"Please help me recover"

Wishma, a 33-year-old woman from Sri Lanka, died at an immigration facility in Nagoya on March 6. Support groups and affiliated doctors believe it was from starvation. "I saw her for the last time three days earlier," says Matsui Yasunori, an advisor at START, a support group for foreign detainees in Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture. "She was in a wheelchair. There was a bucket by her side in case she vomited. She had lost 20 kilograms in six months. Her lips were black, she was foaming at the mouth, and she couldn't move her arms or fingers."

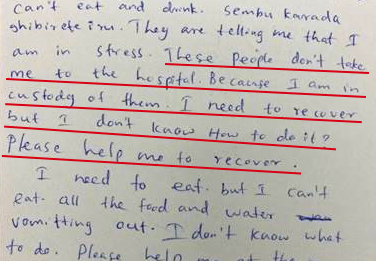

Matsui says Wishma had repeatedly requested medical care since January, when she started finding it difficult to eat. She wrote letters to a volunteer at START, stating her desire to receive appropriate treatment. "These people don't take me to the hospital because I am in custody of them. I need to recover but I don't know how to do it. Please help me to recover."

Wishma was eventually allowed to be examined at hospitals outside. She was given medicine, but did not receive treatments such as an intravenous drip, despite her and Matsui's repeated requests.

Matsui says that on February 16, immigration officials denied Wishma's request for provisional release to receive medical treatment.

Justice Minister Kamikawa Yoko has instructed the Immigration Services Agency to swiftly investigate the circumstances leading up to her death and release its findings as soon as possible. An intermediate report disclosed on April 9 was lacking crucial facts, such as how much she weighed at the time of her death, even though an autopsy had been completed.

Doctors on site but out of reach

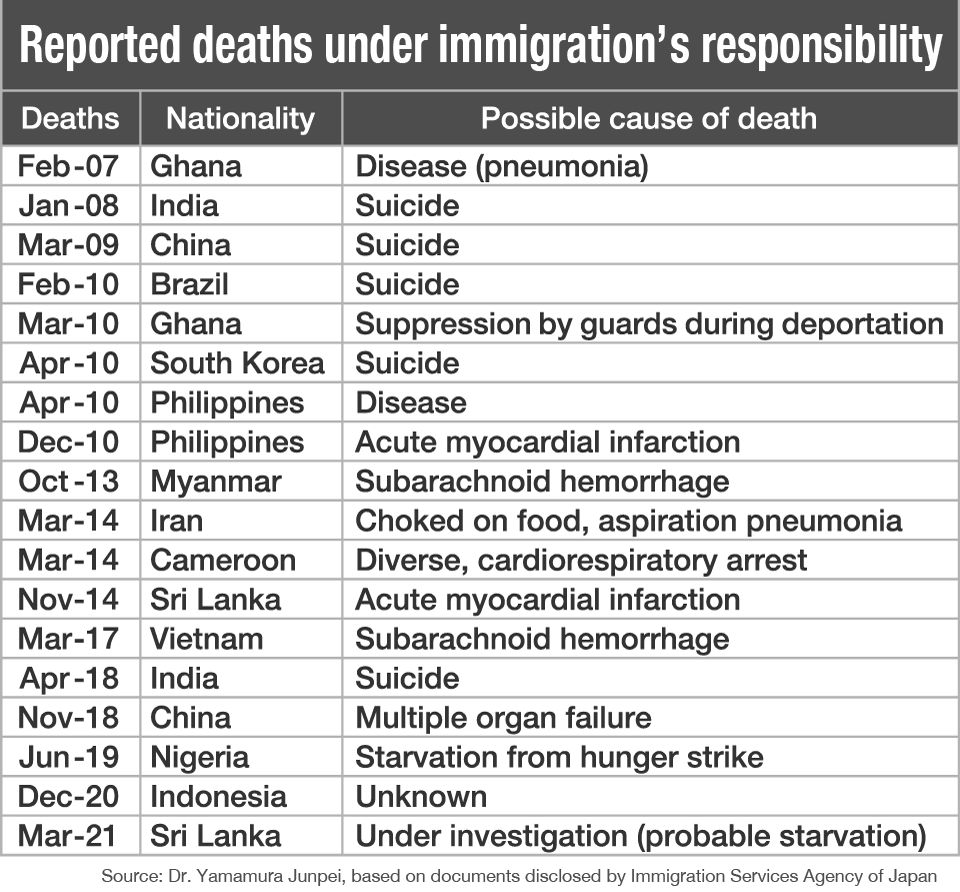

Wishma is the 18th person confirmed to have died under the responsibility of the Japanese Immigration Services Agency since 2007. Komai Chie and Ibusuki Shoichi, two lawyers who specialize in issues related to immigration, point out that the actual cause of death for many – Wishma included – may be the system itself at these facilities, which are not designed for long-term detention and are therefore ill-equipped for medical care.

