Ten minutes in the tsunami

"I told my grandma, 'We have to leave. A tsunami is coming!'"

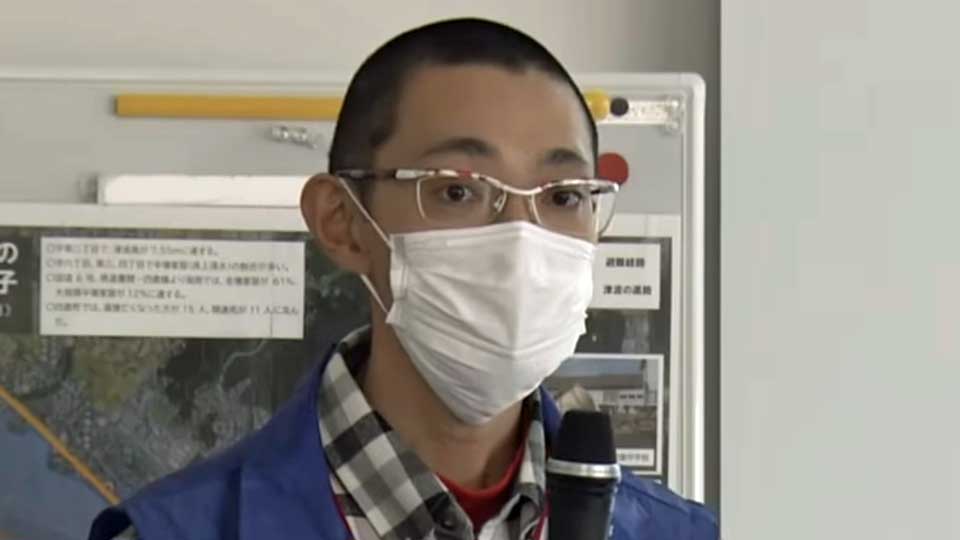

Ono recounts his experience to the crowd that has gathered for his session one Saturday afternoon in late February. His hour-long presentation is entitled "Making the Most of a Life Spared."

Ono was aged 20 at the time, just a week away from his technical college graduation. His story starts at home: A quiet afternoon with his 80-year-old grandmother is suddenly interrupted by a magnitude 9 earthquake. The terrifying shaking lasts more than three minutes. There is no doubt in his mind that a tsunami will follow, but his grandmother refuses to leave. Her back hurts, and she believes the two-meter seawall in front of their two-story house will keep them safe.

So, despite the impending danger, Ono decides to stay with his grandmother. Looking out from the second story, he keeps his video camera fixed on the raging ocean, right up until it crashes into his home. By then, it is too late to escape.

The water reaches waist level. Ono manages to hold on to his frail and bent grandmother. They stay that way, clinging to each other, 10 long minutes in the furious sea.

When the tsunami finally recedes, Ono and his grandmother are alive. He steps outside and is shocked to find that his house is the only one left standing along the Toyoma beachfront where he grew up. In his neighborhood, 85 people have died.

Ono tells the museum visitors: "Thinking of the people who tried to escape but died, I can't say I feel happy about my situation."

For years, Ono kept his footage of the tsunami to himself. He suffered from survivor's guilt. But now he feels a pressing need to share his experience as a warning to others.

When the Iwaki 3.11 Memorial and Revitalization Museum opened in May 2020, Ono decided it was time to speak up. The video camera he had used during the tsunami was damaged by seawater, but the data inside — his clip of the tsunami — was salvaged.

Even now, watching the video clip is difficult for Ono. But he endures the frightening scenes to convey the importance of disaster awareness.

"With smartphones and social media, it's very easy and tempting to want to capture what's happening around you even in a dangerous situation. But the first thing one should do is to escape to a safe place," urges Ono in an interview with NHK World.

Steps towards recovery

After the tsunami and the ensuing nuclear disaster, some people moved out of Fukushima Prefecture. But the disaster made Ono even more determined to stay.

"Even though everything around me was in total ruins, that very night I thought to myself, 'What can I do right away — tomorrow — to be able to come back and live here again?'," he relates.

After graduating as a mechanical engineer, Ono gave up on a childhood dream to join a major automobile maker. Instead, he chose to join a local battery firm so he could stay in his hometown and contribute to its recovery.

As a first step, Ono confronted his fear of the ocean to help with beach cleaning efforts in the hope of bringing the tourists back to Toyoma beach, once known as a surfers' paradise for its barreling waves.

"Around February 2017, I stepped onto the beach for the first time since the tsunami. Before that, I always kept my distance; the sea frightens me," he says.

Since then, Ono helps with a beach cleanup every Sunday.

Storytelling on wheels

Last spring, Ono started a new form of storytelling — on two wheels. He has been an avid cyclist since his school days and is a qualified cycle tour leader.

"As a kataribe, I also want to be able to bring to life the scenery and streets I knew before the disaster. That's something that's hard to do within the confines of the museum. Cycling is one way I can make that happen."

