Investigation Spillover

The university's manipulation of exam scores first came to light in a separate investigation into bribery at the institution. A former education ministry official was alleged to have offered favors to the university to ensure his son passed the entrance exam.

The university set up a committee to investigate and it released its findings on Tuesday. It noted that the alteration of scores started with the first stage entrance exam.

The first exam is marked for a total of 400 points. Investigators found that the university had padded the scores of 6 applicants, awarding a range of 10 to 49 points, including for the son of the ministry official.

They also found that 13 applicants had points added to their first exam scores last year.

They said the practice with the second stage exam was to mark down all scores by 20% , then give male applicants who were taking the exam for the first time or had failed in the previous 2 years an additional 20 points. Men who had failed in the previous 3 years got an additional 10 points.

All women applicants and men who had failed in the previous 4 years got no additional points. A university director has publicly apologized for the behavior.

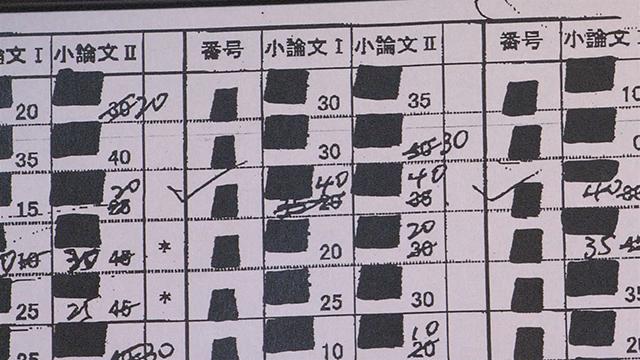

NHK has obtained a list of the scores altered in the second exam in 2014. The original scores are crossed out. University officials said the manipulation of scores at the second stage started in 2009 or earlier.

The investigating committee said changing the scores on the second exam alone wouldn't have helped those applicants the university was asked to admit. It said that's why the university started changing scores in the first stage as well.

A past chairman of the university board and a past president are also alleged to have accepted money and goods from successful applicants.

A 21-year-old male applicant who had failed to gain entry in the last 3 years expressed his anger. "I always wanted to be a physician," he said. "I'm upset that I was not evaluated fairly."

A woman applicant who failed twice was infuriated by the news. She is now on the faculty of medicine at a national university. "I wondered at the time how it was possible for anyone to pass that exam," she said. "Everyone taking the exam should have been on an equal footing."

Debate About Sexism

"These irregularities are a betrayal to society," said one member of the investigating committee. "This can be viewed as serious discrimination against women," he added.

A school source gave the reasoning behind the misconduct, saying university officials were worried about the ability of affiliated hospitals to keep running if women doctors quit after graduation to get married and have children.

Professor Tomokazu Haebara is head of the University of Tokyo Center for Research and Development on Transition from Secondary to Higher Education. He says the altering of scores "should never have happened." He emphasized that a woman applicant got zero even if her score was 25 points higher than her male counterparts. He said the practice "tipped the gender balance significantly."

Meanwhile, a survey suggests a majority of women doctors understands why the university did this. A medical online media outlet surveyed 103 women doctors. 18% said they fully understood why the university engaged in the practice, and 47% said they understood to some extent. Only 35% said they had no understanding at all.

One respondent said the hospital she works at wouldn't be able to keep up with demand if it weren't for male doctors. Another said she has thoughts of quitting her job because long hours have led her to have repeated miscarriages.

The representative of a women doctors' association, Ruriko Tsushima, says the backdrop to this scandal is the severe working conditions of the medical profession in the country.

"I don't think it's a problem with women, it's a problem with how doctors work in general," she said. "In order for women to be able to continue working, male doctors need to change the way they work and create an environment where they can work together."

Tsushima is urging hospitals to adjust their working styles so medical professionals can finish work earlier.

A health and labor ministry panel came up with a set of measures in January to help women doctors balance work and child-rearing with shorter working hours.

Reaction Overseas

Embassies in Japan have been reacting to the scandal online. The French and Finnish embassies are urging Japanese women to come to their countries to study medicine.

The French Embassy posted a message on its Twitter account saying that women account for more than 60% of all medical students at French universities.

The Finnish Embassy tweeted that Finland has the world's third-highest percentage of female doctors, and that the country promotes flexible working arrangements and good work-life balance.

The issue has also been getting wide coverage in the foreign media. French news agency AFP says Japanese women are highly educated but the country's notoriously long working hours force many to quit once they start a family. It says while Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is promoting women's participation in the labor force, progress has been slow.

Doctors' Working Conditions

Susumu Morita, general secretary of the Japan Federation of Medical Workers' Unions, says the problem is not only with Tokyo Medical University. He says Japan suffers from a severe shortage of doctors, citing OECD data. The data shows there are 2.4 doctors for every 1,000 residents, compared to an average 3.4 for other OECD member countries in 2015. Japan is also near the bottom in terms of percentage of female doctors, with only 20.3%, compared to an OECD average of 46.5%.

"In many countries, more than half the doctors are female, which means Japan has been avoiding having men and women share that role because of the lack of doctors overall," Morita says. He adds that the problem is not about how women doctors work, but about the working environment overall in Japan.