It’s estimated there are 136,700 survivors left in Japan. Known as hibakusha, many were infants or unborn when the United States dropped the bombs in 1945. They heard stories of the time from older family members who are now deceased.

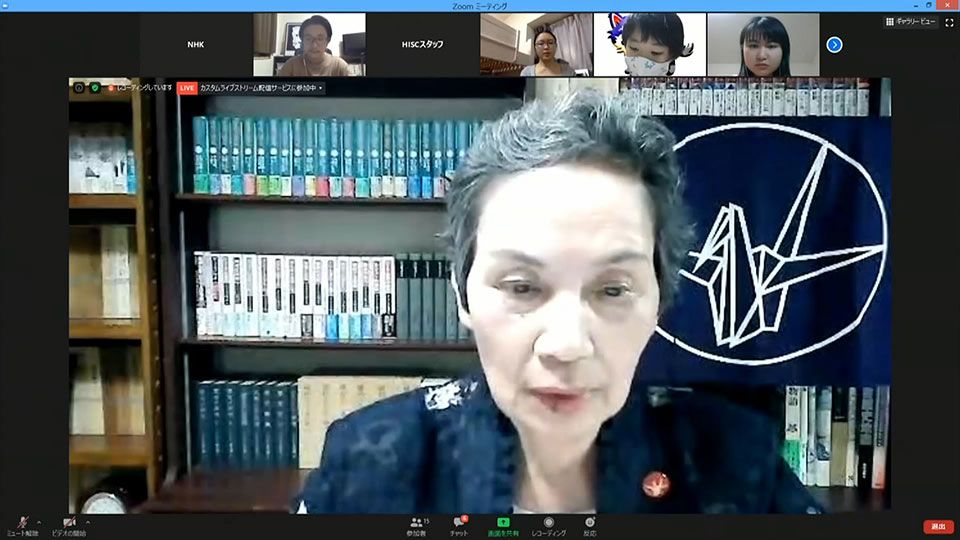

“I’m very afraid of imagining a world where hibakusha, who can talk about their experiences, are gone,” says 76-year-old Nagasaki survivor Wada Masako. “Every time I think about losing them, I feel like crying because I’m so scared.”

Sharing the nuclear experience

Wada was only one year old when she was exposed to radiation 2.9 kilometers from the epicenter of the blast. She was playing alone by the entrance to her home, while her mother was preparing lunch in the kitchen. This is all according to her mother, since she was too young to remember anything about what happened on August 9, 1945.

Although Wada doesn’t have the memory herself, she is a leading figure for denuclearization among the hibakusha and has given testimonies at international forums, including a 2017 conference in Vatican City. She speaks about what her late mother witnessed and experienced.

“People picked up dead bodies lying on the streets, and threw them into garbage trucks, making a pile of corpses. Their legs and arms were hideously burned. They looked like dolls. Day after day, those bodies were burned in an empty lot next to my house. My mother said everyone soon became numb to the growing number of corpses and the smell of the burning bodies.”

Wada has been sharing her mother’s experience with others since 1984, but has always struggled with whether she is really entitled to speak as a hibakusha.

“I dictated what my mother witnessed and showed it to her before she died. She seemed quite dissatisfied when she read it. I think she felt that no words or expressions could describe the hell she had really gone through. And I’m sure other senior hibakusha feel the same way as she did…. So I have always felt hesitant to share my mother’s experience and I still am.”

But as the number of hibakusha with first-hand memories of the attack shrinks, Wada thinks it’s important for the younger ones to take up the mantle.

“For now, we young hibakusha must step up to the senior hibakusha’s work and speak on their behalf. However, in decades to come, I want the young generations to take over. Of course they don’t have the memory of the tragedy, but neither do I. I want youngsters to listen to the hibakusha while they can and pass on the memories. Exactly what they were told, like what I’ve been doing for the past 30 years.”

