Onboard a bus to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, I gaze out the windows as we travel through what's called the "difficult-to-return" zone. There are abandoned houses on the verge of collapse, and weather-beaten shop fronts. Some neglected buildings remain, but many have been demolished, leaving vacant lots.

The last time I visited here in 2017, the main challenges in the decommissioning project were high radiation, and the mounting volume of contaminated water. I have returned to check progress.

Fewer workers

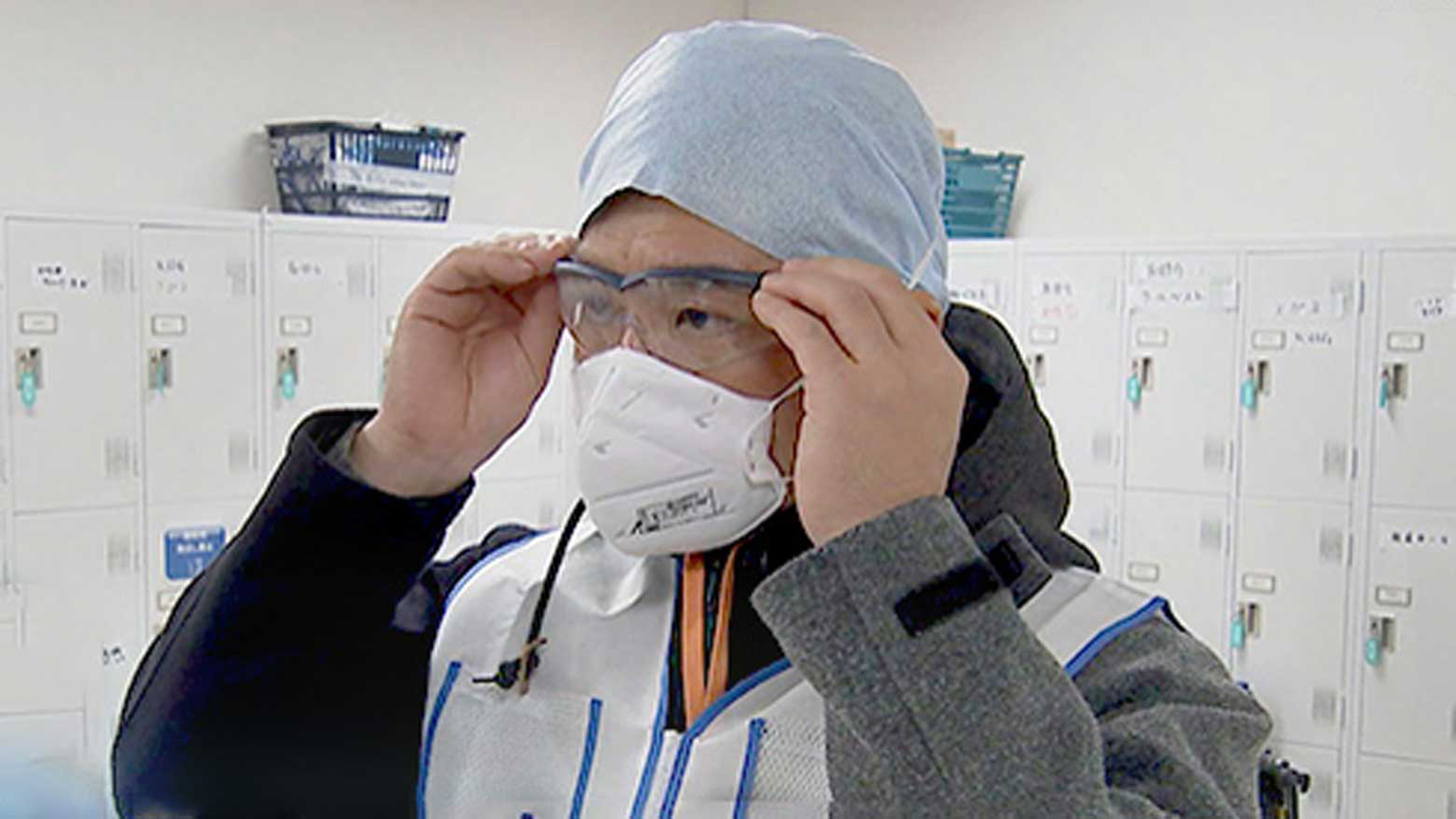

After completing a rigorous entry process, I enter the premises on foot. I am immediately overwhelmed by the vast reduction in the number of workers. Last time I was here there were approximately 7,500 people every day. They wore full face masks and head-to-toe protection gear, moving busily around. Rest areas were crowded. But it's much different now.

