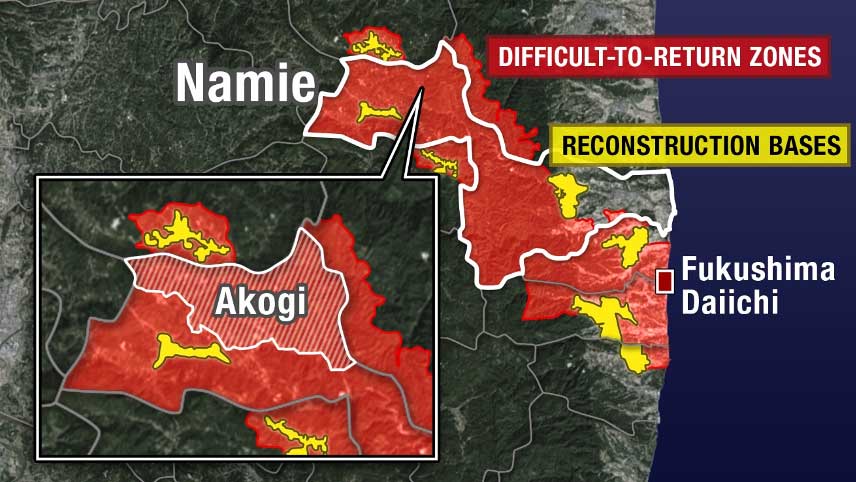

Almost every month, Konno drives more than 100 kilometers from his evacuation housing to his old hometown in Fukushima Prefecture. The 77-year-old is the community leader of Akogi, one of the most contaminated areas in what the government has termed a "difficult-to-return" zone.

He needs to apply for government permission each time he visits and is not allowed to stay overnight.

Konno has made it his mission to keep the displaced residents informed of radiation levels around their homes. He visits every one of the 80 households, dosimeter in hand, and sends the readings to the owners.

The readings vary significantly from house to house, but most are still too high for the government to lift the evacuation order.

"Many people are worried about their homes," says Konno. "I realize that informing them of radiation levels won't give them peace of mind, but I think it's better to know than not know."

The 'blank space'

Some parts of the "difficult-to-return" zones have been declared "reconstruction bases" and are the focus of the decontamination work. The government plans to lift evacuation orders for those areas this year or next. Elsewhere, though, very little has been done. The locals derisively refer to these areas as 'the blank spaces.' Konno's district is one of them.

Last year, the government set a new target for allowing people to move back to those "blank spaces": the end of this decade. Even if they hit that deadline, it doesn't mean the towns and villages will spring back to life. The authorities are only planning to decontaminate the specific areas to which people plan to return, and the displaced residents fear the result will be so patchy that it still won't be a place they can settle in again.

Documenting a hometown

Immediately after the nuclear accident, a government official said something that still haunts Konno:

"You may not be able to go back for 100 years if nothing is done."

He worried that the government would take so long the town would simply disappear from maps—and memories. So, eight years ago, he started working on a record of his district for posterity.

First, he gathered testimonies from displaced residents, including their experiences after the nuclear accident.

"I wanted to show everyone my work when it's finished," Konno says. "But some are already gone."

He enlisted other locals to dig into Akogi's history, and one thing he discovered got him thinking.

The region experienced several famines caused by natural disasters, the worst one in the 18th century.

"People survived those famines," says one of Konno's fellow researchers. "But no one remains in Akogi after the nuclear disaster. I can't get over the gap between these two outcomes. It's simply absurd."

To descendants yet to come

Konno will release his research as a book later this year. It will feature more than 700 pages of radiation monitoring data, residents' testimonies, and the history of the district.

He's titled it 'To Our Descendants 100 Years from Now.'

"My generation may be unable to return home. We're too old. But I hope that our descendants who read my book will return to this beautiful area and farm the land again."

Plum tree buds herald spring. Konno hopes his chronicles will open a new chapter in the history of Akogi.

Watch Video 03:35