Unsanitary, cramped conditions

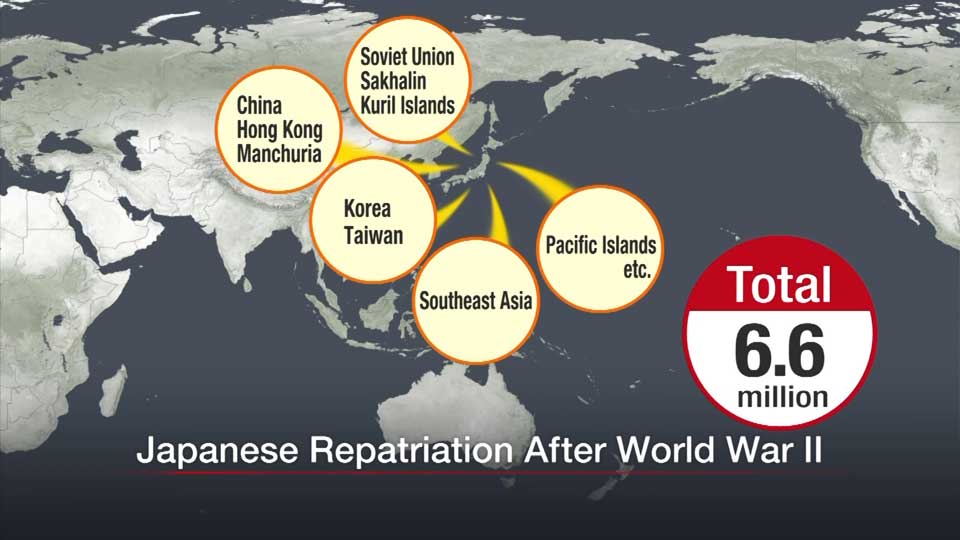

Cholera broke out in many of the ships that were commissioned to repatriate more than 6.6 million Japanese people at the end of World War Two. Footage believed to have been filmed by the United States-led General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ) depicts that time. Vessels were packed with soldiers and civilians returning from the Asia-Pacific region.

Onboard conditions were unsanitary and allowed for the spread of infectious diseases such as cholera, a sometimes fatal affliction that can cause diarrhea, vomiting and dehydration.

Japan's occupiers at GHQ enacted strict quarantine measures that critics maintain led to more deaths – and more suffering. Ito Kyoko, 83, says she was repatriated from Manchuria on a ship that had a cholera outbreak.

"As more people lost their lives each day, I worried that I might also die tomorrow. There was no place to sleep. There was nothing to eat, and nowhere to be alone. It was hell, actually," she recounts.

Authorities censor growing crisis

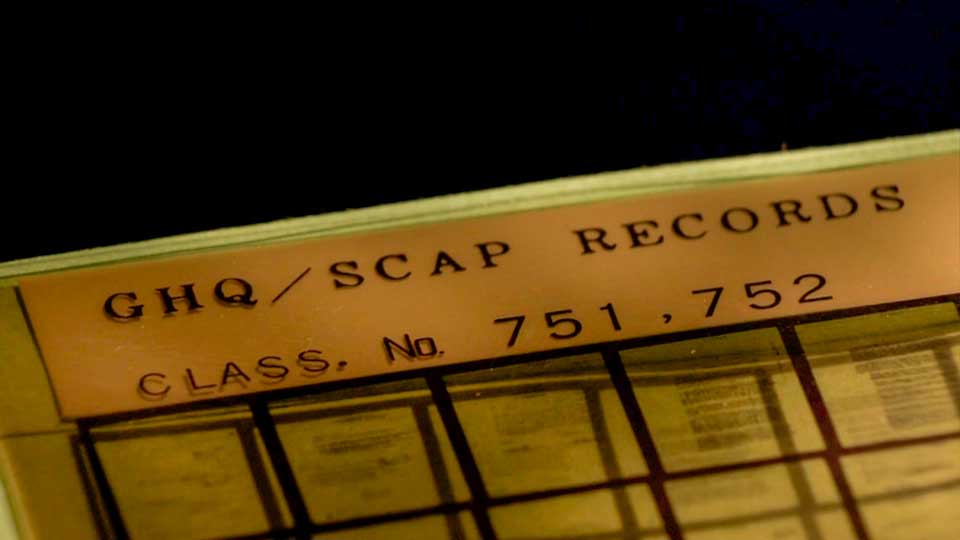

As the tragedy unfolded it was being hidden from the public. NHK has unearthed confidential GHQ documents that show newspaper coverage was censored.

"Mothers are weeping over their babies who died of malnutrition," read one redacted description. "The ship is nothing short of a picture of hell."

British scholar Christopher Aldous, Professor of Modern International History at the University of Winchester, has analyzed the unpublished accounts.

"They were worried, I suppose, of anti-American feeling within Japan if the true conditions on those ships were accurately depicted. So it was about controlling the message so as to prevent that," he says.

