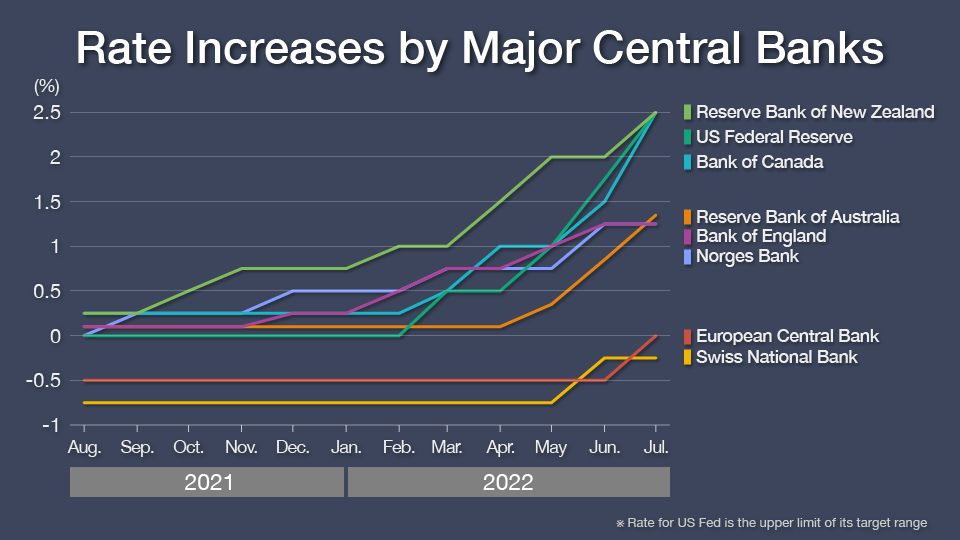

Central banks on a tightening trend

Across the world, from Canada to the Philippines, monetary authorities are aggressively raising rates in an effort to cool inflationary pressure.

The US Federal Reserve began raising the federal funds rate at its policy meeting in March. Since then, the Fed has rapidly accelerated the pace of its hikes, opting for a 75-basis-point shift for the second time in a row in July.

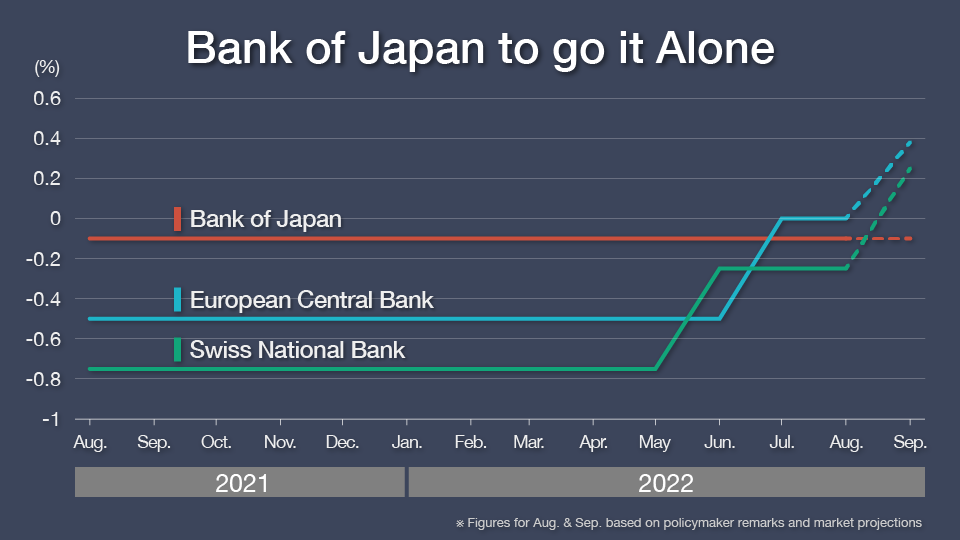

End to negative interest rates

Even central banks that have kept their key rates in negative territory for several years are embracing the tightening trend.

The European Central Bank at its July meeting raised its key rate for the first time in 11 years, from -0.5 percent to 0 percent. It broke its own guidance for a 25-basis-point move, opting for 50 instead, bringing the eurozone's policy rate out of negative territory in one decisive stroke. The ECB has signaled more rate rises are on the way, the next one likely by 25 or 50 basis points in September, as the region grapples with record inflation.

The Swiss National Bank, which has spent years trying to halt the rise of its currency, also hiked its rate by 50 basis points. The move in June brought the policy rate up from -0.75 percent to -0.25 percent.

The bank has signaled its next rate rise, which will come by September, will take the key rate into positive territory. One Swiss newspaper is forecasting another 50-basis-point hike but writes that insiders have not ruled out 75 if inflation runs rampant.

'Reverse currency war'

Mizuho Bank Chief Market Economist Karakama Daisuke says central banks are raising rates in a bid to strengthen their currencies. "The prices of natural resources and commodities have gone up. But a strong currency can bring down the cost of imports, so monetary authorities around the world are tightening policy to raise the value of their legal tender."

