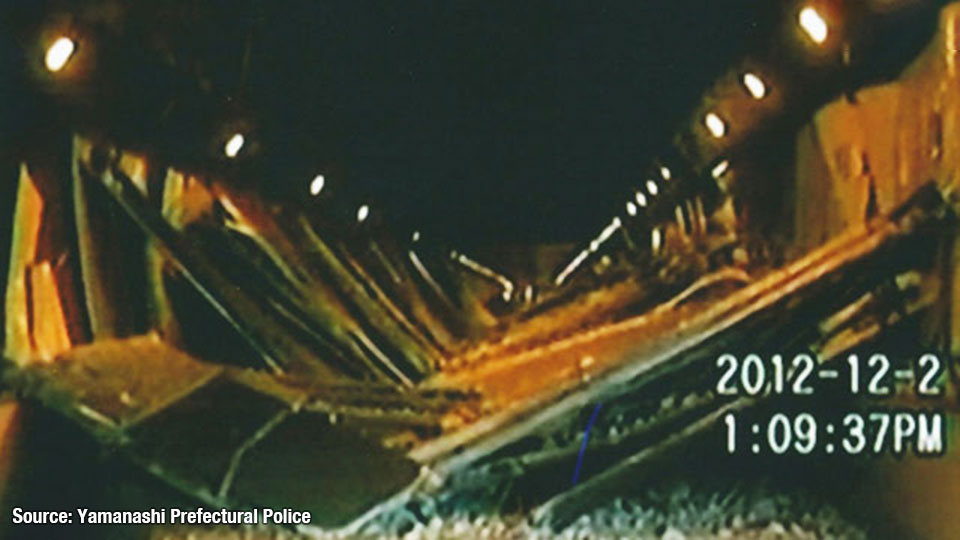

In 2012, nine people died when a 140-meter section of the Sasago Tunnel’s concrete ceiling fell off in Yamanashi Prefecture, west of Tokyo. A report pointed to inadequate inspections. The tunnel, almost five kilometers long, opened in 1977 along the Chuo Expressway.

The government panel set up to investigate warned that Japan needs to focus on maintaining infrastructure to avoid fatal disasters such as a bridge collapse. It urged the central and local governments to prioritize maintenance ahead of new construction.

To keep, or scrap?

In the post-war years, Japan pressed ahead with infrastructure projects to support a growing population. Decades later, many structures need repairs or full renovation.

Officials in Toyama Prefecture, on the Sea of Japan coast, are struggling with a budget shortfall for bridge maintenance. More than 200 need attention in the city of Toyama alone. Only about a third are getting fixed.

The city planned to start more repair work this year with an investment of ¥2 billion, or about US $19 million dollars. But it only managed to secure about ¥1.4 billion through municipal funds and state subsidies.

Toyama is one of many municipalities in Japan with an aging and shrinking population. The city’s is expected to contract by 18.1 percent through 2055, according to the National Institute of Population and Social Security. By the same year, city planners estimate maintenance work for the 2,200 bridges they oversee will cost a whopping ¥25 billion per year, or about US $240 million.

“We believe it’s impossible to keep all of the bridges,” says Toyama mayor Mori Masashi. “It’s vital to convince residents that we must do away with the conventional thinking that people should receive the same level of administrative services no matter where they live.”

Natural disasters impose an extra burden on local governments. Okitsuru Bridge in Kumamoto Prefecture was swept away during torrential rains in July this year. Because it was so important for residents of the village of Kuma, four years ago the local municipality spent Y40 million on waterproofing work for the bridge. That’s all gone to waste.

“It can't be helped because of a disaster,“ says Kuma village official. “But it is painful.” He remains worried about another disaster if and when the bridge gets replaced.

According to an NHK survey of 130 municipalities, more than one third say they are behind with bridge and road maintenance work.

Many cite budget problems and say they have too many structures to maintain. About 80 percent said they are considering tearing down some of the infrastructure they manage.

Nagai Kohei is an associate professor at the University of Tokyo, and an expert on infrastructure maintenance. He says local officials need to win public understanding as they decide what to keep and what to bulldoze.

“When identifying priorities, the exact conditions of aging bridges and roads should not be the only factor,” says Nagai. “The possible impact on residents’ daily lives, such as traffic volume and the distance of the detours they would have to make, should also be considered.”