During December 2020 and January 2021, NHK sent more than 4,000 questionnaires to residents from disaster-stricken areas in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures. It received 1,805 responses.

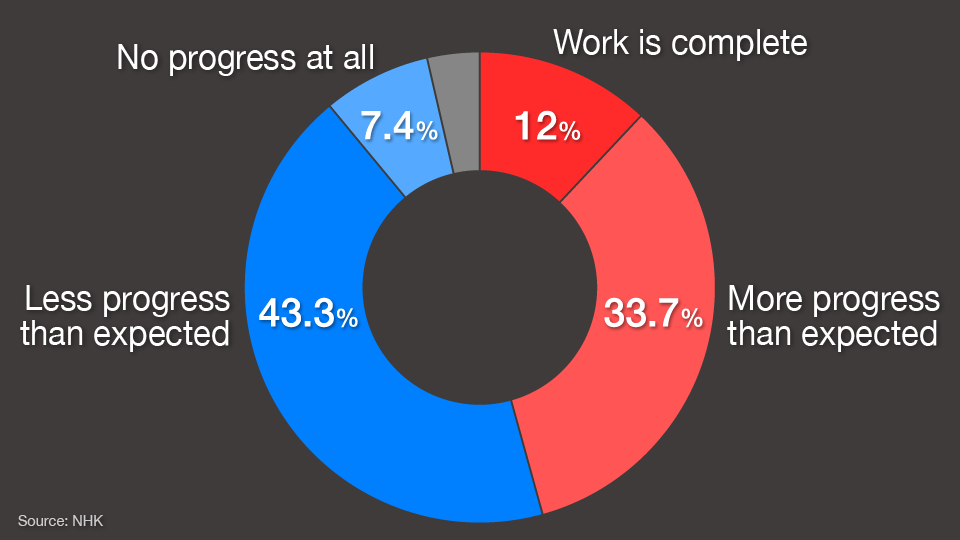

On the reconstruction status of where the respondents lived at the time of the disaster, 50.7% had a negative view, which was five points higher than the number of satisfied responses.

Furudate Shozo, 85, from Miyako City in Iwate Prefecture, wrote in the survey that reconstruction is complete. But he says this doesn't mean he's satisfied, even though he has been involved in rebuilding efforts as chairman of a local neighborhood association. He describes the situation as worse than he expected.

Furudate's house and shop were swept away by the tsunami. Construction work was done to raise the land in Kuwagasaki District and new homes began popping up six years ago. In a survey carried out six years after the disaster, Furudate said he was happy to see private houses being built.

But his outlook changed as it became apparent that the number of residents returning to town was much less than anticipated. In a survey carried out eight years after the disaster, he expressed doubts about progress – and one year after that he wrote that he felt a sense of emptiness despite working so hard to rebuild the community.

Even now, only half of his district's population has returned. There are vacant lots everywhere. Last year, Furudate was forced to close the shop that he had rebuilt.

"Since I was expecting people to return, it was a major disappointment when they didn't," he says. "The major issue from now, is how to restore vitality to the community. Even a decade after the disaster, we are far from recovery."

Soaring rent for disaster housing

Many people who lost their homes have resettled in public housing built especially for disaster victims. Japan's government has constructed enough facilities for 30,000 households.

But residents are struggling to pay bills. While the disaster residences offer low rent when people initially move in, a tiered cost structure sees rents rise in step with the amount of time spent there. Rents are also hiked if residents' salaries increase.

One year after the disaster, Sugiyama Ayumu from Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture, moved into a disaster housing complex with her family. In addition to her husband, that now includes three children aged 10, 7 and 3 years old. When she moved in, the rent was about $80 a month, but it has since shot up to more than $370. Sugiyama is making ends meet by cutting back on groceries. But she worries that food expenses will grow as her children get older.

"Other families around the same generation as us have been forced to move out of this disaster housing because of the high rent," says Sugiyama. "Disaster housing was built for people who can't rebuild their homes, but it seems like that's only a consideration when people first move in."

The NHK survey found that nearly 40% of disaster housing tenants reported that their rent has increased. For just over 10%, it had more than doubled. Almost three quarters said they are cutting back on living expenses, and nearly 40% are dipping into savings to pay rent.

Kimura Reo, a professor at the University of Hyogo, warns that the rising rent has a broad impact: "If a generation of people in the prime of their lives move out of disaster public housing, it will have a negative effect on sustainable community development. Taking this into consideration, the disaster public housing model and rent subsidies must be reexamined."

A key concern for people in the disaster-hit areas is that concern and support for their situation is fading over time. The NHK survey found that half of the respondents themselves had waning interest in reconstruction. Most people - 69.1% – believe human and economic assistance is set to fall away.

Some of the problems are being addressed in the government's new five-year reconstruction plan. It provides for mental health care, support for local communities, and assistance for residents to return to areas where evacuation orders have been lifted.