A state of emergency is now in place for 11 prefectures, including Tokyo and Osaka. But as it stands, Japanese law does not allow for the imposition of penalties related to the pandemic. This is partly because the country's Constitution upholds people’s freedom of movement.

But Health Ministry officials proposed legal amendments to get around this at a meeting on January 15. They cited growing reports from local health centers about an increasing number of asymptomatic people who refuse to isolate at home despite having tested positive.

Health Minister Tamura Norihisa wants to ensure there is a legal basis to order infected people to self-isolate in designated facilities, or be hospitalized. Criminal penalties are being considered for those who refuse, including a prison term of less than one year, or a fine of about one million yen, or about $10,000.

"The plan restricts people's rights," Tamura says. "But we can't fully deal with the situation unless we have stronger legal powers."

The government plans to introduce bills that allow for the new measures to the current Diet session that began this week.

NHK Polls

NHK polled 3,600 people in November and December about changes to the government's coronavirus policy.

Asked if it was acceptable to restrict individual freedom as an infection control measure, 87% said they support or somewhat support the idea.

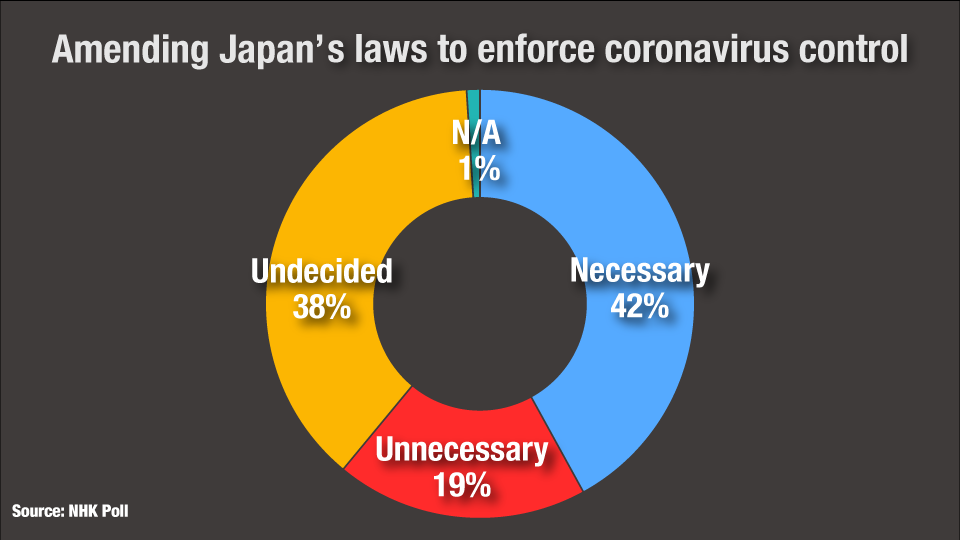

But people are divided over compulsory measures enforceable by amended law. 42% said that was necessary, 19% said it was unnecessary, while 38% were undecided.

Experts call for cautious debate

"Any law that restricts individual freedom should come with a mechanism designed to prevent abuse of power,” warns Japanese Constitution expert, Kyoto University Professor Sogabe Masahiro. "Japan needs a system to check the government, such as a human rights panel, or an ombudsman group."

One member of a government panel advising on the pandemic, Kawasaki City Institute for Public Health chief Okabe Nobuhiko, is also cautious.

"We must remember that the law will stay in effect long after the outbreak ends, and could be brought back in case of another outbreak," Okabe says. "We should not make a rushed decision. It’s worth considering a way to make a temporary law."