In Japan, where the Diet enacted an unprecedented extra budget of more than 57 trillion yen (roughly 540 billion dollars), the heavy spending is complicated by the government's already towering levels of public debt.

Adding to the challenge for the government is the latest round of requests for financial support from agencies and ministries. Together, they're asking for budget funding in the order of 105 trillion yen (about 1 trillion dollars) for the next fiscal year. That figure is likely to rise as the pandemic rolls on.

Financial crises of the sort confronting Japan and the rest of the world invariably revive the age-old debate over government spending. Deficit hawks urge restraint. They caution that governments can't afford to be profligate. Their opponents insist that austerity cripples economies, and that stimulus spending is the best way back to prosperity.

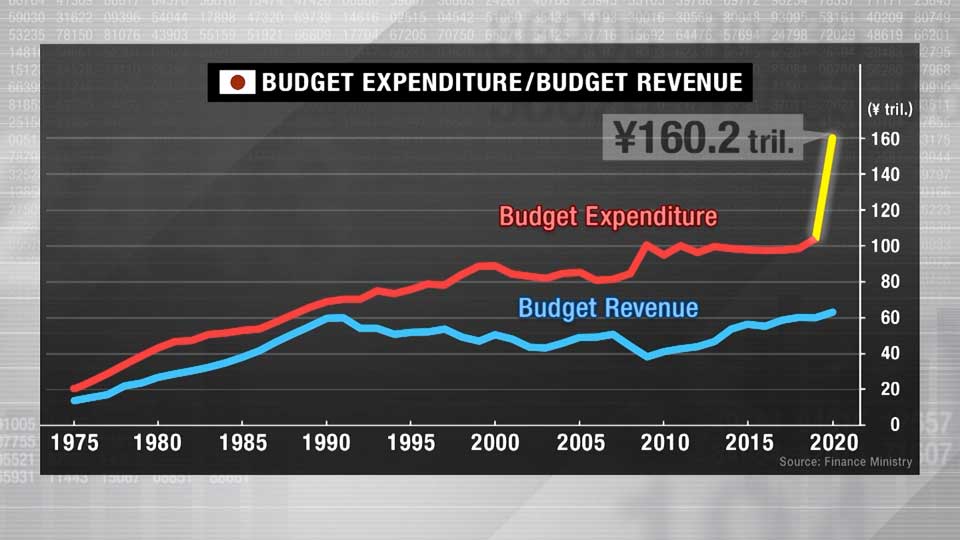

In Japan, this issue is brought into stark relief by a chart published by the Finance Ministry. The widening gap between spending and revenue is sometimes referred to in Japanese as a "crocodile mouth." In recent decades, several leaders have pledged to close it. None have succeeded. The onset of the pandemic has exacerbated the problem, prompting the government to pump out more bonds, and wrenching open the jaw with such force that it has dislocated entirely.

NHK spoke with major credit rating agencies to get their thoughts on the situation.

The pandemic hasn't affected the overall assessment of Moody's. But the US firm warns the crisis is threatening Japan on a number of fronts, including trade and investment, and expects efforts to contain the virus will continue to squeeze domestic demand.

Moody's points out that former prime minister Abe Shinzo left office before his economic platform, Abenomics, could come to fruition. The agency says it appears increasingly unlikely that Japan can achieve its twin goals of 2% inflation and eliminating the deficit by 2025.

Another US agency, S&P Global Ratings, announced in June that it would lower its outlook for Japan's sovereign rating from positive to stable. While that doesn't entail a downgrade of government bonds, the agency had made it clear that it feels Japan is falling behind in its quest to achieve fiscal stability, largely because its finances are expected to worsen as the government tries to spend its way back to economic growth.

In July, Fitch Ratings cited the impact of the pandemic as it lowered its outlook for Japan's credit rating from stable to negative. Stephen Schwartz, who heads the agency's Asia Pacific Sovereign Ratings, notes that even before the global crisis, Japan's debt-to-GDP ratio was far and away the highest of any country. He estimates it will shoot up from 230% to 260% over the next one to two years, increasing the medium-term challenge of gradually reducing the debt after the crisis passes.

But he stresses that fiscal expansion under the current circumstances is the right approach, and that the increasing deficit is not the reason behind the rating downgrade. Rather, Fitch looks to measure a country's prospects for medium-term growth through structural reform. And he says this will be a big challenge for Japan given its aging population.