Nomura Research Institute Executive Economist Kiuchi Takahide calls the phenomenon a "reverse currency war." He explains, "Due to unexpected rampant inflation, import prices are soaring, so countries want to make their respective currencies stronger. It's the opposite of what used to be the global norm: trying to weaken their legal tender to boost exports, and thus, the economy."

Bank of Japan going it alone

The Bank of Japan, on the other hand, is defying the global trend and maintaining its ultra-easy position. Policymakers signaled at their July 20-21 meeting that they have no plans to change that stance. That means for the foreseeable future the central bank will keep the short-term interest rate at -0.1 percent and continue to make unlimited purchases of JGBs (Japanese government bonds) to keep long-term rates near 0 percent. The decision puts the BOJ on track to be the only central bank with its key interest rate in the negative.

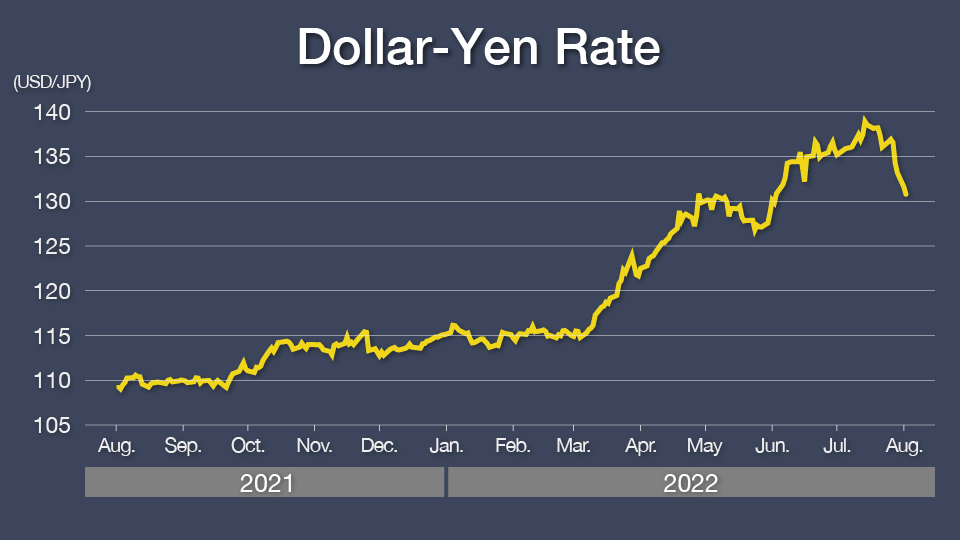

Yen sell-off

The BOJ's divergence from other monetary authorities has had a serious impact on the yen. Japan's currency has declined about 15 percent against the dollar since the US Federal Reserve started raising rates. Karakama notes, "If things go as the central banks are signaling, Japan will be the only country with negative interest rates, so that gives people a good reason to sell the yen."

Weaker yen making Japanese poorer

Karakama says the weaker yen is having serious consequences for Japanese households. "The weaker the yen becomes, the more Japan has to pay to buy wheat, oil and all other resources. The income of Japanese people will flow out of the country and they will become poorer."

He offers an example: the iPhone. Apple devices became more expensive in Japan from July 1. The price tag on the newest smartphone went from 98,880 yen to 117,800 yen, a near-20 percent jump. "The price increases are unique to Japan: it's not happening anywhere else," Karakama explains. "The move reflects the yen's devaluation."

Consumers are feeling the pain, so much so that BOJ Governor Kuroda Haruhiko had to apologize after his remark on "households accepting price increases" sparked outrage.

Inflation in Japan is not being led by robust demand, but by higher import costs and a weaker yen, so it's not boosting corporate earnings or leading to wage growth. Kiuchi warns the negativity will likely continue unless the BOJ changes course. "If rate differentials between Japan and other countries widen, that will lead to a weaker yen, which in turn will lead to higher prices without salary rises. It'll be a vicious cycle."

BOJ defies the risks

Despite the backlash, Governor Kuroda is standing fast. He reasons that monetary easing is needed to stimulate Japan's still-weak economy, which continues to feel the impact of pandemic restrictions.

Kuroda and his fellow policymakers feel the best way to do that is to keep borrowing costs low, which can be achieved by buying up government bonds to keep long-term rates near zero. However, Kiuchi points out this is becoming tougher as the BOJ's counterparts take their policies in the opposite direction. "Until recently, the BOJ was able to control rates because there were no big changes in the external environment. However, as rates in the US surged, keeping rates low in Japan became difficult, so the shortcomings of this policy are being highlighted."

