Studies plagued by anxiety

Beatriz Reganassi Okumura dreams of becoming an interpreter for the many other Brazilians living in Japan. But her studies these days come with a painful 12-hour time difference.

“My class starts at 9 p.m. and [doesn’t] end until 1 a.m. I don't have a normal sleeping schedule. I wake up late and I don't have a lot of contact with my family,” she says.

When the 26-year-old enrolled in her course in October, she wanted to move to Japan. But the following two months have left her increasingly stressed and anxious. She’s now having second thoughts.

“I already told my teacher that I’m not continuing the online classes if they go on with online courses. Virtual study is only a temporary problem solver and we can’t have this forever,” she says. “I’ll drop out [of] the school and move on with my life here in Brazil.”

Foreigners banned again

Japan has virtually banned new entry for all foreigners. When Prime Minister Kishida Fumio first announced the strict border rules at the end of November, he called them necessary to “avoid the worst-case scenario.”

He went on to call the restrictions “temporary and exceptional measures” to ward off the Omicron variant.

That provided little consolation to the nearly 150,000 students who have found themselves locked out of the country, despite meeting all other eligibility requirements.

The situation is not new. Japan has been blocking entry for most foreigners since January 2021, save for a three-week window in early November when border controls were relaxed.

And despite initial suggestions that the latest suspension would end after a single month, Kishida now says it will run into early 2022.

Measures take ‘mental toll’

Nakano Ryoko, an assistant professor with Osaka University’s Center for International Education and Exchange, has seen first-hand how the government’s flip-flop has affected students. When the current semester began, she could hear them laughing during online classes. Now, there’s growing silence.

“The mental effects are definitely getting worse,” says Nakano. She has also noticed that some students who log in from Europe are now shutting off their cameras. “Prolonged online classes are taking a severe toll on many foreign students, especially those in countries with a big time difference.”

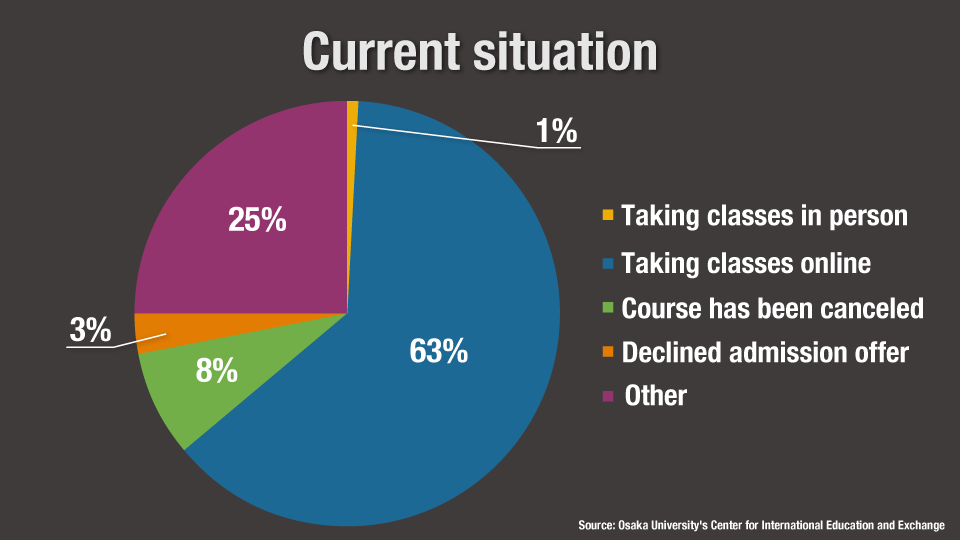

To get a better sense of the issue, Nakano conducted an online survey of current and prospective international students. A total of 644 people from 64 countries took part. Just 1 percent are taking in-person classes in Japan. More than 60 percent are studying online.

Getting closer to Japan

Hannah Davies has been attending online university lectures at her home in the United Kingdom from midnight until 7 a.m. each day. The strain soon became too much, prompting the 21-year-old to take action with three classmates.

In December, they moved to South Korea, where they will be able to live for up to three months. “We just thought it would be better for our mental health to go to a country where there's a similar time zone,” says Davies.

“The time difference was getting to us. It was making us lose our motivation to study. And now I think we all feel much better for it.”

If the third-year law student still can’t enter Japan when her South Korean visa expires, she plans to move to Thailand or another country in a similar time zone.

Davies says Japan’s rules “lack consistency” because Japanese citizens, free to travel between different countries, are not subject to the same restrictions as foreigners.

She adds that she appreciates the way nations like South Korea treat travelers equally despite much higher coronavirus case counts.

“It's sad to see that Japan won't adopt those same measures for students who are fully vaccinated and are willing to quarantine for that long when they expect other countries to accept their students.”

‘Support needed’

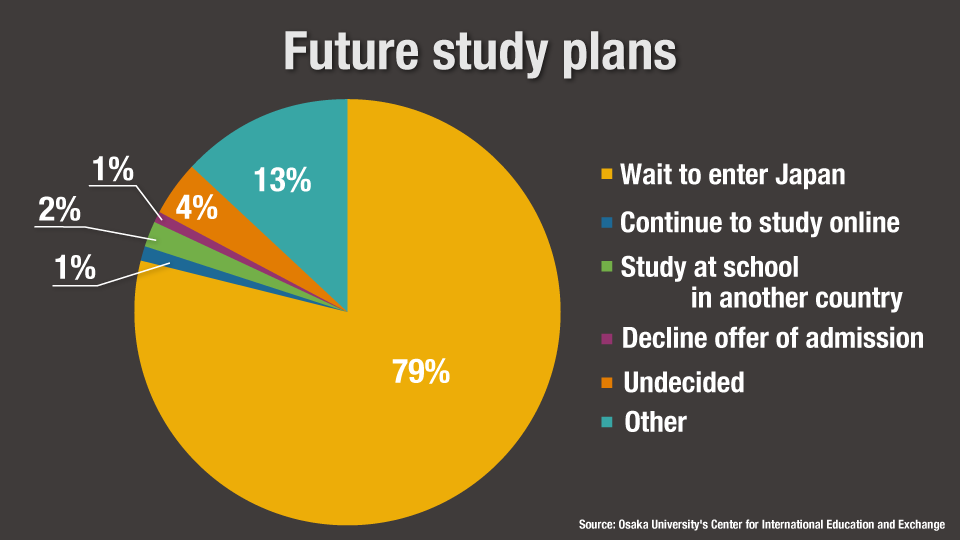

Despite the difficulties they’re facing, Nakano says most of the students she polled have no intention of giving up on studying in Japan. Nearly 80 percent said they will keep waiting, with only 2 percent indicating that they’ll study at institutions in another country.

Nakano is trying to raise awareness about their plight, which she warns “could lead to a terrible situation.”

“I have received about 600 messages in which students shared their hardships while taking online classes,” she says. “Many are reporting symptoms of depression. Some even mentioned suicidal thoughts.”

Some universities and language schools are already offering one-on-one counseling sessions or online events where international students can share their anxieties and learn to cope better.

There are also moves to provide recorded lectures to students who are stranded overseas, so that they can study at a more reasonable hour.

“Entering Japan would be the best solution for them. Everything else can only be described as a stopgap measure,” says Nakano. “At the same time, we professors, teachers and school staff should do all we can to not let our hopeful students down.”