At a Tokyo event called the "Kokujin Experiences" last month, about 250 people turned out in person and online to discuss what it's like to be Black in Japan. Mask-wearing spectators lined the stairs, as people shared their experiences as a kokujin, the Japanese word for Black people.

"The image of Black success has always been sports and entertainment," said Warren Stanislaus, a British African panelist. When he moved to Japan about 15 years ago, he said people commonly told him he looked like Eddie Murphy and Michael Jackson.

The comment sparked laughter, while allowing people to reflect on their own personal bias. Society's appreciation of Black people, he said, relies on the physical not the intellectual. "Racism is there and sometimes it can be subtle," said Bongekile Motsa, another panelist who is a Swati student at a Japanese college. "It can be confusing whether what you are facing is racism or it's just people being ignorant."

Jaspora, one of the country's largest African diaspora communities, organized the event to open minds. Once the two-hour session wrapped up, the group seemed a step closer to reaching that goal. "It's really important to hear what they experienced and felt," said one young Japanese woman after the event, adding that hearing directly from Black people can be an eye-opening experience.

Sena and Pele Voncujovi helped found Jaspora. Their father is from Ghana, and their mother is Japanese. They were born in Tokyo, but moved to Ghana when elder brother Sena was two years old. A main reason was the possibility they would face discrimination being Black. "My father thought it would be better for us to be raised in Ghana because wherever we go, we are going to be considered Black," Sena said. After more than 10 years in that country, they moved to the United States for school, before settling back in Japan.

Living in their birth country hasn't always been easy. They speak Japanese fluently and understand its culture, but sometimes are treated as outsiders, even by friends. The brothers say people don't always recognize that their preconceptions about Black people are a form of racism. "I guess because I had dreadlocks, my neighbor thought I was a drug dealer," Pele said, recounting how a friend once described him as "sketchy." "It was always in a joking manner, but I realized it takes time to break the stereotype away."

A massive and global movement is starting to change that. The killing of George Floyd by American police fueled a wave of protests, under the rallying cry, Black Lives Matter.

Protests were held in Tokyo as well, and Sena and Pele took part to bring attention to discrimination here in Japan. They say having so many black people take to the streets made a powerful statement. "The BLM movement made some people question their own personal racism and how they see the world. I hope that question would inspire them to learn," Pele said.

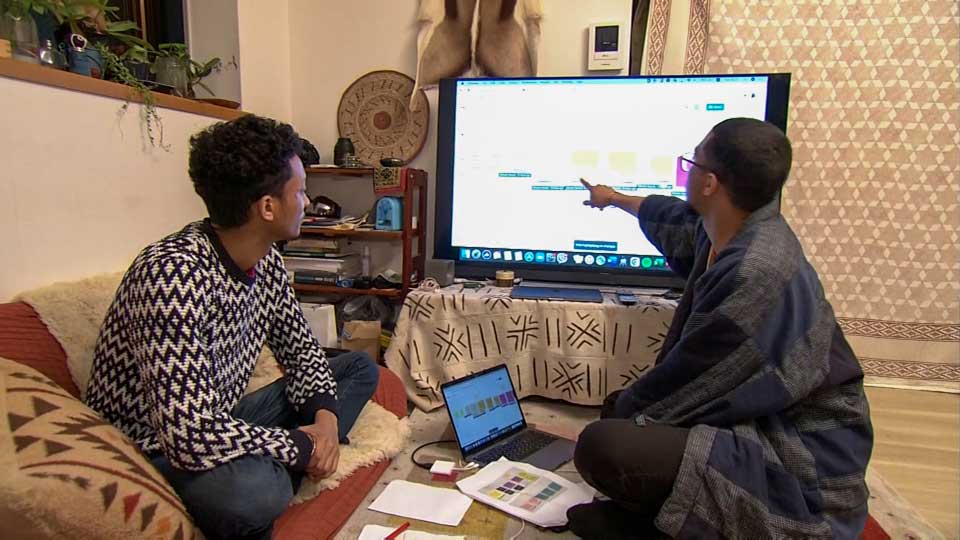

From there, the brothers hope young Japanese people will be able to take on some of the work to eliminate discrimination. They're working on a program for Japanese high school and college students which will allow them to teach their peers about diversity. Sena's belief in power of education comes from his personal experience.

During adolescence, the two brothers spent six months at a local Japanese school where they remember children shouting "foreigner" and "African" in the hallways. "When you don't know and you don't engage with [Black people], you don't see them as people that are just like you, then it's easier for you to just dismiss their struggles," Sena said. But as the kids learned about Ghanaian culture, that ignorance began to subside and friendships blossomed. "I think Japan really needs more of that open-mindedness to thrive."