do research in an international environment.

"Younger researchers have many options for their academic carriers like study and research experiences abroad, during which they can broaden their network within international communities, which can result in joint thesis writing with the foreign academia.”

He has tried to address the declining number of people earning doctor’s degrees in Japan by working with the Japan Business Federation, or Keidanren.

"The questionnaire shows those people who would like to get a PhD, but actually don’t, need more economic assistance. People also they answered that after getting a PhD, they need a job suitable for PhD holders. So when I was in the ministry, we started a communication channel between the education ministry and Keidanren, so that we would know what type of PhD holders they actually need. This is because in the past, companies tried to hire those with PhDs, but mismatches happened. So now, the utilization of some platform between companies and universities should give an understanding of what type of skills, what type of PhD holders the company needs. And then that would have to be reflected in the teaching curriculum in the university side for the PhD. So this matching will be very helpful.”

He insists Japan will be able to keep its position in the world. "If you look at the size of the budget of the United States and China, it’s huge. We should look at their balance sheet -- how many years they have been doing research. China's was very small almost 10 years ago. So theirs has grown very rapidly. Realistically, it’s very difficult to match the size of the budget of China and the United States this year. But like British, Germany and France, that size of a budget... we can utilize huge assets that we have for technology and research and basic stock and intellectual activities. We still have very strong areas such as materials and others. So that’s why I think, you know, keeping at the same level is important to have a higher productivity of thesis writing, compared to European countries, so that we can still stay at the forefront in many areas of science and technology."

Both Japanese authorities and scientists are concerned, but there's hope their efforts will help produce results in the near future.