In mid-August, Dewa Hitoshi visited a schoolhouse in the mountains of Kanagawa Prefecture, west of Tokyo. Dewa made the trip to honor his father who had been interned there during the war, labeled an enemy of Japan.

"It's deeply moving for me to be standing in the place where he was interned," Dewa said with emotion. "Surely he also gazed upon these same mountains."

Dewa's father, Sydengham "Syd" Duer, was a British citizen born in Japan to a Japanese mother and British father. He was 22 when the war broke out and studying to become a physician. But his dreams were put on hold as he and his father were sent to an internment camp where they were held for nearly four years.

They were among 53 non-Japanese civilians who were detained in the camp for the simple reason that they held passports of Allied nations.

Japan began its internment policy at the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941. There were 34 detention centers initially, to house men aged 18 through 45. Eventually women and the elderly were also sent to camps around the country.

In total, about 1,200 people are estimated to have been detained. 50 are said to have died in the camps.

The government claimed the program was aimed at preventing espionage, and designed to protect the internees.

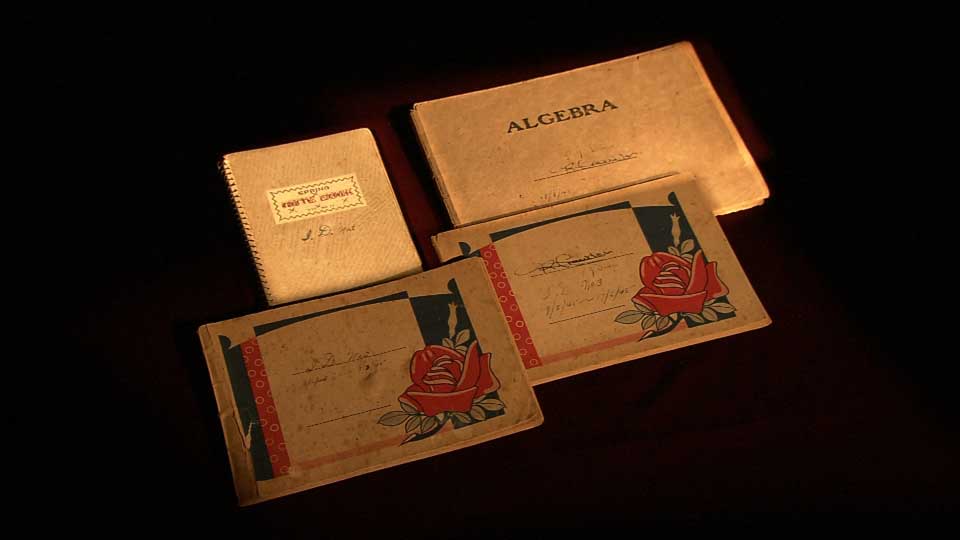

During his time at the camp, Syd kept a diary—written in both Japanese and English—that spans four volumes.

"What a narrow-minded country Japan is! Aren't they ashamed of interning students, such as myself, and the elderly, the 70-year-olds?"

Syd was raised in Yokohama, a port city that had been home to a vibrant foreign community since the mid-19th century. His father, William, was a diamond importer. The family enjoyed a prosperous, happy life—brought to an abrupt end with William and Syd's internment.

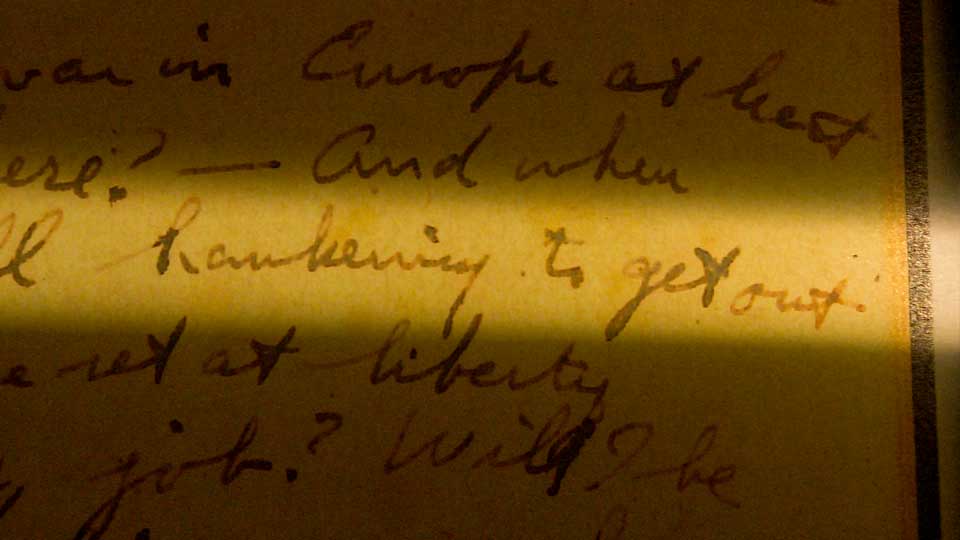

"We are all hankering to get out of this life of restrictions, but when we are set at liberty, what then?"

Life at the camp was unforgiving. Food was scarce and there was no heating. Temperatures during the winters dipped below freezing. By the end of the war, five of the 53 internees had died.

Komiya Mayumi of POW Research Network Japan has studied the internment program extensively. She says the conditions at Syd's camp were particularly bad.

"The fact that five people died shows the camp didn't do anything to protect the internees," she says. "They weren't cared for, they weren't fed enough and they became malnourished. Basically, they were left to die."

Syd's diaries include accounts of his treatment, detailing the hard labor and how the guards would take the internees' rations.

"Worked half day in the hills, and we received two tiny sweet potatoes," he wrote. "They are saving thousands of yen due to our free labor, and won't even feed us properly after all the work—the days of slavery are not gone yet."

Behind the schoolhouse, there is a simple tombstone engraved with the names of the two internees who had no one to retrieve their remains. It was left to Syd to dig their graves.

"He had no medical attention," Syd wrote. "They just let him die like a dog. Last year we dug Emery's grave and we'll bury Jonah next to him.

"May his soul rest in peace."

Throughout the journals, Syd writes with brutal honesty about the complex emotions he has for the country he calls home.

"Japan treats me as an enemy, but as for me, I love Japan. It is true it's the Japanese that have interned me and have brought upon me such misery, but such Japanese are really but a handful. They are traitors to their own country in patriots' clothing."

Syd and William made it out of the camp alive. After the war, Syd resumed his studies, became a doctor, and finally obtained citizenship in 1973. He died in 1990 at the age of 70.

One line in the diaries explains why Dewa still visits the school all these years later:

"When considering differences in nationality, race, and culture, there are enormous lessons to be learned from war."

While the stories of internment camps in the United States have been told, even the existence of the Japanese equivalents is little known.

Dewa wants to change that, and says he is now thinking about publishing the diaries that have, until now, been kept within the family.

"I believe that my father's diary is important to share as one aspect of war."