Shinjuku Yotsuya 6th Elementary School is the closest school to the National Stadium in Tokyo. It had been preparing for the Games while the stadium was being built next door.

But because of the pandemic, everything was suddenly upended, and not everyone in Japan was happy about hosting the Games. I wanted to know what this experience would mean to the children.

I visited the sixth graders in July, just before the opening of the Olympic Games. Excitement was in the air as they saw dozens of different flags flying at the stadium from their classroom windows.

"Look, that must be the Peruvian flag!" said one student.

"No, that's Australia!" responded another. "The Peruvian flag has a mark in the center," a third explained.

Diverse curriculum

The construction of the National Stadium started in 2016, just when the students I met started off as first graders. With the Tokyo Games as the culmination, the school has been encouraging students to think about diversity in society and their role in it.

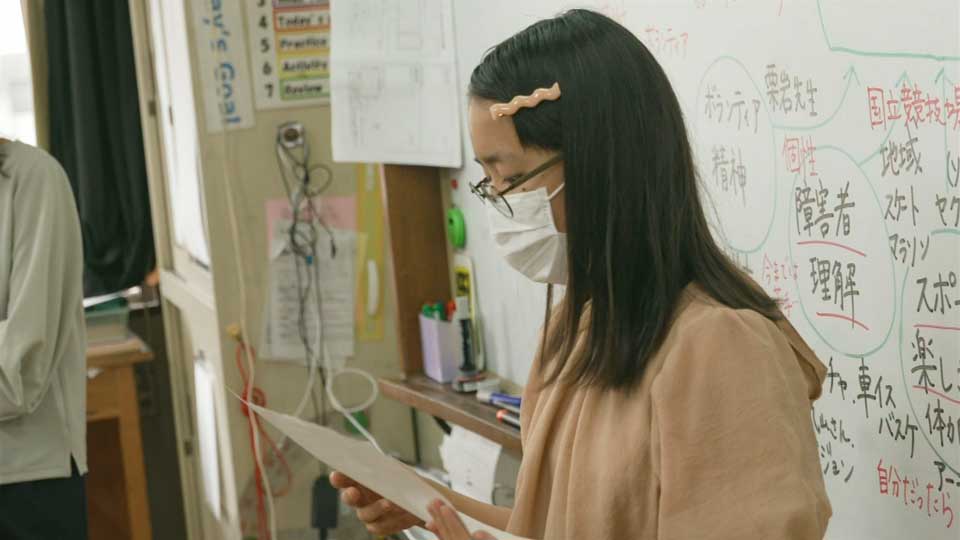

In Social Studies, they learned about different cultures around the world, as well as issues surrounding racism. They studied their own culture in Japanese class, and in English class they learned how to explain it in English. They were also given opportunities to meet people from other parts of the world and try out para sports.

So, for the students who have now become sixth graders, lessons on inclusiveness have always been a part of their school life. They spent 300 hours on these lessons, and it was all meant to lead up to the chance to watch the Paralympics in person.

But the pandemic had a huge impact. The decision on whether they would be able to watch the competition at the stadium was left until the last moment.

After a one-year postponement, the Games kicked off without spectators. Tokyo's new infection cases had risen to more than 5,000 per day just a week before the opening of the Paralympics.

The school had already decided to cancel other events, including a school trip in October. The children were obviously disappointed, but at the same time, they expected such a possibility. "I knew this would happen because infections were increasing," said one student. "I'm sad, but there's nothing I can do."

Decision day

The public was divided on the risks and benefits of taking kids to watch the Games. Olympic organizers left the decision on whether to participate in the school invitation program to municipalities.

Iwasawa Hajime, the principal of Shinjuku Yotsuya 6th Elementary School, said it's a tough choice to make. If they were only thinking of preventing infections, then obviously the best thing would be to cancel all events that carry any risk at all. But he pointed out that it's important to also think about what the children could learn through their experiences and what that would mean to them.

Just a week before the children were due to go to the National Stadium, officials finally told Yotsuya 6th Elementary School they would stick with the program. They believed the educational value outweighed the risks.

The school wasted no time in preparing a bulletin for the families of students. It decided to let them have the final say on whether their children would take part.

Sixth grader Rino showed her mother the consent form from the school as soon as she got home that day. When her mother asked about what she wanted to do, Rino said she wanted to go as she's been learning about the Olympics and Paralympics for a long time.

She also explained that the students would be sitting apart from each other at the venue.

Rino's mother was worried about COVID and thought carefully before checking "participating" on the consent form. She knew how much her daughter was looking forward to this opportunity, and the many things Rino had to give up over the previous 18 months due to the pandemic. So, she wanted to respect her daughter's wishes this time.

Rino said she wanted to see the Paralympics with her own eyes. "The Olympics and Paralympics are not only for those who are good at sports," she said. "The Paralympics offers a place for everyone to spread their wings without being discriminated against."

Split decision

The big day was approaching, and teachers were faced with another problem -- they were worried a divide would form between students who would attend and those who would not. Some have family members who are medical workers or have underlying conditions. They are especially sensitive to the risks of COVID.

Just two days before the program, the teachers held a meeting to discuss once again what students would gain from the experience. One said he wanted the children to feel the need to create an inclusive society. Another teacher believed that it would be a good opportunity to think about the importance of understanding others' situations.

Oka Chie, the vice principal of the school, pointed out that what's important is not whether they saw events in person or not. The important thing is that students make their own decisions. "If they decide to stay home, we need to ask what they learned at home and encourage them," she said.

The teachers decided to ask the students who would not go to the stadium to watch the Games on television and write an essay on their impressions to share in class.

Lessons learned

On September 3, 59 students out of the 69 in the sixth grade took part in the program. At the stadium, everyone wore masks and sat two seats apart from each other.

They watched the best para-athletes in the world performing and congratulating each other regardless of nationality. The children took it all in.

After returning to school, all the children got together and shared their feelings and impressions.

Here are how they expressed what the experience meant to them.

One student wrote: "All Paralympians have some kind of disability. I think they go through twice as much pain and hardship in their lives as we do. Their smiles and gestures were filled with the feeling that they overcame those painful experiences and were able to "beat themselves" as well as the feeling that they had fun and had done their best. One of the athletes once said they hate it when people feel sorry for them, and I felt I understood why."

Another said "I realized I'd been hesitant to interact with people with disabilities. But the athletes changed that. I learned not to see people as different from myself because of a disability or being of a different race, but to see the difference as what makes them unique, and to respect them. I learned that from the Paralympics."

One of the students who had decided not to go spoke of the sportsmanship they'd seen: "Something I noticed on TV was that medalists were going over to others who hadn't won a medal, hugging them and comforting them. I was surprised. I thought that was amazing."

Teachers spent six years exploring what the children would be able to learn from the Olympics and Paralympics. Their lessons aimed at raising awareness of diversity have broadened the students' horizons.

The pandemic may have created social divides, even over whether to take children to see the Games, but at this school, years of learning -- with the Games as the high point -- have helped shape a generation that accepts people with different values.