Introduction of ‘different dimension’ easing

Kuroda has overtaken Ichimada Hisato as the longest-serving head of the central bank. The 18th governor who served from 1946 to 1954, Ichimada, was so influential in the financial and business sectors that he was nicknamed “the Pope.”

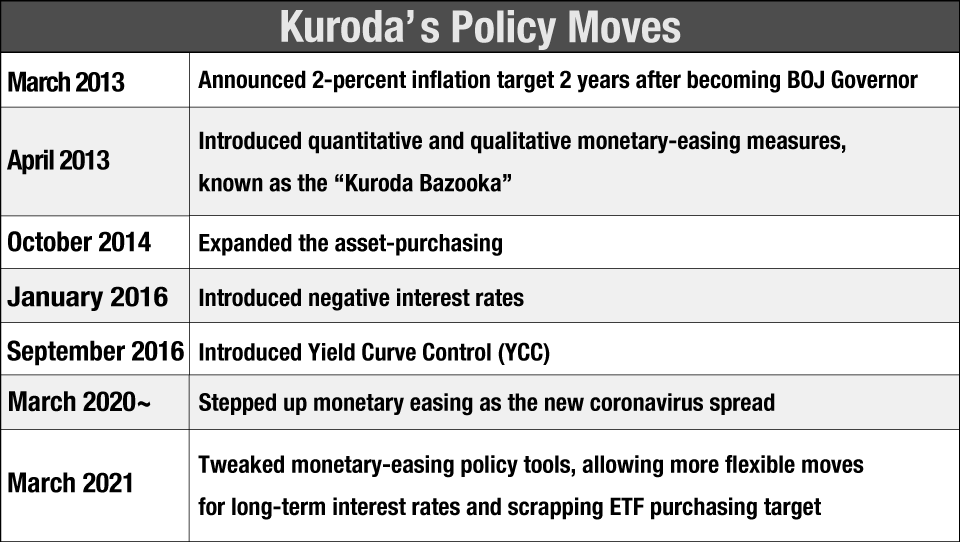

Kuroda is known for his aggressive stimulus program, called “the Kuroda Bazooka,” launched immediately after he assumed the BOJ’s top post. He unleashed a series of bold monetary measures on a scale that few central banks in developed countries have undertaken.

Traditional monetary measures involve raising or lowering policy interest rates. In April 2013, immediately after he took office, Kuroda launched an unconventional policy to make massive amounts of money available to the financial markets over a short period of time, mainly by buying government bonds and other assets even while the short-term benchmark interest rate was zero.

When Kuroda took the BOJ helm, Japan had fallen into deflation and was suffering an economic slump. Against this backdrop, the central bank announced a clear-cut target of achieving 2-percent inflation within roughly two years and vowed to do everything it could to reach the goal. This was aimed at directly affecting people’s expectations and flooding the economy with massive amounts of money. The bank hoped that the tactics would lift Japan out of deflation, achieve sustainable price rises and put the economy on a growth path. The program, different from those launched in the past both in terms of quality and quantity, came to be known as “monetary easing of a different dimension.”

In 2016, the BOJ introduced a negative interest-rate policy. In the first measure of its kind in the bank’s history, financial institutions are charged interest to keep cash in their BOJ accounts. It also introduced a policy of “yield curve control” to guide long-term bond yields to around 0 percent.

Despite all that, the inflation rate remained below 2 percent. The BOJ abandoned the timeframe for achieving the target in 2018, as Kuroda entered his second term. The bank’s massive monetary easing has thus become a protracted strategy.

In 2020, the BOJ raised the ceiling of its purchases of government bonds and other assets, in an attempt to further shore up the economy battered by the coronavirus pandemic. As Kuroda put it, the bank was “tenaciously” continuing its stimulus to hit the target, using various policy tools.

In its latest outlook released in July 2021, the BOJ projects the inflation rate to be 1 percent in fiscal 2023 -- when Kuroda’s tenure expires. There’s no sign the target will be achieved anytime soon.

Not that Kuroda has many regrets.

“I think that the monetary policy we have carried out was not a mistake,” he said after a BOJ meeting in September. “If we didn’t, Japan’s economic growth rate and inflation rate would have been lower, and employment would not have increased as much as it has.”

