“It’s important to preserve their accounts with accurate English,” says Umayahara Rumi, a high school senior at Eishin Gakuen in Fukuyama City, Hiroshima Prefecture. “But at the same time, we want their words to be accessible to younger generations, so we have to use precise but simple language.”

Rumi belongs to the human rights club at Eishin Gakuen. The group does a range of humanitarian work, including aid projects for natural disasters. It also collects signatures in support of nuclear abolition. Recently, it has been devoted to translating hibakusha testimony.

The project started in the spring of 2016, when some members of the club noticed there was a lack of published material about the life of one of the most prominent hibakusha—Tsuboi Sunao. The club had met him during their activities to promote peace.

The students decided to take matters into their own hands and conducted a series of interviews with Tsuboi in an effort to document his life, starting on the tragic day in August 1945, and following his career after the war.

Tsuboi was a 20-year-old university student when the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. As a math teacher after the war, he made it a point to tell students about his experiences. He even introduced himself as “Pikadon sensei,” a nickname that references the flash and boom of the atomic bomb. Later in life, he remained committed to the hibakusha cause and in 2004 became the chairman of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations. He has held the position ever since and met with US President Barack Obama in May 2016.

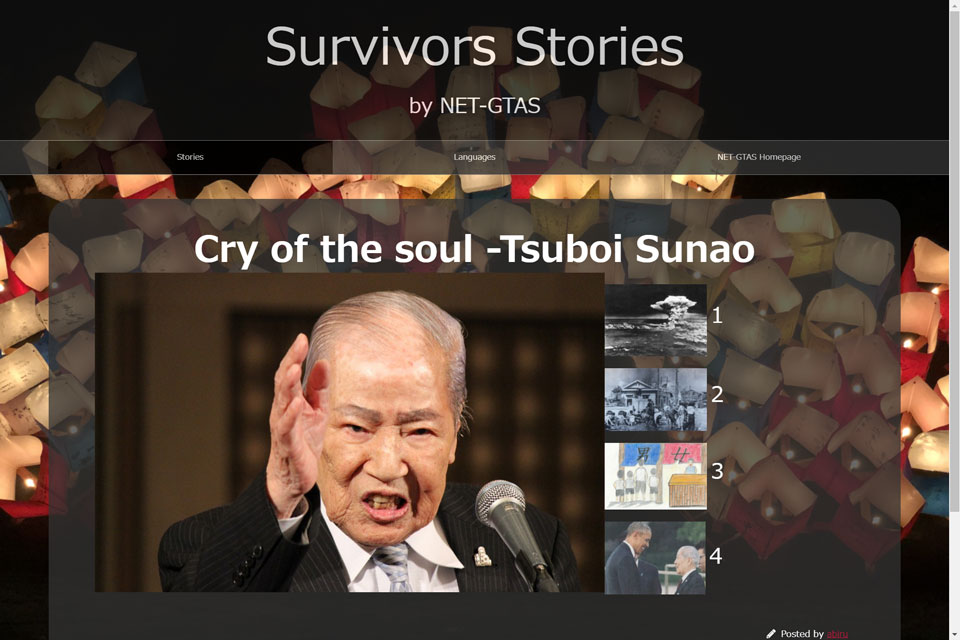

In 2017, the members of the Eishin human rights club compiled their interviews with him into a booklet titled, “Cry of the Soul: Tsuboi Sunao.” A copy was donated to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

But the students weren’t done. They wanted to give people around the world the chance to read the interviews, so they launched a project to produce an English translation, in cooperation with the Network of Translators for the Globalization of the Testimonies of Atomic Bomb Survivors, or NET-GTAS. The group, made up mainly of professors at the Kyoto University of Foreign Studies, gave the students advice on English expressions and terminology. After over a year of hard work, the English edition of the booklet was released online in December of 2019.

“The voices of the hibakusha have been the driving force of the nuclear disarmament campaign,” says Rumi. “Their number is dwindling so every second counts. We have to spread their experiences across the world as soon as possible, while they’re still with us. And as a Hiroshima native, I feel like it’s my duty to do so.”

The human rights club has already started on its next project, an English translation of the story of Kiriake Chieko, who experienced the Hiroshima bombing when she was just 15 years old. The club had previously conducted a series of Japanese interviews with her, which included a harrowing account of how she treated the burn wounds of her junior high school classmates with tempura oil.

“When I’m translating her words, I always picture the expressions she made when she was speaking to us,” says Sakami Tomoka, the club president. “Her eyes were full of tears, her voice quivered, and she clenched her fists tightly.”

The club discusses the particulars of expression at meetings, debating which English terms most accurately convey the nuances of the testimony. And when there is something they cannot agree on, they contact NET-GTAS for help.

But sometimes they encounter phrases they have trouble grasping the meaning of even in Japanese. When that happens, they speak with Kiriake directly and ask her for help.

“For example, the school system now is completely different from the one 75 years ago,” says Tomoka. “Differences like this make it hard to accurately convey the atmosphere of Japan at the time. But we're trying our best.”

Nobu Kazutoshi, the president of Eishin Gakuen and the former staff supervisor of the human rights club, says the translation work is worthwhile on its own, but that it is made particularly important by the fact that young students are doing it.

“The translations could be done easily by government officials or professionals,” he says, “but I think the fact that it is being done by students who are doing their best to understand the feelings of the hibakusha makes it more meaningful. And hopefully, it can touch other young people around the world.”