“It was like, 15 people died today, 23 the next day and 30 more the day after,” says Ito Kyoko. The 82-year-old experienced the outbreak first-hand as a child on a boat repatriating people from Manchuria. “I thought I would soon be dead, too.”

More than six million Japanese nationals were heading home from abroad after Japan lost the War. Cholera, raging across Asia, spread fast on the packed boats—especially among people already in poor health.

Adults and children were told to remain on board when infections were first detected. As more people fell ill, they had to stay put for longer. Ito and her family couldn’t land for 40 days. When she finally stepped back on home soil, she did it without her younger brother.

He was three years old when he lost his life. Ito says she couldn't even grieve. “I thought I wouldn’t be able to survive with the heart of a human being,” she says. “The passengers were not treated like humans anyway—we were just part of the ship's freight.”

Conditions create breeding ground for illness

Footage apparently shot by members of the Allied Forces shows soldiers packed in ships moored offshore, the sick and healthy apparently not separated. Such conditions would only have fueled the spread of infections.

One surviving soldier wrote: “A man who had been in perfect health and was taking care of his colleague suddenly died after developing diarrhea, vomiting and other symptoms of cholera. Everybody was horrified at the fact that lives were being taken so easily and so suddenly. I might be the next.”

Kawahara Chiyo was among the Red Cross nurses in their teens and 20s who were dispatched to the ships. She is 94 now, but recalls the harrowing experience as if it were yesterday: “They had all lost so much weight, and were just skin and bone. I saw many die, one by one.”

Kawahara remembers soldiers carrying others on their backs to be transported to medical facilities in trucks. She says no drugs were available, and that there was no way to save their lives. Death came so soon that hospital rooms would be full one day, and empty the next.

True death toll not known

The US military designated the port-town of Uraga, Kanagawa Prefecture, as a major hub for accepting cholera-infested boats. A memorial near the site of a crematorium where the bodies were burned hints at the area’s tragic past.

Nakauchi Hiroshi, who has researched the repatriation program, says his father survived after being moored off Japan’s coast, adding that he would speak of his comrades who died. Nakauchi says at least 398 bodies were burned at the crematorium, but he believes the actual death toll to be much higher, taking into account the victims who are thought to have been buried at sea.

Post-war turmoil means we can never truly grasp the extent of the tragedy. “I can acutely sense just how much they wanted to survive and be reunited with their families,” he says. “It’s totally unacceptable that people who survived the war succumbed to an infectious disease while quarantined on ships so close to home.”

The measures Nakauchi refers to were set out by the US-led occupation forces at the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. GHQ determined that ships carrying Japanese returnees with just one cholera patient must quarantine for a full 14 days—more than twice the period required under an international treaty at the time.

“Putting up a barrier,” a GHQ official wrote in an order, “cholera should be stopped spreading into Japan’s mainland at all cost.”

Crawford F. Sams was in charge of Public Health and Welfare in occupied Japan. In his memoir, he writes: "If they had been allowed to move around Japan, they would have spread cholera everywhere in the country."

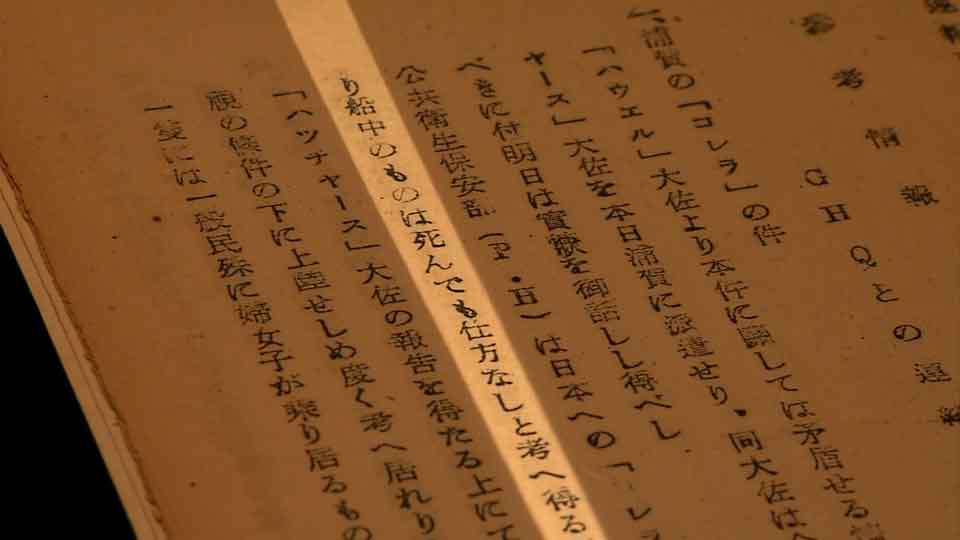

Japanese government documents show that Japan’s health officials were concerned about the situation in the ships.

"The quarantine policy was all about preventing cholera entering Japanese soil,” one wrote. “It seems like they thought it was inevitable that the people on board were dead.”

Nagasaki University Professor Yamamoto Taro is an expert on infectious diseases in tropical regions. He points out that quarantine measures are always set up to defend society, but often at the expense of those who need care. “When another new infectious disease emerges, with no vaccine or treatment, we should remember one thing: To always stand on the side of the people who are sick and isolated.”