Defining the "typical household”

According to the Bureau’s definition, a "household" consists of one or more people who share their residence and live off a common budget.

The bureau started using the term "typical household" in the 1970s in its survey on household income and expenditures, a closely watched economic indicator. The Finance Ministry also uses the concept of a “typical household” as a model for calculating the impact of tax or social security reforms.

"Families consisting of a father who is a salaried worker and a stay-at-home mother with two children were the norm in Japan during its era of high economic growth and urbanization (in the 1970s)," says Shungo Koreeda of the Daiwa Institute of Research (DIR). "The government and businesses thought the most realistic way to analyze Japan's situation and plan systems for the future was to base their discussions on such model households."

Changing standards

But the term “typical household” used for so many years diverges from the social reality of today.

In 1974, right after the end of Japan's high-growth years, families comprising one breadwinner and a homemaker were the most common kind of household types at 14.6% of the total, according to an estimate by the Daiwa Institute of Research. But they slipped to 2nd place with 9.7% in 1988 during Japan's bubble economy, and to 9th place with 4.6% in 2017.

In light of such changes, the Statistics Bureau dropped the term "typical household" in 2004. Now it defines such units as "a 4-member household with one earner," a change in wording that underscores an awareness that such households are no longer "typical."

Households become more diverse

The shift is marked by a steady rise in the number of single-person households. In 2017, units with one person with no job were the most common group, accounting for 16.9% of the total. Households consisting of a single earner stood at 15.6%. Together, they made up a third of all households in Japan.

As for the first group, the aging population means more households are living off pensions, Koreeda says. And many of the "single earners" are women who have entered the workforce and marrying later in life. An increase in the number of divorced couples is another factor.

In the meantime, the number of households with no earners are increasing. They accounted for a mere 6.8% in 1974, but rose to 32.3%, nearly a third, by 2017.

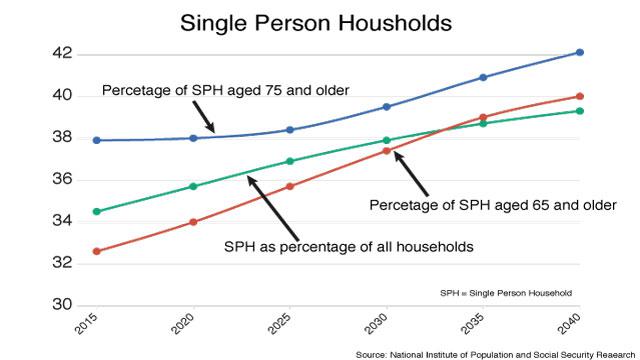

The trend is certain to continue -- and at a faster pace. The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research estimates that the ratio of single-member households is expected to reach 39% by 2040. The institute also projects that 40% of households headed by people aged 65 or older will become single member units. It says 42%. will be headed by people aged 75 or older.

The household concept under review

Koreeda says the current social security and tax systems were devised using "typical households" as a model, and so many of their measures are out of synch with the country's demographic profile.

"For instance, the government gives a tax break for a salaried worker whose spouse is a full-time housewife but officials have debated scrapping the measure, because there are now more double-income couples,” he says.

As Japan's population ages, the birthrate declines, and the population becomes more diverse, officials may soon need to pay a lot more attention to policies that meet the needs of people living alone.