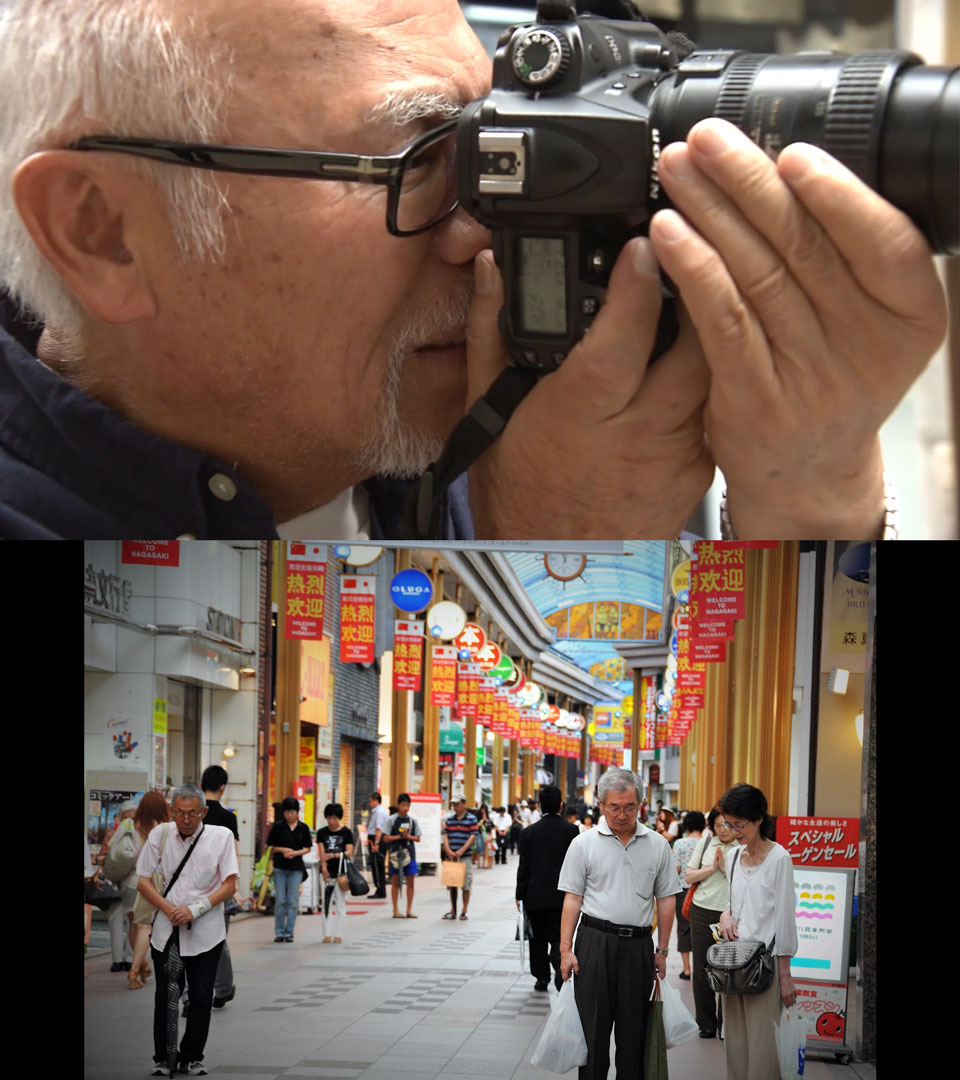

Photographic project a reminder of what was lost

Another Nagasaki survivor, Ogawa Tadayoshi, 76, has turned to his hobby of photography to maintain the hibakusha spirit. He had evacuated to the countryside at the time of the bombing but returned to the city with his family a week later and was exposed to radiation.

“I don’t remember anything,” Ogawa says. “What I know from my parents is that our house had been destroyed, nothing left. I later asked them what the city was like at the time, but they never really explained it to me. I had a sense that my family were trying to forget about what they’d seen.”

Ogawa was not particularly active in the hibakusha community until 2009, when he started a project asking people to take photographs at 11:02 a.m. every August 9, the exact time the bomb was dropped. He was worried that the memory of the tragedy was fading, even in Nagasaki.

“In Nagasaki, people offer a moment of silence every year at the time of the bombing, but I was very shocked to see many people weren’t paying any attention,” Ogawa says. “I wanted to play a role as a hibakusha even though I didn’t have the memory. So I decided to use one of my hobbies in order to keep the memory of the bombing alive.”

Twelve years on, his project has garnered attention across the country. Last year, more than 110 pictures were sent from Japan, and for the first time, Ogawa received snapshots of the moment from abroad.

“By taking a picture of what you like, I want people to realize those things would have been taken away in Nagasaki 75 years ago and remember the tragedy,” Ogawa says. He hopes to involve more young people both inside and outside of Japan. “I believe that a single step by 100 people is more important than 100 steps by a single individual.”

In the near future it won’t be possible to hear first-hand testimonies of the atomic bombings. But the youngest hibakusha have become bridges between those who witnessed the tragedy and those who are still learning about what happened.