Experts’ views

Some experts agree with that assessment, others do not.

Nagahama Toshihiro, Senior Economist at Dai-ichi Life Research Institute, believes that Kuroda revived the Japanese economy. His stimulus measures went beyond the market’s expectations immediately after he assumed his post, while stemming excessive yen rises and stock declines, according to Nagahama.

A strong yen and low share prices had been weighing on the Japanese economy before Kuroda took the BOJ’s helm. USD/JPY was between 92 and 93 on foreign exchange markets and the Nikkei average was hovering a little above 11,600 as of March 1, 2013. Nagahama says that Kuroda turned the tables in one go with his “bazooka.” That, along with large-scale purchases of exchanged-traded funds (ETFs), consisting of stocks and bonds, attracted the world’s attention, drawing overseas investors, according to the economist.

Hayakawa Hideo, Senior Fellow at the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research, however, believes that Kuroda’s policies are distorting the market. “I rate him highly for boldly starting the large-scale monetary easing, but he had no Plan B in case he failed to achieve the 2-percent target,” he says. “He prepared only for a short-term battle, but ended up having to keep buying a tremendous amount of assets. The bank has distorted the market, which is a bigger worry.”

Negative effects of monetary easing

Experts have been expressing concerns about what they see are the negative effects of the BOJ’s prolonged monetary easing.

Assets held by the central bank have accumulated year after, amounting to 716 trillion yen, or over 6.4 trillion dollars, as of the end of June 2021. That’s over 130 percent of Japan’s GDP. The figure is far higher than the equivalent amounts at the Fed and the ECB. What’s especially noteworthy is that the BOJ held about 540 trillion yen, or about 4.8 trillion dollars, worth of Japanese government bonds, accounting for around 40 percent of that market.

This has enabled the Japanese government to issue bonds at lower interest rates, leading to concerns over a possible loss of fiscal discipline. There is also criticism that the market function of determining long-term interest rates is threatened by the central bank’s prolonged and large-scale purchases of government debt.

In another case of what the critics see as a market distortion, the BOJ held 7 percent of the total value of shares listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s first section as of the end of March 2021. These holdings of 51 trillion yen, or over 450 billion dollars, are in the form of ETFs.

There are concerns that the BOJ’s balance sheet is so inflated that it will be difficult for it to wind down its monetary easing without causing a big impact on the financial markets. Making a soft landing will be a crucial task for the bank.

The era of the “new normal” began during Kuroda’s tenure, necessitating monetary policy to adapt, according to Momma Kazuo, Executive Economist at Mizuho Research & Technologies, Ltd. “He achieved a certain level of success in getting Japan out of deflation,” Momma says. “But what has happened over the past eight years is proof that monetary easing has its limits, and it alone cannot raise inflation to 2 percent. It will be difficult to hit the target in five or even 10 years.”

Many financial institutions are suffering as a result Kuroda’s policies. Ultra-low interest rates have narrowed the spread on the institutions’ loans, and thereby their profits. Momma, who served as a BOJ Executive Director under Kuroda, notes that the bank went all out to achieve the inflation target from the start, but the focus of its policy in his second term has shifted to how to alleviate the negative impact. “Share prices and company earnings have risen, but for the economy to recover, wage hikes, which boost household income, are a must. The BOJ’s monetary policy alone cannot achieve it, so there should be a wide debate,” Momma says.

Remaining tenure

Kuroda’s second term ends in April 2023. It seems unlikely that the 2-percent target will be hit in the one and a half years until he leaves office. The governor says that there’s no point in talking about whether the target can be met during his remaining tenure. He claims the target is achievable, though that might not happen before fiscal 2024 and that the bank will “tenaciously” continue with monetary easing.

The US has laid out an exit strategy from its current round of monetary easing, which was introduced to deal with the coronavirus pandemic. The world appears to be entering a post-coronavirus economy. Monetary policy by the BOJ alone cannot put Japan’s economy on a full-fledged expansion path. For that to happen, the government and companies will also need to step in with wage hikes, improvements in labor productivity and other moves to achieve sustained growth.