The Ainu Measures Promotion Act, which came into force last year, is the first legal recognition of the Ainu as an indigenous people from the northern part of the Japanese archipelago, mainly Hokkaido.

The Ainu boast a unique culture and language. Until the 19th century, their main activities were hunting, fishing, gathering plants and farming. They also actively engaged with surrounding regions through trade and other forms of exchange.

During the Meiji Era in the 19th century, assimilation policies threatened the Ainu way of life. More wajin, or ethnic Japanese, were sent to promote changes overseen by the Hokkaido Development Commission, established by the government. It banned many Ainu traditions including salmon catching, hunting with poison-laced arrows, and tattoos for adult women. After the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act was enacted in 1899, Ainu school students were urged to learn Japanese. Today, UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger lists Ainu language as “critically endangered”.

A place to share and learn

Upopoy is the Ainu term for “singing in a large group”. The new complex also features a traditional village, or kotan, and a memorial facility to honor the deceased.

The National Ainu Museum is one of Upopoy’s core facilities. It has about 10,000 items, including tools that the Ainu used in their daily lives. The displays are divided into six sections, each with different themes such as history and language. Visitors can also watch films to learn more about Ainu culture.

The museum director is cultural anthropologist Sasaki Shiro. In an interview with NHK, he said: “Greater importance is being attached to Ainu culture. It may suggest Japan has become aware that without the promotion of cultural diversity, it could be at risk.”

Optimism grows among young Ainu

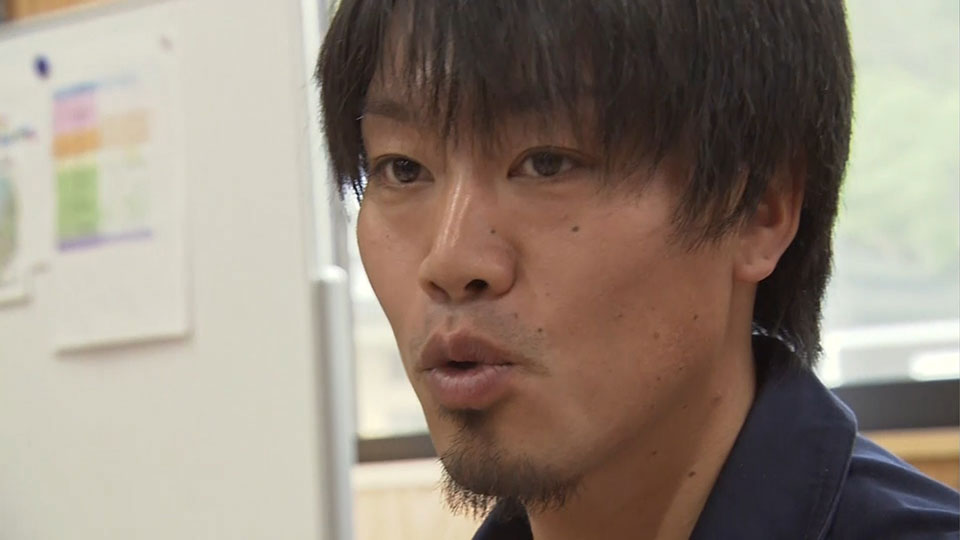

Yamamichi Yomaru is an Ainu who works at Upopoy. The 31-year-old was raised in the town of Biratori’s Nibutani district -- one of the few areas where Ainu culture remains active. For three years from 2011, he studied the Ainu language and learned traditional craft skills. He now demonstrates wood carvings and shares his knowhow in a hands-on program.

Yamamichi is pleased by the growing interest in Ainu culture. But he says many people mistakenly believe that the Ainu still hunt, and live in traditional dwellings with thatched roofs. For him, it’s all about developing a better understanding: “We want visitors to realize that Ainu life is no different from theirs, and that we’re trying to preserve our culture, with pride in our roots.”

Criticism on how history is portrayed

Some people have concerns about how Upopoy portrays the treatment of Ainu people. Emori Susumu, a professor emeritus at Tohoku Gakuin University in Miyagi Prefecture and an expert on Ainu history, says the museum will spur people’s interest, but doesn’t adequately explain the government’s past policy to assimilate the Ainu.

Emori says there are Ainu people who still hide their identity, out of fear they might become subject to discrimination or prejudice. “The exhibits alone may not help visitors fully understand why modern Ainu people are unable to speak their language, and why their traditions vanished,” he counters.

A facility led by its people

A spokesperson says the facility is designed to feature the Ainu as the main players, instead of disadvantaged people. All the displays, from the planning stage, reflect the views of Ainu people. The language is the first used as guidance and information. But many management staff are waijin sent from the central government, including museum director Sasaki.

Sasaki says: “Upopoy is designed to attract various people from around the world to deepen their understanding about Ainu culture,” adding he wants to entrust the Ainu people to determine how Upopoy is operated and managed in the future.