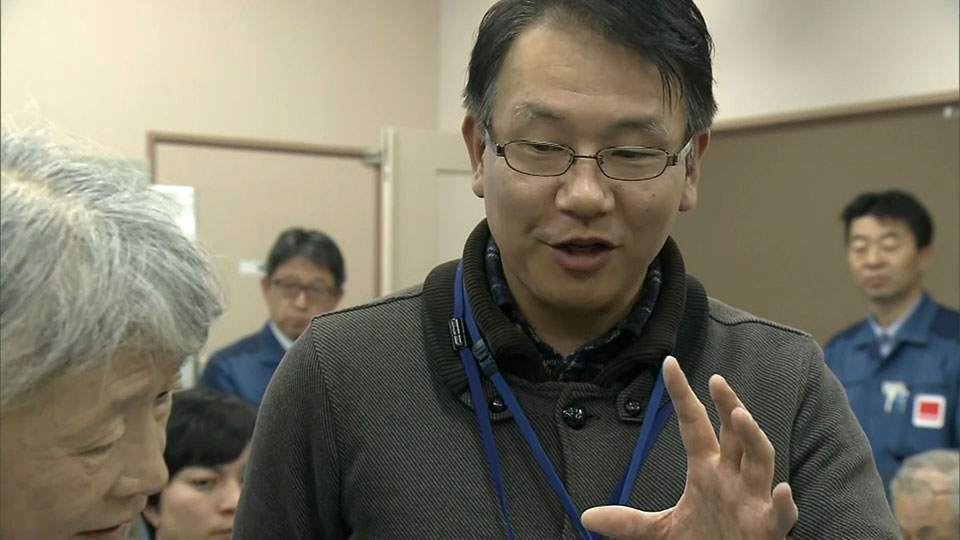

“Before the disaster, I explained to residents that an accident like Chernobyl would not occur in Japan. But it actually did, and that stunned me,” he says. Kino says he had bought into what he now calls a “safety myth”.

The triple meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant that followed the 2011 earthquake and tsunami “was a very shocking event for me as an expert”, reflects Kino. He feels a personal sense of responsibility to help the people affected, and is now in charge of the next step for the crippled plant.

“I’m dedicating my life’s work to the decommissioning of the nuclear reactors in Fukushima,” says Kino.

Confrontation and conciliation

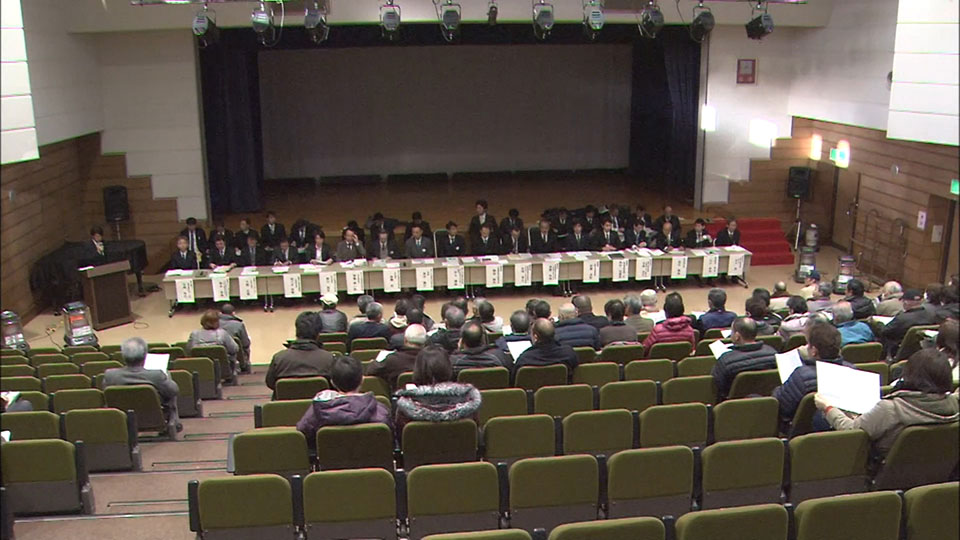

Immediately after the disaster, Kino was dispatched to Fukushima. He attended countless meetings with local residents, many of whom had to abandon their homes and livelihoods. Some were even prevented from entering areas to search for missing loved ones.

“Many of the residents were annoyed that government officials like me would come to Fukushima for an hour or two, then return to Tokyo. They told me I needed to live in Fukushima to really understand their situation,” he says.

Kino began to spend more time with the people hit by the disaster, even when he was off duty. He accepted invitations to local events, including rice planting and harvests, and local festivals. His sphere of acquaintances began to grow, and he decided he needed to move to the region.

Becoming part of the community

As he became part of the community, Kino felt the hostility diminish. One resident he has close dealings with is Kimura Norio. Kimura lost his father, wife and daughter in the tsunami. His house is located in a contaminated no-entry zone.

The area where Kimura’s house is situated has been earmarked as a potential site for the temporary storage of contaminated soil. But Kimura refuses to sell his land. Moreover, he wants the government to leave the area’s cultural facilities, including school buildings, shrines and temples, alone. He also wants his house to remain as is.

“The people who lived there before the disaster have almost given up on their houses and land, so I’m worried the culture and nature will disappear,” says Kimura. “I don’t want the area’s history to be forgotten.”

Kino supports the concept. “I hope his house, and facilities such as schools that were hit by the tsunami, will remain. Leaving them as they are tells a story.”

The way forward

Kino’s most pressing challenge now is what to do with the contaminated water that is being stored at the plant. A government panel of experts released a report last year suggesting the most practical solution is to release it into the sea or atmosphere – as long as the water meets a specified concentration limit for the tritium isotope. Fishermen and others remain strongly opposed.

Kino outlined the problem in a speech to high school students in Fukushima late last year. He explained that the Fukushima Daiichi compound is running out of space for water storage, describing it as an issue that must be resolved urgently.

“There is a possibility to increase the number of water tanks at the plant. But that just postpones the problem,” he told the students. “The plant has a finite amount of space.”

Kino believes it’s his duty to be as open and transparent as possible with the local people because the decommissioning process is likely to be difficult.

“I think there is no choice but to continue dialogue with everyone. I don’t know if they understand or agree with our measures, but I have to meet, talk, and start the conversation.”

For the next generation

Kino takes young government officials to Kimura to listen to his story. Kimura says he was surprised by that at first, because he is such a vocal critic of nuclear power and the government.

“From Kino’s standpoint I thought it was a little strange,” says Kimura. “But I’m grateful for his work. Thanks to him, I can share the truth about what happened here with young bureaucrats who will be responsible for the country's future.”

Kino says that’s exactly why he does it: “We need to pass on what happened here. It’s especially important for young people who can use the knowledge for the whole of their careers.”

Kino is 52 years old now, but he doesn’t want to stop working for Fukushima.

Each year, he writes to the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry to let them know he wants to stay in his post.

“As someone who has studied nuclear power, I have a responsibility to Fukushima. I don’t know how much I can do, but I know I want to do my best to decommission the plant and rebuild the prefecture,” he says.