Yamamura Junpei, a physician at the Minatomachi Medical Center in Yokoyama, shares that view. He says many of the almost 1,000 foreign detainees he has met over the past 19 years experienced all manner of ailments, including high blood pressure, fatigue, myocardial infarctions and depression, and did not have access to regular medical care.

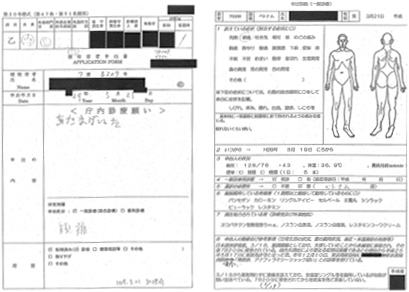

Detention facilities have a doctor on site, but the process for getting seen is far from fast. Detainees must fill out an application which they are given only if the official on duty at the time decides they should receive treatment. They then join a waiting list. A 2018 document provided by a major facility in Ibaraki Prefecture at the request of the Japanese Association for Refugees noted that it took an average of 14.4 days from application to consultation.

Quick-fix pills readily available

Doctor Yamamura is concerned about the heavy use of medicine at these facilities to compensate for the lack of proper care.

The frequent use of pills can have a lasting effect as many detainees are kept in these facilities for a long time. Deniz, a Kurdish man who spent a total of 5 years in detention, says he became addicted to sleeping pills, mood stabilizers and pain killers, sometimes taking 30 pills a day. He still struggles, even after being granted provisional release.

Yamamura also points out the danger of officials without medical expertise making decisions on how to provide prescription medicine such as Nitorol for detainees experiencing chest pains.

Officials distrustful of detainees

Medical treatment is one of the major reasons detainees can be granted provisional release, and that means officials are quick to doubt the severity of an ailment. A 2012 immigration report says, "many people request medical treatment just for malingering and minor illnesses."

A senior immigration officer who spoke on condition of anonymity says, "staff often do not take foreign detainees' medical complaints seriously, because they tend to think they are lying in the hope of being sent to an outside hospital, and freed." Yamamura says this can lead to wrong judgements with fatal consequences.

The problem was illustrated in court in 2019. Video footage was presented showing a Cameroonian detainee screaming "I am dying." He then rolls off the bed and stops moving. Guards come to see him, but he is given no emergency medical assistance. The following morning, he was taken to a hospital, where he was confirmed dead. The man was diabetic, and had been complaining about pain in his legs. His blood sugar level was nine times higher than normal at the time of death. In the ensuing lawsuit, the Immigration Bureau said it was following protocol by monitoring the man through the camera.

Emotional distress for medical staff

The situation can also be stressful for the medical professionals who work at Japan's immigration facilities. A psychiatrist who examined a Kurdish man, Colak Memeth, hinted at his frustrations in a February 2019 report: "I told him the environment here is very harsh, but I am unable to do anything about it."

Memeth was detained for 20 months. In March 2019, he went into convulsions and started foaming at the mouth until losing consciousness. But he was not immediately sent to a hospital. Ambulances arrived at the detention facility at the request of his brothers, but were turned away. Memeth was finally hospitalized the following day and released three months later.

Memeth's case is one of many in which doctors are prevented from building relationships with the detainees who need them. Yamamura explains that medical professionals often become resigned to the futility of the system, and quit. What's more, the Immigration Agency has found it difficult to secure dedicated doctors.

Law revision poses questions

The Japanese government plans to reform the immigration law in an attempt to limit the growing number of foreigners in long-term detention. A draft revision is up for discussion in the Diet this month, but it says little about medical care. Immigration lawyers and members of the opposition want the discussion to put on hold until the investigation into Wishma's death is concluded.

Doctor Yamamura says senior immigration officials often tell him that their work is "to detain and deport illegal foreigners. Deciding whether someone can endure detention or not is a role for doctors." But Yamamura says the government must take overall responsibility for detained foreigners in every respect, including health.

Yamamura says it's time for a serious discussion about how foreigners are treated. "The issue goes beyond improving medical care. We need to look deep into the cause of the problem, and into the root of society, regarding the way we view foreigners. They are not a disposable labor force, but human beings."