"In fact, things were a lot worse, of course, than was presented in the censored newspapers," Aldous surmises.

Senior official recalls 'terrible situation'

The quarantine orders were issued by Colonel Crawford F. Sams, the chief of the GHQ's public health and welfare section. His aim was to protect allied service personnel, as well as the Japanese public.

Reflecting many years later, he said: "It was a terrible situation and we were very lucky in controlling it. I was one of the six men, as he (Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, General Douglas MacArthur) called us, who rebuilt Japan."

Officially, the measures that Sams put in place were portrayed as a successful quarantine effort. But the Japanese side viewed it differently.

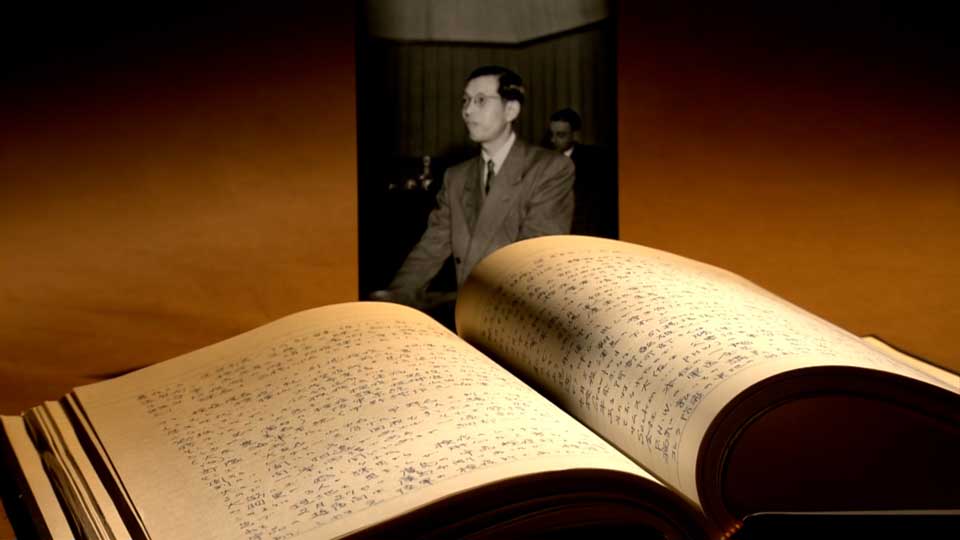

NHK has obtained handwritten documents from Yamaguchi Masayoshi, then a senior official at the Ministry of Health and Welfare. He wrote about his frustration: "Requested permission for crew to land, but it's hard to get permission. I was surprised by the difference in response even if we were under occupation."

Passengers in perpetual quarantine

At the time, the quarantine period for people infected with cholera was five days, based on an international treaty. But GHQ insisted on 14 days. Moreover, the quarantine period for ships with new infections was continually extended.

In some cases, passengers were forced to remain on board for about 40 days. Yamaguchi asked Sams if the quarantine could be shortened.

"We persisted as much as possible," wrote Yamaguchi. "We wanted to let everyone come ashore. But the GHQ was adamant in saying no. They would not allow them to land in order to protect their troops from infectious diseases."

It is believed the prolonged quarantine caused cholera to spread to healthy passengers. Official records show that 230,000 people were quarantined on 114 ships. More than 1,000 were infected with cholera, and 167 died. But the exact figures, including the number of people who died of malnutrition while waiting to be let off, could be much higher.

"People became sick one after another. They took unthinkable measures with little respect for human rights. Regardless of the administration's occupation, I was in charge of quarantine, and I felt as if I was being hurt," wrote Yamaguchi.

"It is deeply regrettable that many compatriots lost their lives, right on the doorstep of their home country," he continued.

Too weak to eat

Passenger Ito was on a ship that was forced to remain offshore for 40 days. During that time, her three-year-old brother died. She says she is haunted by the memory.

"My younger brother said at the end that he wanted to eat noodles. So, my mother asked the crew to share what they had, even if it was one or two strands. She gave him two or three noodles and put them in his mouth, but he could no longer chew. He seemed to move his mouth a few times, but then he died."

Analysis by NHK WORLD correspondent Shirakawa Marina

Many people in Japan do not know about this tragic episode from the end of World War Two because of the media censorship.

Also, there is a reluctance in Japan to discuss infectious diseases, both then and now. Amid the coronavirus pandemic, many people simply don't want to reveal that they are, or have, been infected.

And although there is no simple comparison between the current pandemic and what happened with the cholera outbreak, there are some lessons to learn.

There is always the risk that human rights will take a backseat when it comes to quarantine. Infected people must isolate to protect others. But that in itself presents difficulties, and some people in Japan have died at home without receiving proper medical care.

The coronavirus has dominated our lives for more than two years. It is important to keep in mind that we humans tend to forget about our struggles once they are over. And it will be crucial to properly evaluate the pandemic – not just for officials and researchers -- but for all members of society.

Read more about the cholera quarantine here: