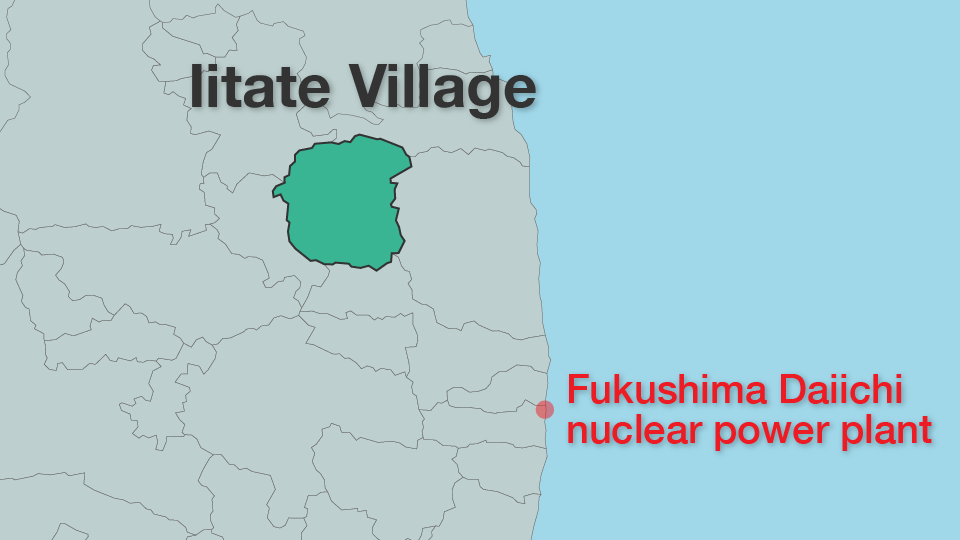

Iitate Village is 40 kilometers northwest of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. The entire town was contaminated by the radiation released during the accident.

The most beautiful village in Japan

Kanno ran a dairy farm in Iitate, his hometown, after graduating from university. In 1996, he was elected mayor. The village was never a wealthy place and the population was on a steady decline but Kanno worked hard to attract new residents and make life easier for those already there. He introduced incentives for people to move there and assistance for childrearing families. And to raise the village's profile, he promoted Iitate as a place blessed with natural splendor. Thanks to these efforts, a non-profit organization named Iitate one of "The Most Beautiful Villages in Japan" in 2010, the year before the nuclear accident.

Kanno describes his work building Iitate's reputation as "everything in my life". But the nuclear accident destroyed his efforts in an instant.

A month after the accident, Japan's government ordered all residents of Iitate to evacuate and proposed new locations for them to live outside of Fukushima. Kanno rejected these sites and arranged a shelter within an hour's drive of the village, inside the prefecture. He wanted to make sure everyone would be able to return home easily when things settled down.

He also persuaded the government to let residents of an elderly care facility stay in the village. This move led to the first significant criticism he faced as mayor, with some saying he was abandoning the elderly. But he argued that staying behind would be easier for them, both physically and psychologically.

Looking back, Kanno says he can understand where some of the criticism came from but insists that all his decisions were aimed at preventing Iitate from becoming a ghost town.

Criticism from residents

When the evacuation order for Iitate was lifted in 2017, Kanno decided to close all the temporary schools around evacuation sites and open new ones inside the village. He thought that children would return to the village if schools reopened.

But the decision was met with harsh criticism from parents worried about their children's health. Nonetheless, Kanno pressed ahead. After a one-year moratorium, families had two options: return to Iitate to join a new school, or switch to schools near their evacuation sites.

"Every parent had a different opinion," he says. "It was impossible to accommodate all of their requests. I think I made the right choice."

Iitate began bussing children to the village from their evacuation sites. In the end, about 70% of the students enrolled in the new Iitate schools.

Criticism from neighboring communities

Life was resuming in most of Iitate but an evacuation order remained in place for the district of Nagadoro, where radiation levels were relatively high. The central government said the order would be lifted only after more decontamination work had been carried out.

Kanno worked with the government to ensure these efforts went ahead. Most of the district is expected to be habitable again by the spring of 2023. But one small area is likely to still be too irradiated for residents to return. It was home to ten families before the accident, and Kanno was keen that they not be left out of Iitate's revival. He asked the central government to build a park in the area so they could at least visit, even if they could not yet move home. And he asked for the rules on entry before the area was fully decontaminated be relaxed for these residents.

This idea drew a sharp reaction from people in neighboring municipalities who argued that it would set a bad precedent.

Kanno says that it was a tough decision to make. "It's sad when you don't know what will happen to your hometown. I couldn't tell Nagadoro residents, 'Sorry, but you're just unlucky.'"

Navigating radiation differs from person to person

Kanno had to navigate many conflicting opinions as he worked to revive his community. "Everyone has a different view on radiation," he says. "They all believe what they think is right. It's extremely difficult to make decisions in such a situation."

But he says the only option is to share views and move forward. "There may not be a perfect solution. But we can aim for 60 or 70 points out of 100."

Nearly a decade since the nuclear accident, about 1,500 residents have returned to Iitate. But that's only 20% of the village's pre-disaster population, and the majority are elderly.

As Kanno stepped down from his post on October 26, after 24 years at the helm of his village, he shared one regret.

"I've been saying that empathizing with all residents is the most important thing in rebuilding the village. But looking back, I have to admit that I might not have done that enough."