Ota Hideto, from the public relations department at plant operator Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), explains: "When radiation levels were high, the staff had to work for shorter periods and take turns working, to limit exposure. As the clear-up and decontamination progressed, radiation levels lowered, so we no longer need to carry out 'human wave attacks.' Now, the staff can work more methodically and safely."

There are currently 4,000 workers on site each day, half of what there used to be.

What to do with the water

Problems surrounding water accumulation at the plant have also changed drastically.

Inside the nuclear reactor buildings is a mixture of groundwater, rainwater, and water used to cool melted nuclear fuel. That water is highly radioactive. Currently, 100 tons accumulates each day.

In 2014, the treatment of contaminated water using ALPS (Advanced Liquid Processing System) began. Early on, there were some incidents, including the leaking of highly contaminated water from a tank.

ALPS purifies the contaminated water, removing most of the radioactive materials with the exception of tritium. So far, 1.32 million tons of what's called treated water have been produced.

More than 1,000 storage tanks full of treated water occupy large areas of the vast site. Capacity is already at 96 percent, and according to TEPCO, at the current rate it will be full by the northern hemisphere autumn.

TEPCO, following government policy, plans to release the treated water into the sea, after diluting it further with seawater. This will lower tritium levels to less than one-fortieth of the national safety standard, and one-seventh of the World Health Organization standards for drinking water. Authorities say the discharge will take place "around spring through to the summer."

But people in Japan are divided over the plan. Concerns over the possibility of reputational damage, especially for the fishing industry, are one factor.

The government and TEPCO are trying to raise awareness about the safety of the treated water, in an effort to gain understanding and trust, and to be transparent about the plan.

Breeding fish in treated water

Inside a building in a corner of the plant site, large water tanks several meters square are lined up in a row. It looks like an aquarium, and in some ways it is. This is where TEPCO is farming fish: 400 flounder to be precise.

The facility aims to demonstrate the safety of the diluted water it plans to discharge into the ocean. The fish are kept in two different tanks: one filled with treated water at the standard concentration for discharge, and the other with ordinary seawater. The idea is to prove there is no difference in growth patterns and that the tritium will not be absorbed.

The fish-rearing project is being streamed on YouTube and via Twitter. According to staff, there is no difference in the rate of growth, or death and illness. So far, they have confirmed that tritium is not accumulating in the fish. They obtained similar results from abalone raised in a separate tank.

I ask why the plant operator has gone to the trouble of raising living creatures to promote the safety of treated water. Yamanaka Kazuo of TEPCO's Fukushima Daiichi Decommissioning Promotion Company, is in charge of the breeding program.

"In the field of nuclear energy, we tend to explain too technically," he says. "That doesn't convey the message to the general public and makes them wary. The most effective way to reassure the public is to show them that creatures such as flounder and abalone live healthily in that water, although we know it is a risky approach.

"In my 40 years at this company, I never dreamed we would raise flounder at a nuclear power plant," he notes.

Extracting fuel debris

The dosimeter on the minibus I travel in at the site shows a reading of 0.3 microsieverts when we are 500 meters from the reactor building. The reading rises sharply as we approach Unit 1 and as we get within 100 meters the radiation level rises to 30-40 microsieverts. Molten nuclear fuel debris lays behind the concrete walls shattered by the 2011 accident, and twelve years later it still emits intense radiation.

Preparing for debris removal has progressed steadily, including photographing and testing sediments that are considered debris. However, the crucial extraction operation has been twice postponed due to a need for improvements to the robot arm and damage to equipment that prevents radioactive materials from escaping.

Preparations are now underway for the extraction to occur during the second half of the next fiscal year. TEPCO public relations official Ota explains the process. "The first step is to remove the spent fuel, then we can remove the fuel debris. There are still various obstacles along the way. We are reorganizing the process to lower the risk and ensure it is safe, which will take time, but we are doing our best."

When I visited six years ago, TEPCO officials were able to photograph the inside of the containment vessel for the first time. We hoped then that the plan for the fuel extraction would go smoothly. Since then, high radiation has since hampered the process, forcing a review.