Hellish memories

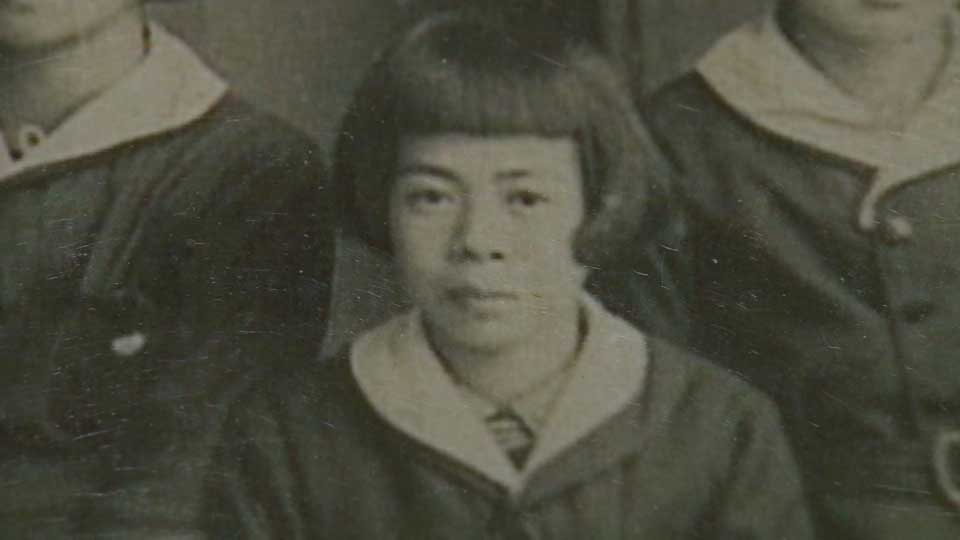

Oka Nobuko was in Nagasaki on August 9, 1945, the day the US dropped an atomic bomb on the city. For most of her life, she avoided talking about her experiences as the memories were too painful.

Last year she finally broke her silence to deliver a speech at the annual ceremony commemorating the date of the bombing.

"When I stood up, I was immediately knocked down and I lost consciousness," she recounted. "When I woke up, I didn't know where I was. Pieces of shattered glass were lodged in my body."

Oka was a 16-year-old nursing student at the time and helped treat other victims at a first aid center.

"No treatment was possible in a lot of these cases," she said. "There was flesh dangling from exposed bone. Some people jumped off buildings to kill themselves because they couldn't endure the pain any longer."

She described the scenes as "hellish" and said she suffered severe headaches every time the memories returned. For this reason, she always avoided going to the area where the first aid center was located.

Time to speak

In a letter to a close friend three years ago, Oka wrote of her worries that her memories and those of other hibakusha would soon be gone.

"The hibakusha are getting older and someday all of us will be gone," she wrote.

Estimates put the number of living hibakusha at around 127,000, with an average age of 83.

This sense that time was running out is what motivated Oka to finally share her story last August.

"We, the hibakusha, will continue to share our experiences and call for the abolition of nuclear weapons. We will fight for peace."

Last November, three months after giving her speech, Oka died at the age of 93.

Inspiring other hibakusha

Fukuda Hakaru, a 90-year-old Nagasaki hibakusha, says hearing Oka speak inspired him to share his own story. He wrote her a letter, saying how much her courage had moved him.

Fukuda had gone to the first aid center Oka was working at to get medicine for his father, who was severely injured in the blast.

"I can still hear the screams of the patients," he says. "Doctors and nurses were running around to help them. It was a painful sight. It is very hard for me to talk about what I saw. The medical workers were the ones who saw up close the inhumanity of the atomic bombs."

Fukuda was 14 at the time. He did not suffer any serious injuries, but his father, who was working close to ground zero, died a month later.

"I'll never forget how I felt. I had to pick up his remains after the cremation, but I have no idea how I managed. The world needs to know that this is the kind of pain that an atomic bomb causes. It cannot be allowed to happen again."

Fukuda says he long felt he had a duty to share his story but avoided doing so because he was worried about the anti-hibakusha discrimination he and his family might face.

Many survivors and their families have had to deal with prejudice and discrimination over the years. Initially, little was known about the effects of radiation exposure, and some people incorrectly regarded it as contagious. The social stigma was especially serious when it came to marriage or work.

"The hibakusha continue to suffer today," says Fukuda. "That's yet another reason why we need to make sure this never happens again."

Preserving Oka's message

In December, a group of university students from Nagasaki hosted a virtual conference about the experiences of the hibakusha, speaking to high school classes about the stories they had heard from survivors.

One of these students was Kaji Misato, who spent a lot of time with Oka during her final days.

"Oka was with her mother and brother at the time of the bombing," Kaji said at the event. "As she stood up, she realized she was covered in blood."

Kaji spoke to Oka four times last year and recorded five hours of conversation. She said it was an eye-opening experience.

"The atomic bombing always felt like something in the past," Kaji says. "But after hearing her story, I started to feel a greater sense of attachment. She told us the war had robbed her of her youth and she wanted peace so the same thing didn't happen with the youth of today."

Every year on August 9, a siren rings out across the city at 11:02 AM, the exact time the atomic bomb exploded. Residents stop what they are doing to observe a minute of silence. But when Kaji visited the city center last year, she was shocked to see how few people were actually paying their respects.

About a month later, Oka was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Kaji met with her shortly after.

"She told me she was worried that once all the hibakusha are gone, their memories would fade as well," Kaji says.

She took her words to heart and decided to share what she told her with people even younger. The high school students who attended the virtual session said it was an insightful experience.

"Her vivid memories made me feel the horror of the atomic bomb," said one student.

"We cannot take peace for granted," said another. "We have to take care of the people who are close to us."

This year promises to be a crucial one for the abolition movement. State parties to the UN nuclear weapons ban treaty are planning to hold their first meeting to try to agree on specific actions. In the meantime, young campaigners like Kaji are ensuring that the stories from those who witnessed the horrors of 1945 are documented and heard.