On August 6th, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb for the first time in human history. Its target was Hiroshima, where 18-year-old Abe was helping to dismantle buildings to prevent the spread of fires caused by air raids during World War Two. Abe was working just 1.5 kilometers away from ground zero. She suffered severe burns on the right side of her body and face, and has been through 18 surgeries.

"The operations were very painful and difficult. There wasn't enough anesthetic back in those days, so doctors could not give me supplemental relief even if I started feeling pain. I tolerated the pain through a strong hope to restore my body," Abe recalls.

The bomb left keloid scars on her face and the right side of her body. In photographs from when she was younger, Abe always looks down, or shows only her left side.

A-bomb survivors call the 10-year period following the world's first atomic bombing "the blank decade." That is because people who were injured had little to no medical or financial support. At the same time, they were exposed to severe prejudice and discrimination.

Abe says she was once nicknamed "Red Ogre" because of her scars. "My wound did not heal. My body weakened. I was in poverty. Many people stared at me only just to satisfy their curiosity, because they wanted to know what a hibakusha looked like. They did not feel sympathy for me. They bullied me. The suffering that I went through, and the emotional wound, will never go away."

In 1956, Abe joined other atomic bomb survivors to form a delegation. They traveled to Tokyo to appeal to the then prime minister and government officials to offer relief for victims, and support their call for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Those efforts led to the establishment of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organization.

As the Cold War progressed, the hibakusha became disheartened. Even though they were speaking out about the need to eliminate nuclear weapons, the world was not listening. Nuclear experiments were being carried out repeatedly, and the arms race took off.

"It was really a difficult time for our campaign," Abe remembers. "We felt as if we were yelling out while trying to survive in rough waves on a dark night."

Abe carried a grudge against the US, but started to feel a change of heart almost 20 years after the bombing. In 1964, she went to the US and Europe for what was known as the Peace Pilgrimage. It was an opportunity for A-bomb survivors to speak about their personal experiences in front of audiences. Abe stayed at a private home with local hosts in the US, and she was deeply touched by their tender-heartedness.

"They listened attentively to my stories and said to me, 'It must have been very hard for you. You've been through a lot. We're so sorry for you,'" Abe recalls. "I realized we should never let anyone fall victim to nuclear weapons, regardless of what nationality you are. Americans or anybody."

The voices of the hibakusha spread to all corners of the world, slowly but steadily.

These days, the average age of hibakusha is more than 83 years old, and there are fewer chances to hear their direct accounts. Some of them, like Taniguchi Sumiteru, played a direct role in the recent ratification of the UN treaty that bans nuclear weapons.

Taniguchi died three years ago, but he put the wheels in motion with a campaign that collected signatures to demand an international convention to ban nuclear weapons. He worked on that until the last moment of his life.

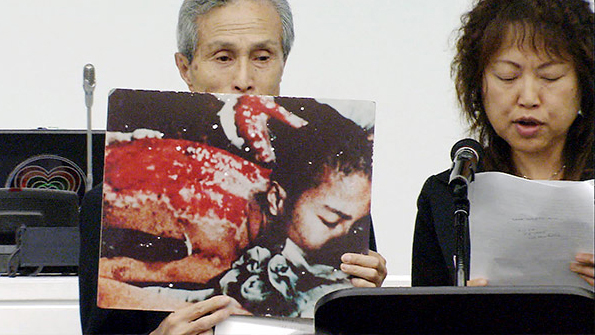

Taniguchi was 16 when he was exposed to the second atomic bomb that the US dropped on Japan. He was working as a postman in Nagasaki. A picture that shows the red burned flesh on his back shocked the world.

He delivered an impassioned speech at the 2010 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference at the UN's New York headquarters: "Please don't turn your eyes away from me. Please look at me again. I have survived miraculously, but for me, to 'live' was to 'endure the agony'. Bearing the cursed scars of the atomic bomb all over our bodies, we the hibakusha continue to live in pain."

"For humans to live as humans, not even one nuclear weapon should be allowed to exist on earth. I cannot die in peace until I witness the last nuclear warhead eliminated from this world," said Taniguchi.

Hibakusha and their supporters gathered at Nagasaki Peace Park shortly after last month's treaty ratification to share their joy. Among them was Okuma Yuka, a member of an activist group that calls itself "Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messengers".

Okuma took part in the signature-collecting campaign for the abolition of nuclear weapons after being deeply shocked by the image of a young Taniguchi in the aftermath of the atomic bombing. Her great-grandmother was a hibakusha but didn't talk much about her experience. The photograph of Taniguchi brought it home to Okuma that suffering had occurred in her own family.

"I believe the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is definitely an important step forward," Okuma says. "I expect that this will become a good opportunity for us to move toward a world that is completely free of nuclear weapons."