The weekend before this year's March 11 memorial, Ono leads a group on a 16km, half-day tour of the Toyoma district he grew up in.

This is the 10th such tour that Ono has organized in collaboration with "NORERU?", a local cycling promotion group.

The tour follows the Nanahama cycling route tracking the Iwaki coast. One section runs along seawalls that stand more than 7 meters high.

The barrier allows people to stay connected with the ocean while protecting them from its fury.

Iwaki 3.11 Memorial and Revitalization Museum

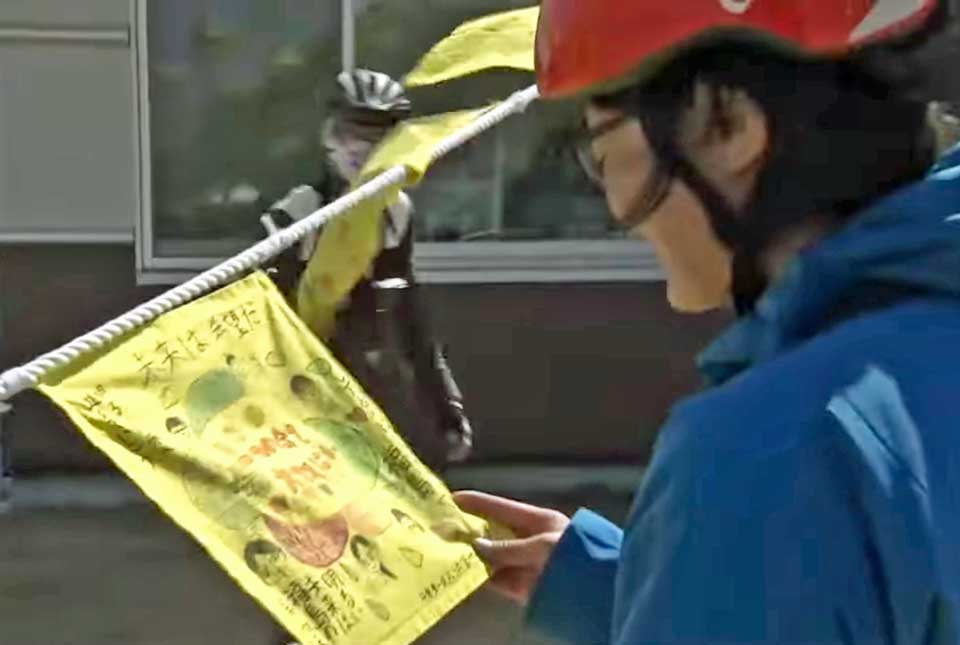

First stop for Ono's group is the Iwaki 3.11 Memorial and Revitalization Museum. Out front is a display of yellow handkerchiefs, each one bearing a message of hope for recovery from visitors to the museum, and people from the surrounding community.

Terazawa Asaka, coordinator at the "NORERU?" Cycling Culture Promotion Center, notes: "The messages from the kids really get to you. 'Treasure every life. The future is hopeful.' It's so true!"

Shioyazaki Lighthouse

Back on their bikes, Ono leads his group to the Shioyazaki Lighthouse, a local landmark. It has been watching over the port since 1899. Climbing the lighthouse is part of everyone's childhood memories — including Ono's. The 2011 earthquake shattered every window ... and the lighthouse went dark for eight months. It reopened to visitors in 2014.

Toyoma Beach

Ono also shows his group the stretch of beach where he grew up, and the exact spot where he filmed the tsunami from the second floor of his home. Surfers used to flock here during summer.

Toyoma Cenotaph

Not far away, at the Toyoma Cenotaph, they pause for a moment, silently paying their respects for the lives lost in the area.

Toyoma Park

Moving on to Toyoma Park, the cyclists are shown what's in place to save lives when the next tsunami strikes. The park, located 24 meters above sea level, is a designated evacuation zone. It's equipped with an electricity generator, emergency toilets, a stock of survival food and other necessities.

Café Diner Kyu-Ichi

For lunch, Ono invites the group to savor a local seasonal specialty — anglerfish hotpot. Café Diner Kyu-Ichi uses seafood caught off the nearby fishing port. The café re-opened for business in 2019 — the first shop to move back to the Toyoma neighborhood after the disaster.

Toyoma Junior High School

Ono's junior high school used to be located on the seafront. It was demolished and built further inland after the disaster. Ono's old school photos are the only tangible reminder of the surroundings he once took for granted. Fortunately, the albums managed to stay afloat on his bed during the tsunami.

The tour is over, and the cyclists dismount. Before they leave, Ono shares his thoughts on his hometown's recovery. "I'm not sure if we can say that we've fully recovered from the disaster but as long as I'm alive, with these hands, my work, my skills ... I'll do whatever I can, bit by bit, to help my community and society. I would like to be able to treasure the time spent with every person, to be able to take a leisurely bike ride with friends old and new, and to deepen our understanding on a shared road trip."

For Ono, the road to recovery is as much about the journey as the destination — and it's a journey he wants to share.