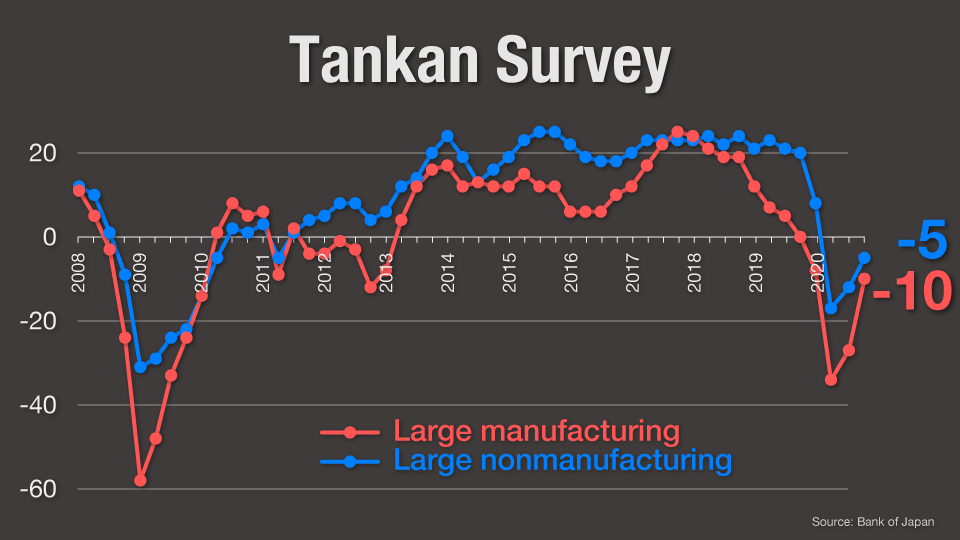

When the Bank of Japan's Tankan survey was released earlier this week, it painted a seemingly rosy economic picture. Business sentiment had picked up over the past three months, with both large manufacturers and non-manufacturers citing an improved mood despite the coronavirus pandemic. But any optimism engendered by the report was short-lived. Later that same day, the government announced it would be halting its domestic travel campaign for the year-end holiday season. Policymakers are now scrambling to find alternative measures to boost the economy and help those most in need.

The latest Tankan survey shows that a wide range of companies seemed to experience the benefits of recovery during the September to November period. Business sentiment among large manufacturers improved from -27 to -10 during those three months. The mood also ticked up among non-manufacturers, rising from -12 to -5. Analysts say this is largely due to an increase in customers to restaurants and hotels, driven by the Go To Travel campaign.

But this month, the mood has already darkened. Both big and small non-manufacturers say they expect the economy to worsen in the coming months. They cite a higher yen, reduced salaries and year-end bonuses, and slower exports – all due to the pandemic – as factors that will put an end to the economy's short-lived recovery.

For now, the labor market has been holding firm, with the jobless rate steady at slightly over 3%. But experts say underneath this figure lies a serious problem in the form of "economic bipolarization." According to Tokyo Shoko Research, the pandemic is taking a much greater toll on small- to mid-sized companies than large corporations, with 8.6% of such firms apparently close to going out of business. Nearly half say that's a possibility within one year. If all these businesses fail, this could lead to the loss of a staggering 1.2 million jobs.

The effects of "bipolarization" are also being felt at the worker level, with the pandemic widening a gap between regular and non-regular employees. According to a Labor ministry survey, the number of regular employees increased slightly over the past five months compared to the the same period last year. Meanwhile, the number of non-regular employees has decreased for the past eight months. This has led to a decline in opportunities for junior high and high school graduates. Another survey found that job openings typically filled by these recent graduates are down 20% from last year.

For its part, the government has recently implemented two measures to tackle this bipolarization. One aims to encourage companies to share employees. For example, a sightseeing bus driver out of work due to the pandemic could temporarily transfer to a delivery services company without quitting his job.

The other policy involves providing subsidies to companies that hire workers with no experience, which the government hopes will create more opportunities for recent graduates. But some experts have questioned the efficacy of this measure, saying it is unlikely that subsidies will be enough to convince struggling companies to hire workers they will have to train.

One idea that has been floated as an alternative is for the national and local governments to hire new graduates themselves. Such a program would both help the country at a time of exceptional demand for public services, and contribute to building new careers.

Experts also say the current crisis has made it clear the government needs to update its job seeker support system. The criteria to qualify for the current program are so strict that very few people have actually been able to use it. The current economic malaise makes the need for a functioning support system even more pressing.

Despite the start of vaccinations in the UK and the US, the pandemic is far from over. There is still time for the government to step up for people who are in desperate need of a helping hand.