Minami Daito documents found

Recently obtained documents regarding the island of Minami Daito give a detailed account of the closing phases of the war. About 1,300 people currently live on the island. In 1945, 7,000 soldiers were stationed there and on other nearby islands to protect a strategic airfield.

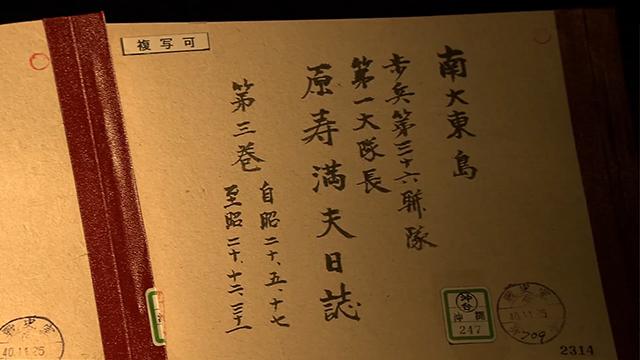

The documents consist of more than 300 pages. They belonged to the military commander defending Minami Daito. They were donated by his daughter in April to the Yasukuni Shrine Archives in Tokyo.

A map shows the positions of cannons and machine guns at 130 locations around the island, and there are sketches giving a 3-dimensional view of the firing field at the different emplacements.

“Most records of actual battlefields tend to disappear," said Kazumi Kuzuhara at the Yasukuni Shrine Archives. "This detailed battle plan is an extremely valuable exception.”

On-site discoveries

We headed to Minami-daito in July, armed with the maps and other records. We put together a team of researchers and local guides to explore the island, including a military historian. The documents pointed to a site on the island's west coast, hidden in the cliffs overlooking the sea.

One of our researchers found a hole at that site that looked like a gun emplacement. The view looked identical to a sketch of the landscape in the documents.

Local authorities already knew about some of the other emplacements, but this was the first time they had detailed records of them.

Another site was barely visible from the beach except for a rectangular opening in the side of a cliff. The documents say this chamber housed a 47-millimeter anti-tank gun.

Japanese soldiers started digging to create the emplacements in 1944. They used chisels and detonators from unexploded US ordnance.

"We believe a single platoon of 30 to 40 soldiers built these defensive positions in somewhere between six months to a year. It required a huge amount of labor," said Tatsushi Saito, Lt. Col., National Institute for Defense Studies.

We managed to track down one of the few survivors of the regiment stationed on the islands. Now in his hometown in Fukui Prefecture, he remembered how the lack of supplies made it difficult to build the positions. "We worked from dawn to dusk, chiseling, making holes for explosives, and then blasting them open," said Hiroteru Ueda, 99, former captain in the 36th infantry. "We had to dig our own holes. That was our job.”

We explored another strategic site on the island, hidden in a cave deep inside a grove. It was the headquarters of the regiment. The cave was large enough to accommodate hundreds of soldiers and the supplies needed to survive for months underground. The map shows the location of a kitchen not far from the entrance. Scattered here and there are signs of everyday life inside the cave as the soldiers prepared for battle.

We found artifacts from that time 73 years ago, including a name written on the ceiling, and an old Japanese dry-cell battery that may have been used in a radio. The underground headquarters is more than 300 meters long.

The diary of an officer on the island conveys his frustration as he monitors events in Okinawa. "The enemy has started landing on the main island of Okinawa. I'm disappointed they aren't coming to Minami-Daito, but we can’t let our guard down for even a second," he writes on April 1, 1945. "The battle of Okinawa is in its final stages. We’re up next. We'll fight bravely," he writes on June 19, 1945.

Two months later, Japanese forces would stop fighting. The war ended without a ground battle on Minami-Daito.

Our team found a burned-out oil drum near the cave headquarters. "It’s possible the soldiers used it to burn important documents in the final stage of the war," said Saito.

On August 31st, the soldiers did one last thing to defend their honor. They burned their regimental flag, so it wouldn't fall into enemy hands. The officers gathered at the time to discuss a difficult choice -- disband the regiment, or commit ritual suicide. The records show that after 30 minutes, Commander Gonichi Tamura chose life and ordered his men to return home.

As to why Tamura decided to preserve these documents, one theory is that he wanted the regiment to be remembered. "I don’t know the sequence of events, but from today's perspective, they are very important documents," said Saito.

Lessons in the remains of war

During our survey of the island, local residents introduced us to the person looking after the stone monument at the site where the 36th infantry regiment's flag was burned. The small statue is in the jungle and largely forgotten, except for this one islander who visits regularly.

"As long as I live, I'll come here at least twice a year to thank them," said Kenyu Shinjo. "I can't begin to imagine how it felt for all these men to burn their flag, to witness the end of the war, and to discover that they would be able to return home alive and well," he said.

Minami Daito never bore the brunt of a full-scale military assault, but traces of the battle they never fought stand as a reminder of the futility of war.

The island is strewn with war-time remains that have yet to be discovered. Our team found 5 sites during our five-day survey, including anti-tank and machine gun emplacements, a monitoring post, and the regimental headquarters in the cave.

The records show nearly 130 strongholds were built. Local knowledge of events and further investigation could unearth more. Minami Daito Village officials say they want to do more to preserve these remains.

This exploration has made me keenly aware of the meaninglessness of the labor mobilized on the island during the war. Most of the soldiers dispatched there were formerly carpenters, farmers or school teachers. They never had to repel an invasion, but air strikes, enemy shelling, disease and dangerous construction work still claimed the lives of more than 100. Given this loss, I cannot help but feel the absurdity of war.