In fact, Kiuchi believes the BOJ's bond-buying program is unsustainable. The central bank now owns over half of all JGBs. Kiuchi cites two serious risks for the Japanese economy if the buying continues:

Risk 1) Turmoil in JGB market

"When the Bank of Japan purchases large amounts of JGBs, there's less liquidity in that market," Kiuchi says. "When trading volume is low, a small move can drastically impact the market. I believe the BOJ is aware that it is distorting the bond market and was cutting back on bond purchases until recently. With rate differentials with other countries widening, though, policymakers had no choice but to ramp up buying in order to forcibly lower long-term rates. However, the central bank cannot keep making unlimited purchases of JGBs."

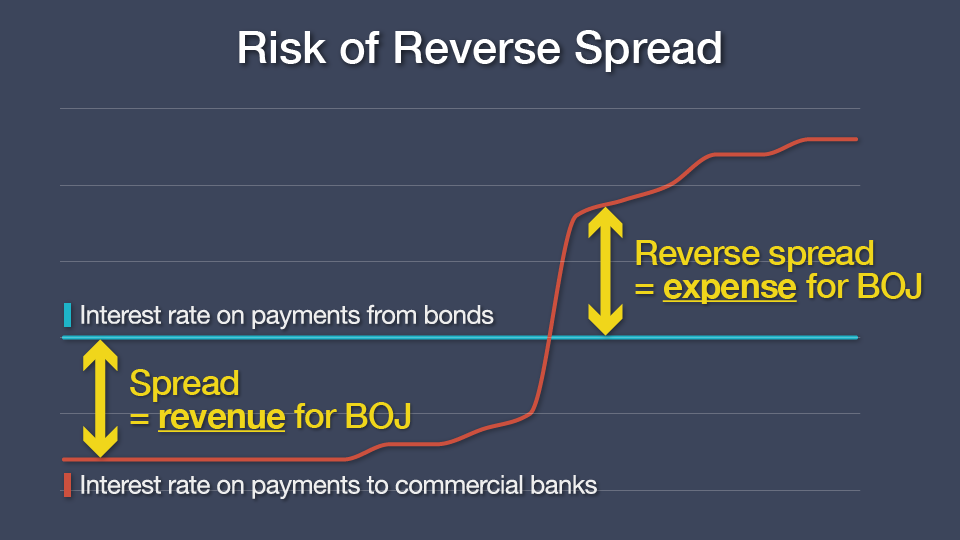

Risk 2) BOJ insolvency

"Large-scale bond purchases mean a bloated balance sheet for the BOJ," Kiuchi warns. "This will be problematic when it eventually raises rates. Currently, the central bank is paid the yield on the JGBs it owns, while it also pays interest to commercial banks that park their cash at the BOJ. The difference in those rates allows the BOJ to profit. However, once the BOJ hikes rates, the spread will reverse, and the central bank may have to pay more to commercial banks than it receives from the bonds it owns."

This situation arises because bonds have a fixed interest rate upon issuance. The interest payments from the bonds the BOJ owns will not increase due to rate hikes, but the interest on payments it makes to commercial banks will.

The added expenses from the reverse spread will weigh on the central bank's finances – and also on its credibility. Kiuchi is concerned that "continued and excessive bond-buying could hit the BOJ's finances and even cause insolvency."

Another factor that may reduce confidence in the BOJ is paper losses. Once rates are raised, the market value of previously issued rates with interest fixed at lower levels will fall. As the BOJ owns nearly 4 trillion dollars' worth of JGBs, their devaluation will lead to substantial unrealized losses.

Impact of unhealthy balance sheet

Kiuchi says if the BOJ falls into the red, there will be serious consequences. "If the central bank becomes insolvent, confidence in the currency will be lost. The yen could weaken drastically, prices may surge, and the economy will take a hit."

Karakama, on the other hand, is skeptical about whether such a situation would lead to a devaluation in the yen. "The Swiss National Bank used to sell unlimited amounts of its currency, the franc, to keep its value from getting too high. However, it gave up at one point and the franc's value rocketed. The SNB was insolvent at the time, so in this example, the central bank's balance sheet did not influence currency value negatively." Regardless, Karakama says, he is watching the situation very closely. "Central bank insolvency would make a catchy headline, so it may lead to a sell-off of Japanese assets."

Stakes getting higher

With inflation soaring, the painful consequences of monetary policy are coming sharply into focus for people across Japan. The worsening situation is prompting questions about how long the Bank of Japan can continue to ignore the global move away from easy money.

Next BOJ chief may chart a new course

Karakama points out that the best time for the BOJ to change course would be with a new leader. Kuroda's term is set to end in the spring of 2023, at which point someone with a different philosophy could be in the running to take over. "Governor Kuroda raised eyebrows when he said households are accepting price increases in June. That comment caused a big public outcry. It even made people who are not usually interested in monetary policy look critically at the central bank. The next chief will be chosen in this atmosphere, so they will likely be someone who is not too keen on continuing easing. With such an appointment, the BOJ may be in the right place to shift its policy."

One thing is beyond doubt: The next central bank governor will face an unenviable decision. To press on with the BOJ's vast easing program risks inflicting more pain on consumers. However, scaling back the policy will be a high-wire act, with one false step potentially crippling the bank's finances and having runaway consequences for the economy.